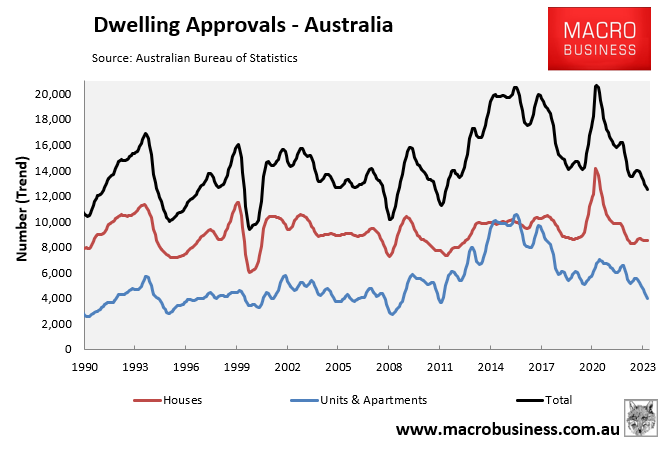

Last week, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released dwelling approvals data, which revealed that only 12,500 homes were approved for construction over the month of March in trend terms, which was the worst monthly result since April 2012.

The result was nearly 40% below the Albanese government’s housing target, which requires 20,000 homes to be built a month to hit its goal of building 1.2 million homes over five years.

On that monthly run rate, Australia would build only 150,000 homes a year, which is 90,000 below the Albanese government’s target of 240,000 homes a year.

The number of loans issued for the construction or purchase of new homes also remained near all-time lows in March:

This means the last 20 months of new home lending has been weaker than any equivalent period since the ABS started this data series in 2002.

On Friday, the National Housing Supply and Affordability Council (NHSAC) released its first State of the Housing System report, which found a “significant shortfall in supply” that will result in housing affordability further deteriorating over the next six years.

Chair Susan Lloyd-Hurwitz put it bluntly: “Prices and rents are growing faster than wages, rental vacancies are near all-time lows, 169,000 households are on public housing waiting lists, 122,000 people are experiencing homelessness and projected housing supply is very low”.

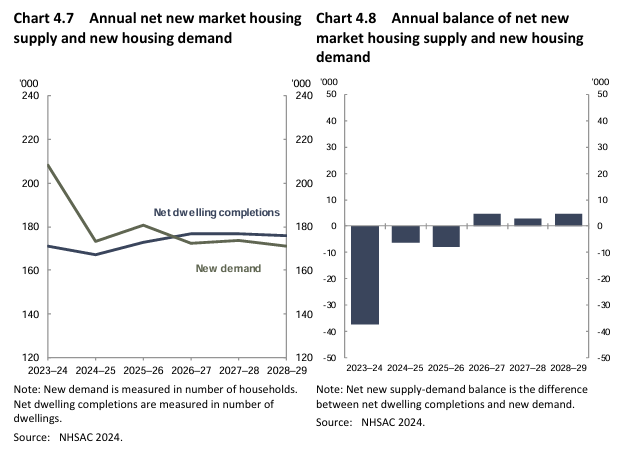

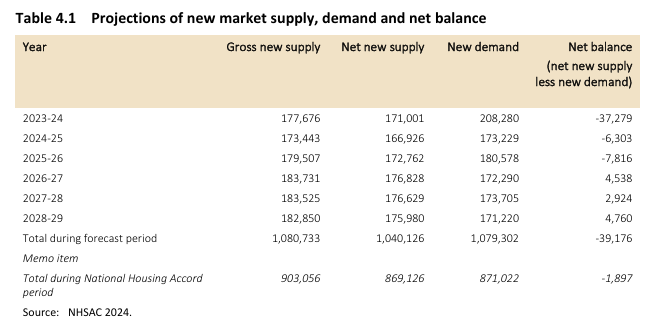

According to NHSAC’s projections, there will be a considerable shortfall in new housing supply compared to new demand of around 37,000 dwellings in the financial year 2023-24.

After subtracting demolitions, the market is expected to supply only 1,040,000 houses over the Council’s six-year projection period.

New demand is expected to total 1,079,000 households. This equates to a total shortage of around 39,000 houses in new market supply relative to new demand over the next six years.

These deficiencies in new supply relative to new demand will exacerbate the system’s already considerable housing undersupply. As a result, housing affordability is expected to decrease further over the projection period.

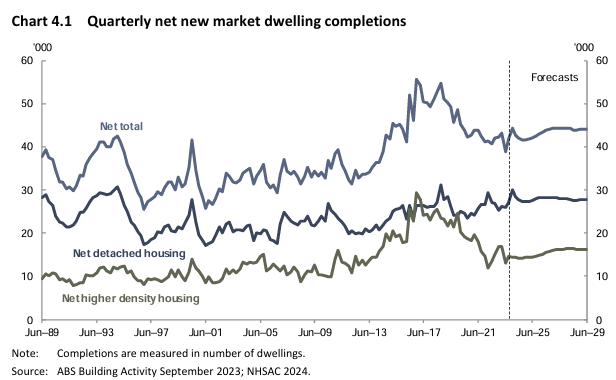

From 2025, supply is projected to increase as rises in rents and dwelling prices and a slowing in the growth rate of construction costs (Chart 4.2) induce developers to add to the dwelling stock.

NHSAC anticipates that a projected decrease in mortgage rates (Chart 4.3) will further support this supply increase, though higher unemployment and a slowdown in household income growth will partially offset it.

NHSAC projects that over time, this additional supply, coupled with slowing new demand due to lower population growth, will bring new supply and new demand closer into balance.

In turn, this will slow the rate of growth in housing prices and rents.

