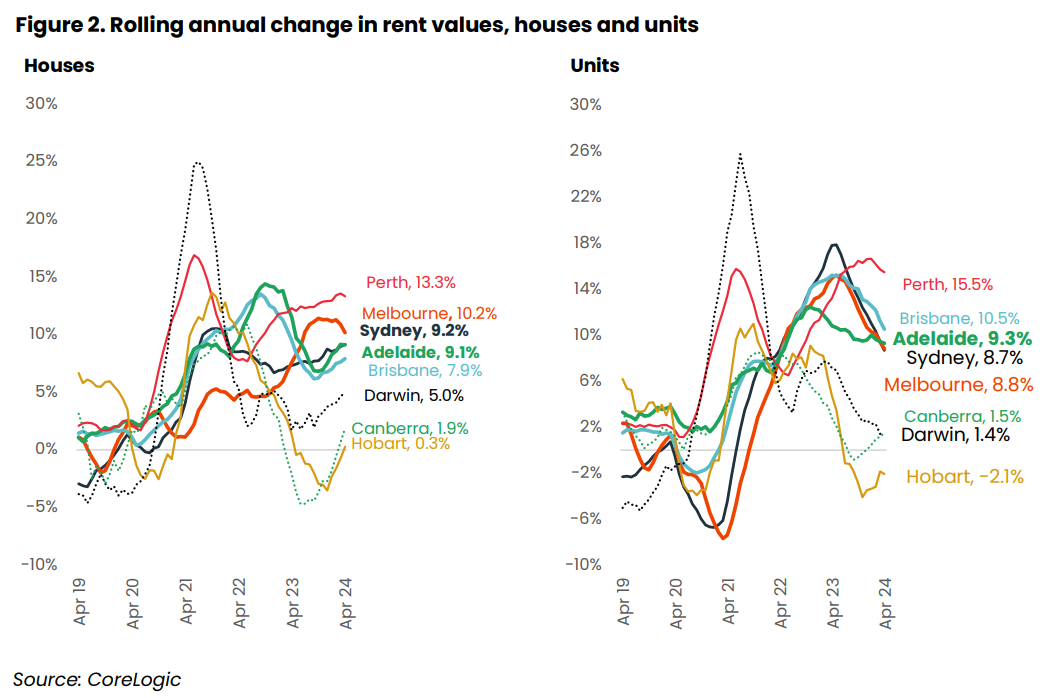

The latest data from CoreLogic shows that Australian rents continue to rise at a swift pace, led by the largest capital city markets.

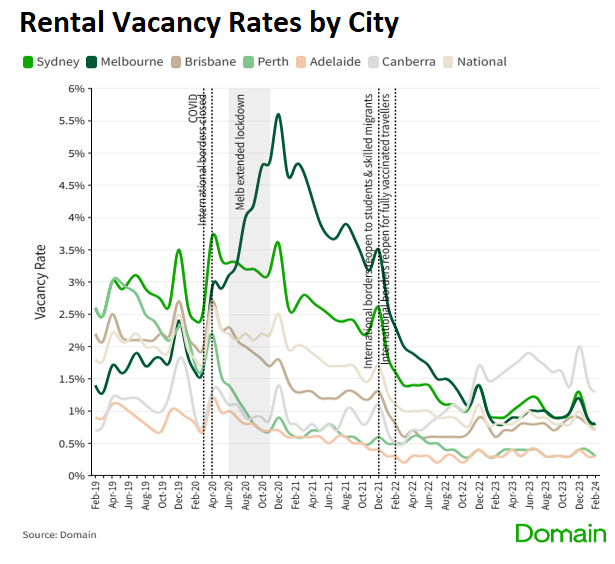

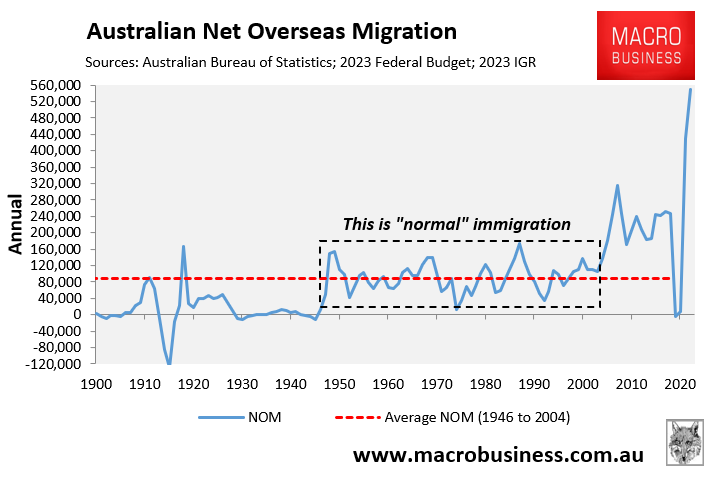

This increase in rents has occurred amid a steep fall in rental vacancy rates following record net overseas migration.

