Historical analogies can be very useful at times. There is an excellent replay happening in iron ore that is one of them.

The last time China undertook a great structural reform was with the ascension of Xi Jinping in 2012. At that time, it suddenly began to become de regeur to discuss Chinese “rebalancing”

In effect, this meant a shift away from building apartments to creating activity for consumption.

The shift topped out Chinese steel and seaborne iron ore prices from the moment it began.

It lasted for five years, punctuation by fits and starts of stimulus before bottoming out in late 2015 with the introduction of Chinese QE for property developers.

This final panic reversal to the old economic model of building empty apartments blew off Chinese steel output for another six years. It rescued Chinese steel prices and helped iron ore supply to work off its excesses.

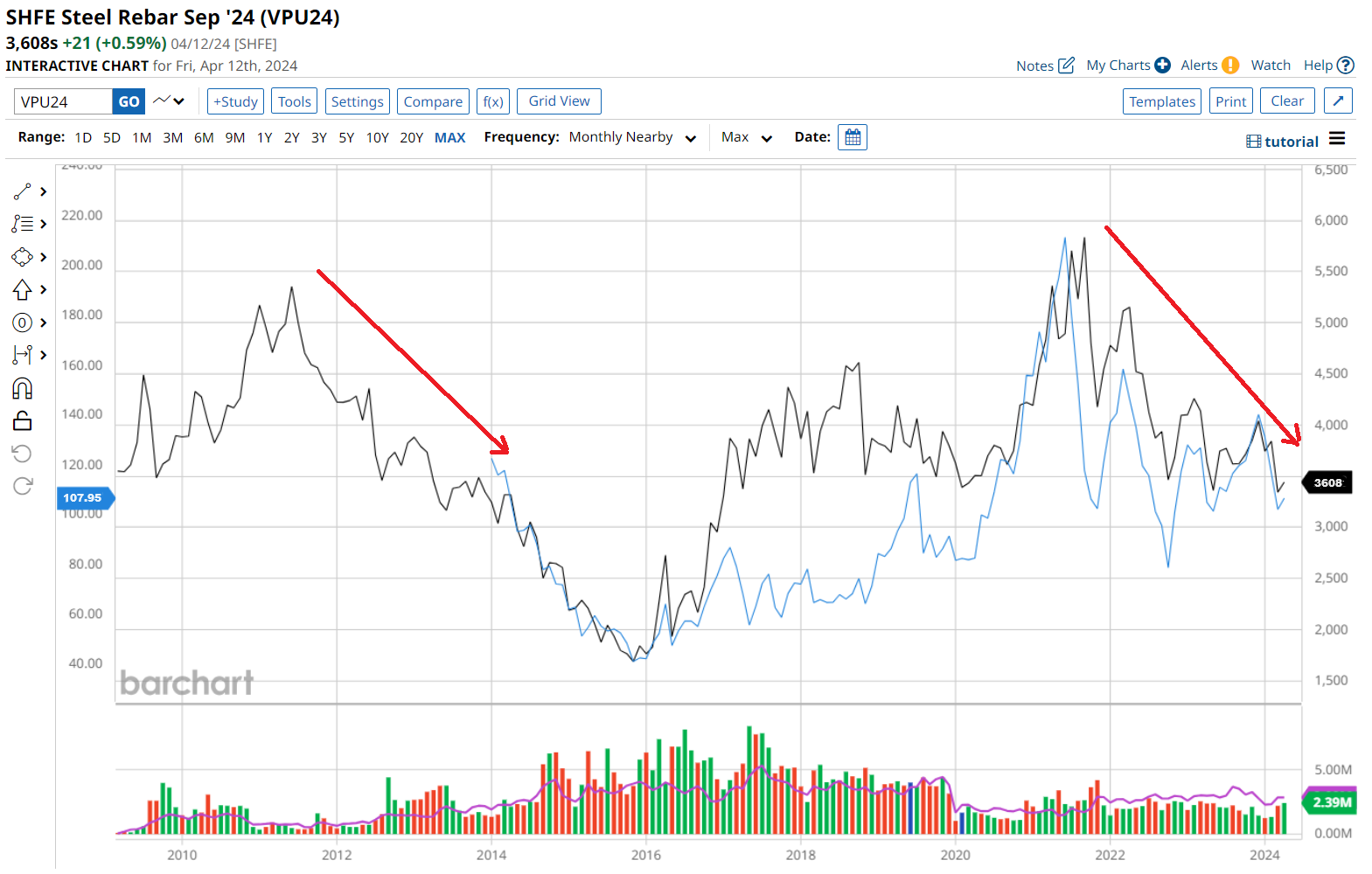

The chart below shows this all very clearly: black is rebar, blue is SGX iron ore (there is no data prior to 2014 for the latter):