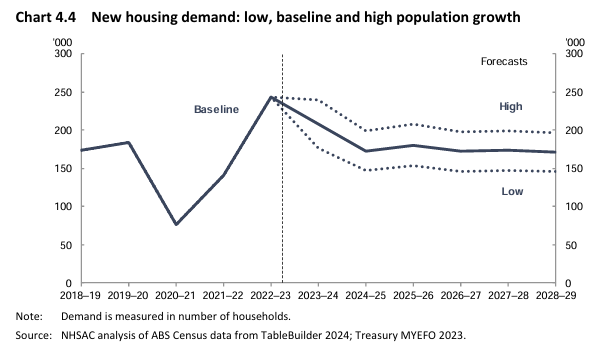

NHSAC anticipates that there will continue to be a high level of housing demand in 2023–2024, with the formation of 208,000 households. From 2024–25, underlying demand is forecast to stabilise at around 174,000 new households formed per year (Chart 4.4).

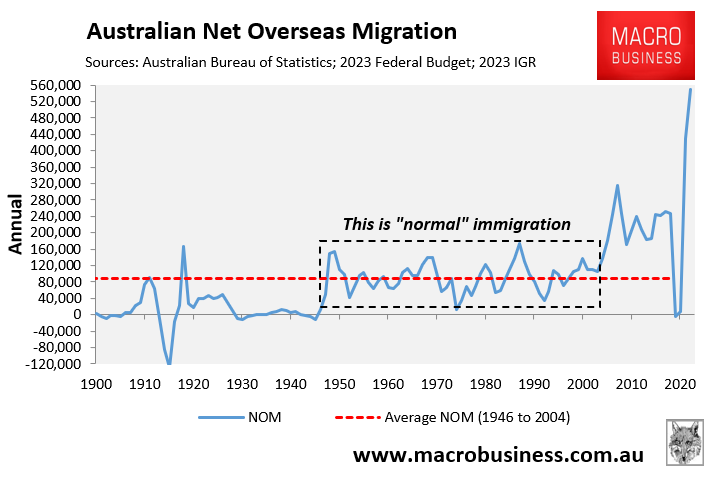

The elevated household formation rate in 2023–24 largely reflects strong population growth from record net overseas migration.

However, population growth is forecast to return to pre-pandemic levels from the 2024–25 financial year.

The NHSAC’s baseline projections imply that new demand for housing will exceed new market supply in the 2023–24 financial year, as it did in 2022–23, but that the maximum extent of this imbalance has passed and is in the process of normalising (Chart 4.7).

In the 2024–25 and 2025–26 financial years, new demand for housing will moderately exceed new market supply.

Then new supply and new demand will be roughly in balance from the 2026–27 financial year onwards, according to NHSAC.

Over the full NHSAC six-year projection horizon, net new market housing supply is expected to total 1,040,000 dwellings whereas new demand is expected to total 1,079,000 households.

This represents a deficit of new market supply relative to new demand of around 39,000 dwellings over the six-year period (Chart 4.8).

NHSAC warns that these shortfalls in new supply relative to new demand will add to the already significant undersupply of housing in the system in the absence of a significant change in housing policy or the capacity of the housing sector to supply new dwellings (Table 4.1).

As a result, housing affordability is expected to deteriorate further over the forecast horizon.

There will be no surplus of new housing supply to address the significant unmet demand for housing that currently exists due to affordability constraints or to accommodate the 122,000 Australians experiencing homelessness at the time of the 2021 Census.

NHSAC warns that for those looking to acquire their first home or upgrade to a more expensive dwelling, the cost of doing so will remain high.

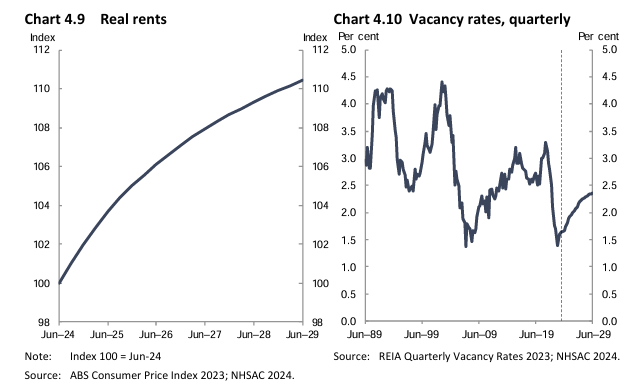

For tenants, rental costs will continue to exceed rises in the broader cost of living (Chart 4.9).

Rental housing will remain scarce, with the vacancy rate projected to remain below that consistent with a stable rental market (Chart 4.10).

NSAC warns that Australia’s high costs of housing will continue to impact the wellbeing of the most vulnerable in the community, who are the least able to manage elevated housing costs and access scarce rental accommodation.

“It will add to incidences of overcrowding and homelessness, and limit economic and social inclusion” the report says.

Hilariously, this report is the polar opposite of the National Housing Finance & Investment Corporation’s (NHFIC) flagship report on housing supply and demand, which was released in late 2020 when net overseas migration collapsed during the pandemic.

NHFIC forecast that “cumulative new supply is expected to be around 93,000 higher than new demand by 2025”, thanks to the fall in immigration (see next chart).

Additionally, NHFIC predicted that the migrant epicenters of Greater Sydney and Greater Melbourne would experience the biggest surpluses in housing supply:

Clearly, the biggest driver of Australia’s housing shortage is net overseas migration.

The solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to slash net overseas migration to a level that is well below the nation’s ability to build new homes and infrastructure.

Otherwise, Australia will experience a permanent housing shortage.