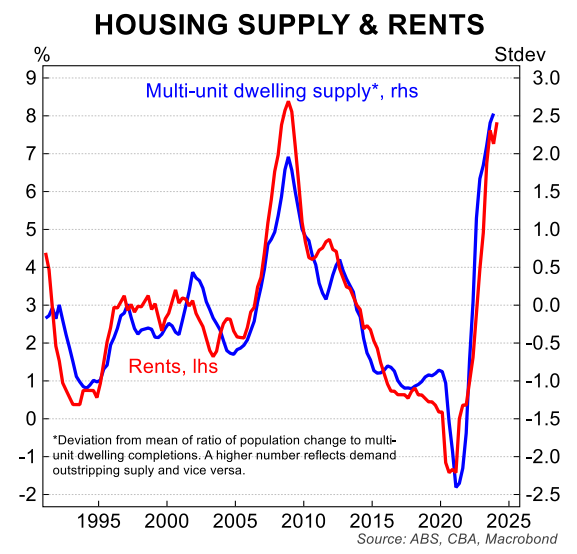

According to CBA research, Australia’s rental inflation is directly proportional to the ratio of population growth to apartment building.

Therefore, rental inflation will rise when either population increases or apartment construction decreases, other things being equal.

Both trends have occurred at the same time over the last two years, resulting in surging rents.

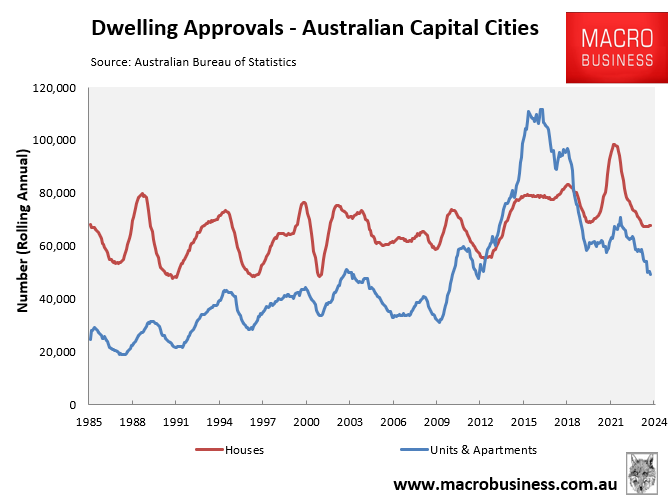

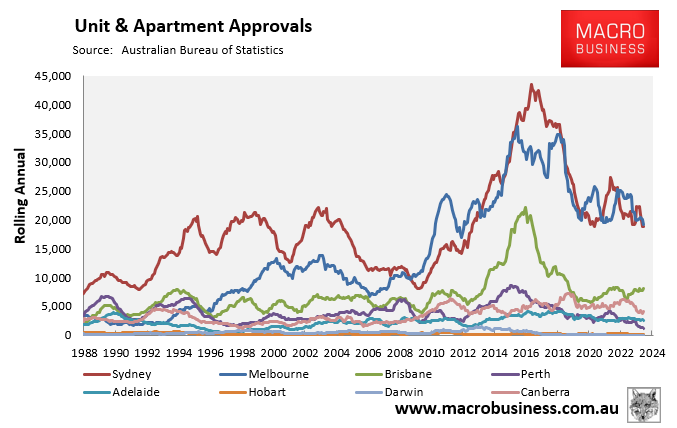

The latest Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) dwelling approvals data exacerbated the agony felt by renters.

Annual apartment approvals in the combined capital cities fell to their lowest level since April 2012, with only 49,448 units permitted for building in the year to March.