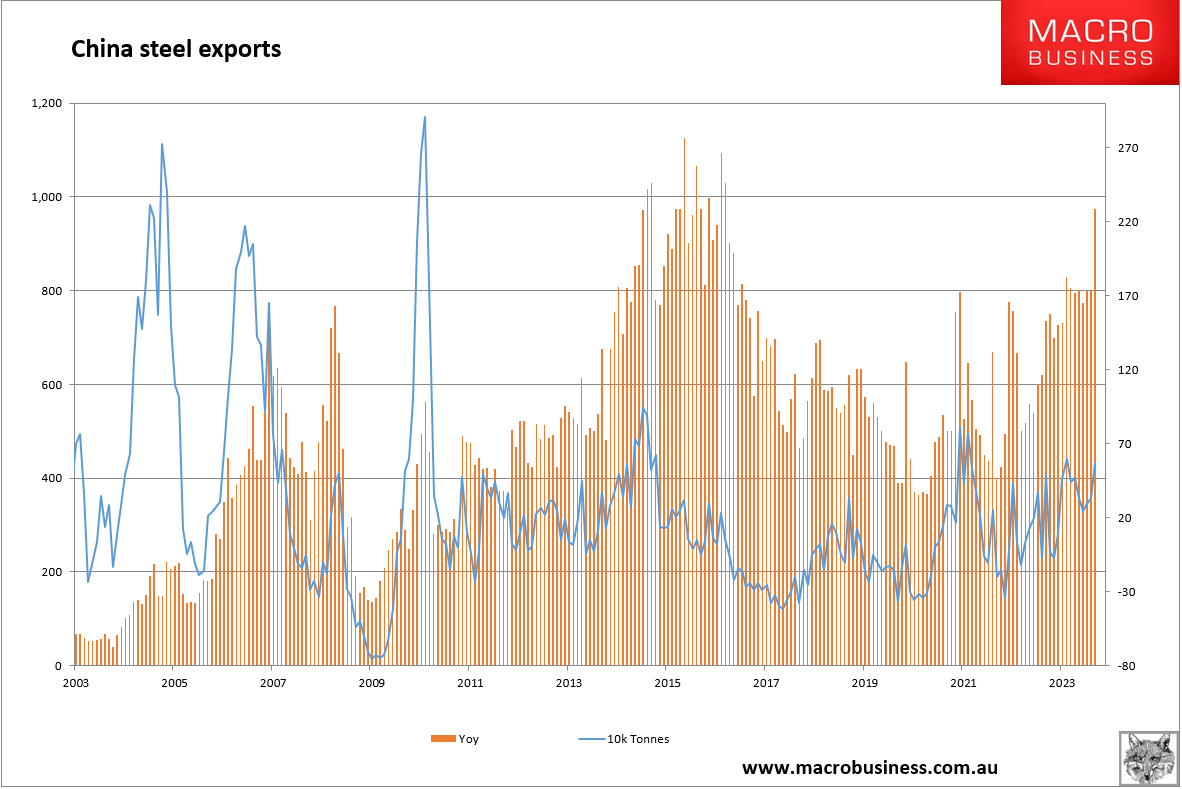

The mirror image of these patterns is to be found in Chinese steel exports, which boom when local prices tumble and become very export competitive. In the years 2012–2016, exports went nuts as steel prices kept falling:

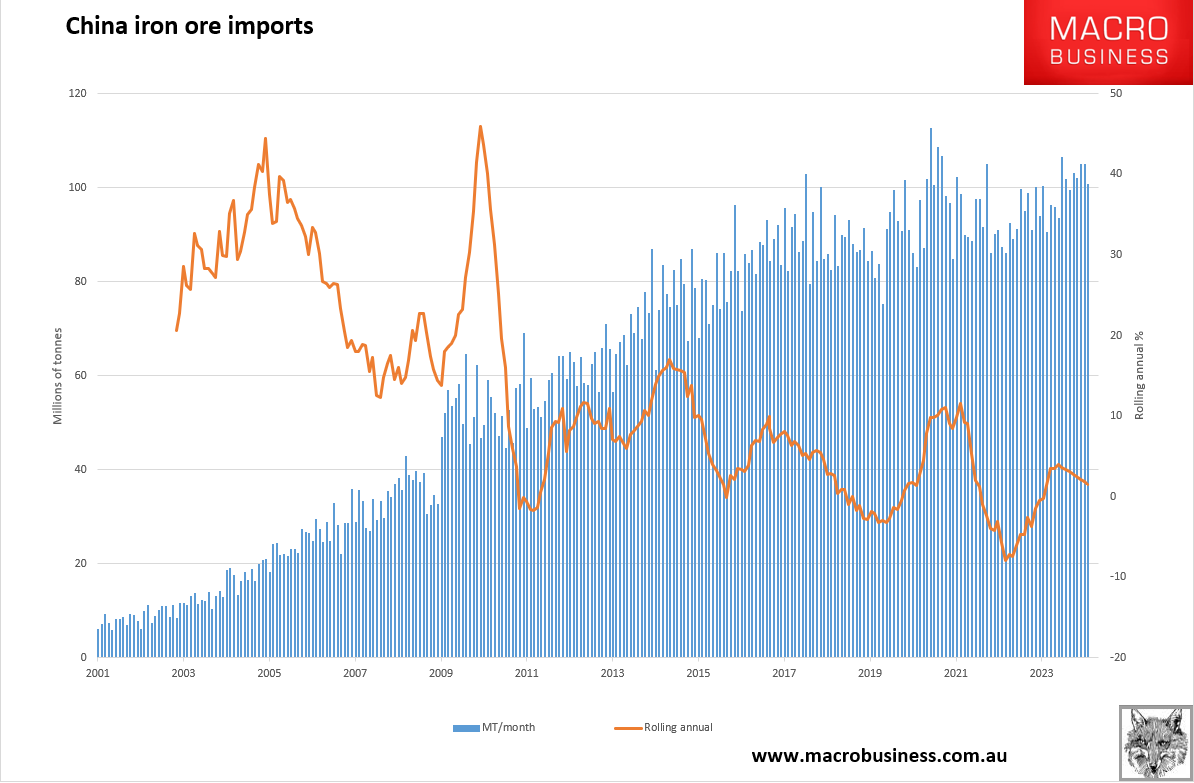

Iron ore imports show a different pattern because the crashing iron ore price was doing the same to China in reverse, as its high-cost production was replaced with imports:

With these charts, I want to show that, contrary to popular belief, rising Chinese steel exports (which just boomed again in March) are a terrible sign for the strength of the global FE market.

They transpire when Chinese demand conditions are so weak that steel prices fall and the surplus is dumped globally. Iron ore and coking coal follow the lower prices of steel.

And neither stops until something makes them stop.

In 2016, that was Chinese QE and the rationalisation of its glutted steel sector.

Shifting to the present, such measures are underway again in China. There is QE for developers and shanty town development, massive quotas for infrastructure spending and special bonds galore.

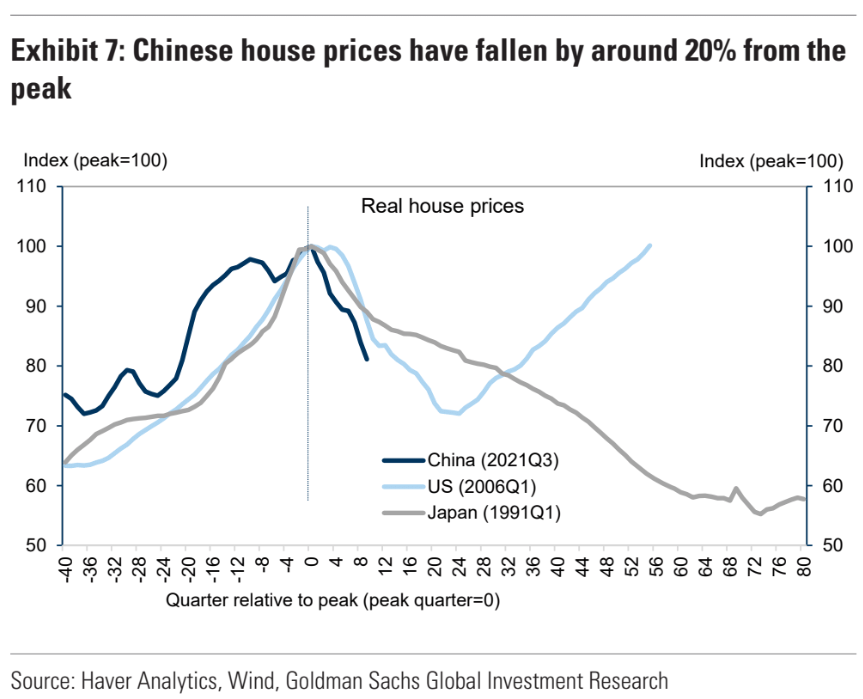

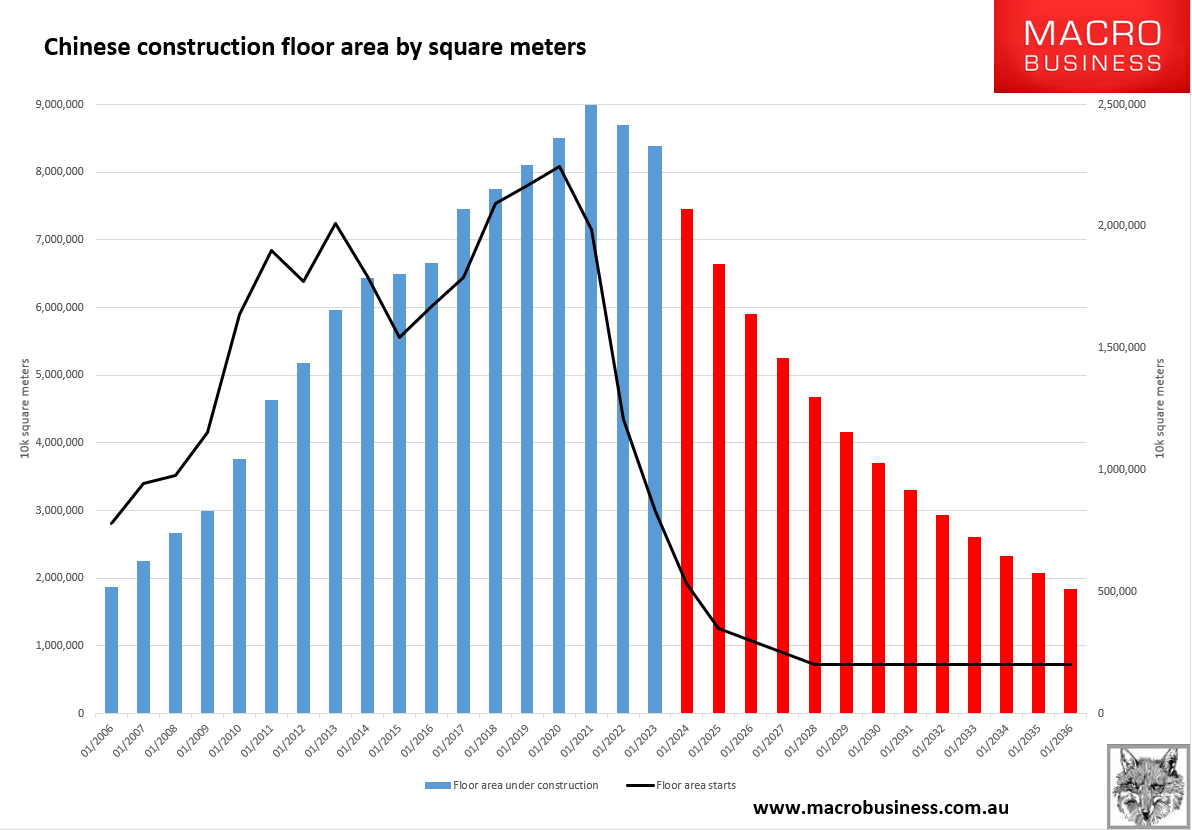

The problem is the last great 2016-2021 blowoff so bloated developer credit, corruption, and over-construction that today’s property crash is past saving:

And steel demand in China is going to shrink every year for the next decade (or crash faster):

Indeed, today’s stimulus measures are designed to slow the decline of construction volumes, not reverse them.

For the Chinese steel market this means just one thing. A superglut is mounting in China and will crash upon every global shore in a relentless tide over the next five years.