As seen above, the number of apartment permits in March 2024 was less than half of the 111,667 approvals recorded in the year to September 2016.

Furthermore, the decline in apartment approvals was concentrated in the three largest capital cities—Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane.

Tim Reardon, Chief Economist for the Housing Industry Association, issued a warning about the situation.

“The mismatch between rising demand from migration and constraints on the supply of housing is likely to see the acute shortage of housing stock continue to deteriorate”, Reardon said.

“This lack of new work entering the construction pipeline is occurring alongside record inflows of overseas migrants and a pre-existing acute shortage of rental accommodation across the country”.

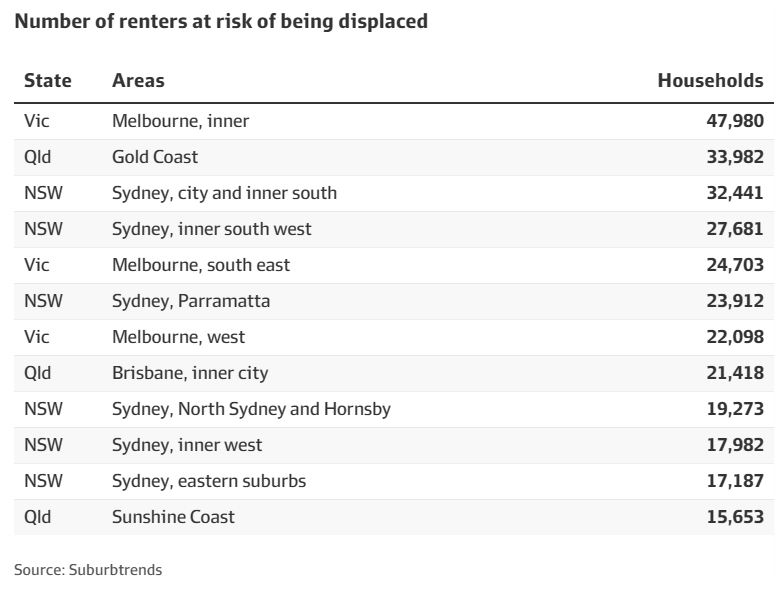

The impact of the rental shortage will be most severe for Australians on lower incomes.

Suburbtrends director Kent Lardner released analysis showing that more than 800,000 households that rent their home could potentially be displaced.

“The mounting pressure from the relentless increases in rents are prompting wealthier households to seek out cheaper rental homes, crowding out those in the lower socio-economic ladder”, Lardner said.

“The intense competition for a limited pool of rental properties and a dire shortage of affordable housing options mean this problem will ripple out to the poorest suburbs, leaving those in the lowest socio-economic households under the most strain over the medium to long term”.

Already we have witnessed a sharp rise in homelessness, with tent encampments popping up across the nation.

Australians are also being forced to rely on charities for food.

The latest annual survey from the nation’s largest food rescue organisation, OzHarvest, showed that the need for food relief has reached record new heights, and two-thirds of the charities tasked with providing assistance are being forced to turn hungry people away.

“We’re delivering over half a million meals across the country every week, but it’s just not enough”, OzHarvest founder Ronni Kahn said.

“(The charities) say they’re doing their best to feed everyone but are often faced with turning people away as they just don’t have the food”.

“We’re delivering over half a million meals across the country every week, but it’s just not enough”.

“(The charities) say they’re doing their best to feed everyone but are often faced with turning people away as they just don’t have the food”.

“The vast majority could take up to double to meet demand”, Kahn said.

Increasingly, families with two working parents are seeking assistance, according to Kahn.

“It’s heartbreaking to think that it’s easier for parents to keep kids home from school when they can’t afford food for lunchboxes”, he said.

Three-quarters of the charities polled said that demand for food has increased in the last year, with nearly one-third (30%) of those seeking assistance doing so for the first time.

Last year, 47% of charities struggled to meet demand due to increased food prices and interest rates. That proportion has now risen to 67%.

OzHarvest believes that at least 30,000 Australians go hungry each month, but thousands more are unlikely to seek assistance.

So long as the federal government continues to run an oversized immigration program in a supply-constrained market, Australia’s rental crisis will worsen.

More lower-income households will be forced to live in group housing, become homeless, or will suffer severe financial strain.

The solution is to cut net overseas migration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, the situation facing renters and families will continue to deteriorate.