For that to happen, the steel price will have to keep falling in a rerun of the 2012-2015 crash. All things equal, iron ore plus coking coal will go down with it.

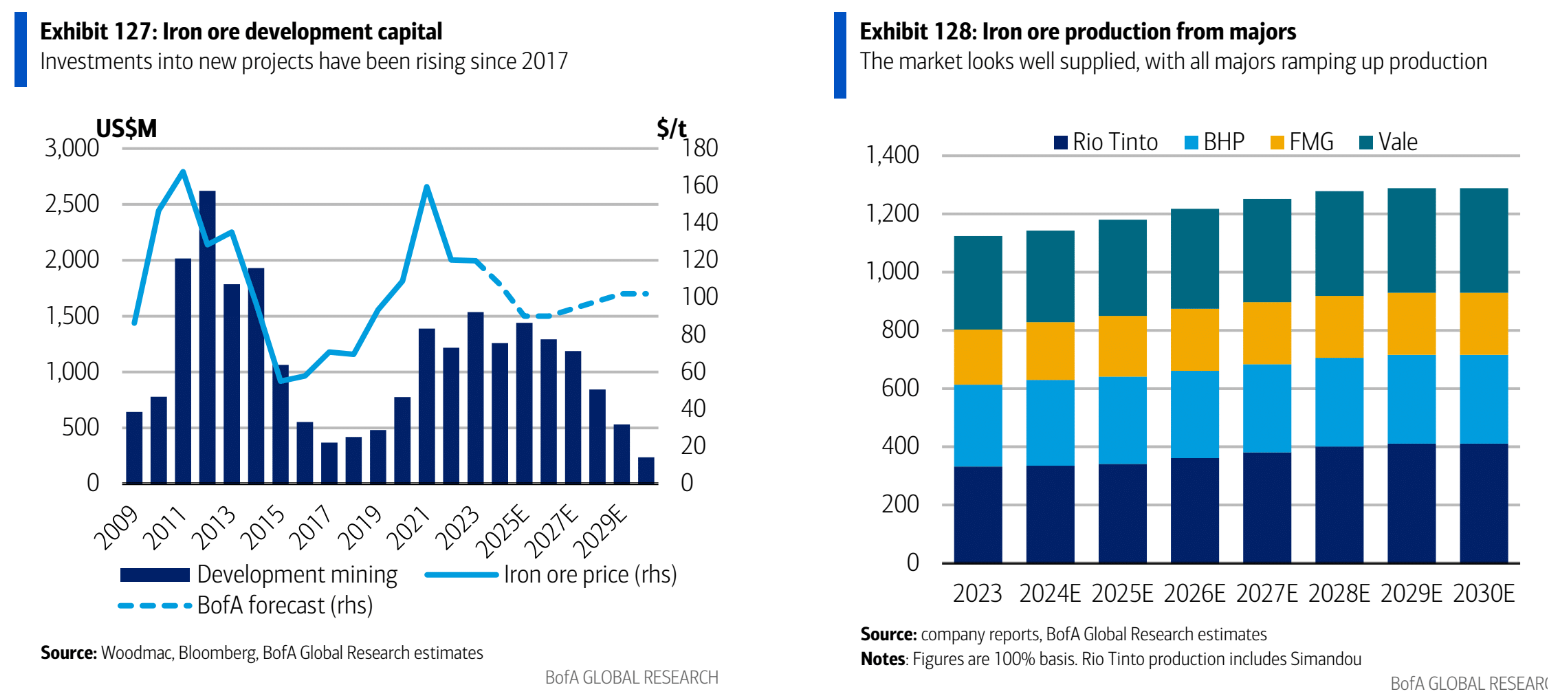

And there is one further factor to add on the supply side for iron ore. The 2012 Xi Jinping pivot caught big mining with its pants down, as it invested heavily in the notion that China would grow apartments forever.

They were wrong, and their excess supply weighed on the market even more as Xi’s pivot sucked away demand.

This is why iron ore underperformed the post-2015 steel rebound until a Brazil accident took 100mt offline in 2018.

Well, they have done it again:

Nearly 160mt of new iron ore is headed for global market from next year through 2028.

Just as the great Chinese property adjustment sucks away about the same in iron ore demand.

Iron ore is going to have to shake 300mt of supply as we rerun 2012–2016 to the letter from 2022-2026:

Only this time, there will be nothing to rescue it when it is done.