Immigration influencer Abul Rizvi is among the critics of the federal government’s plans to impose a cap on the number of new international students, which is supported by the Opposition.

Rizvi believes that the cap is intended as a “stop-gap measure” in response to high net migration levels and low housing supply and has described the measures as a “recipe for chaos”.

“It’s quite extraordinary [policy] and all about getting to the 2025 election”, he said. “The levels of intervention exceed anything I’ve ever seen in any other industry. This gives them the power to tell a business how many customers you can have, what they can buy from you and how much”.

“The power and its use is unsustainable. You can’t run an industry this way”.

Rizvi has also warned that some universities could potentially be forced to close if the policy is managed poorly, while admitting that the current student visa system has been rorted:

“They’re going to have to start cost cutting”, he said.

“They’ve designed the system not in terms of academic excellence, but revenue generation”.

“A better policy would be to place a higher cut off score on entrance exams so universities don’t put forward students with poor scores. You’d still control the numbers by letting them compete”.

Professor Andrew Norton from the Australian National University also claims that the proposed legislation includes an unprecedented level of ministerial discretion to enforce the caps.

“The level of ministerial discretion is unprecedented … the powers are there [and] the mere possibility of their use changes the government-university relationship”, Norton wrote.

“With the government and opposition united against international students we have to accept that provider caps will happen. But course level caps … are in fundamental conflict with principles of student choice and university autonomy”.

The AFR’s Jennifer Hewett provided a more honest take, noting that many local students have been forced into classes with large numbers of foreign students, degrading their experiences:

“The universities’ arguments for greater nuance in limiting numbers are undermined by their willingness to allow some courses such as IT and business to have become dominated by the numbers of international students”, Hewett wrote.

“While international students doing IT courses can fill a gap in some of the massive skill shortages in burgeoning areas like cybersecurity, the imbalance has led to an inferior experience for many domestic students”.

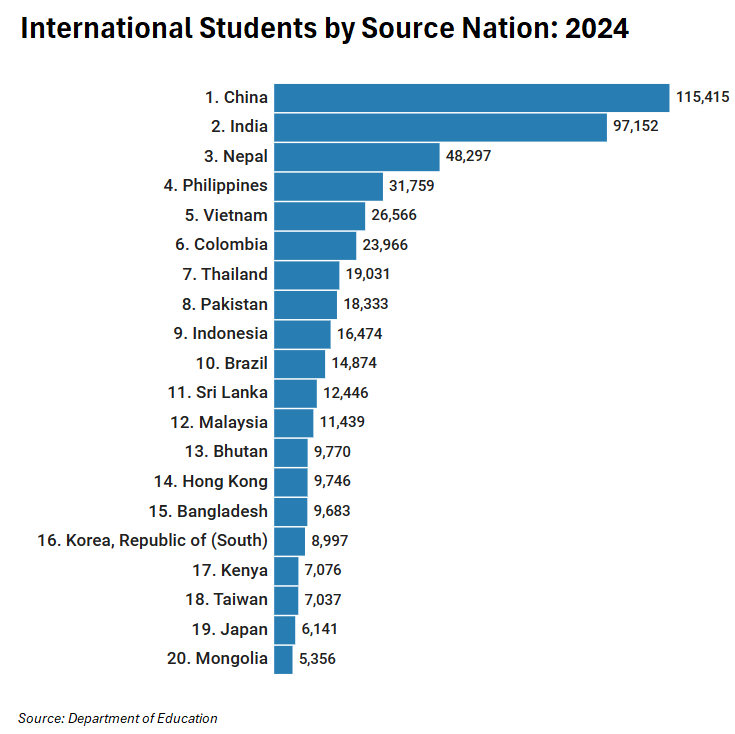

“That even includes some courses and tutorials being conducted in Mandarin, with little of the assumed benefits of supposedly a cross-cultural experience for either domestic or international students in universities that are extraordinarily large in global terms”.

“At the University of Sydney, for example, 46% of its students are now international”.

“Such universities rely on that money to fund research efforts and boost their international rankings – with the aim of attracting yet more overseas students”, Hewett wrote.

Sydney University Associate Professor Salvatore Babones made similar observations in his 2021 book, “Australia’s Universities, Can They Reform“:

“Too often, and for too long, Australian governments have enabled university behaviours that broadly disserve Australia’s students and effectively defraud Australia’s taxpayers”, Babones wrote.

“Governments headed by both major parties have allowed (and even encouraged) universities to expand international student enrolments beyond all sound pedagogical limits”…

“They have applauded the universities’ international rankings success, despite its being achieved at the cost of degraded educational experiences for domestic students”…

“Instead of enabling the self interested behaviour of Australian universities, cutting a bit here and intervening a bit there, it should insist that universities deliver—first and foremost—a quality education for Australian domestic students”…

“Over the last two decades, many of Australia’s public universities have acted irresponsibly—in their bloated international student recruitment programs, in their unbridled pursuit of international rankings, in their don’t ask, don’t tell approach to Chinese influence, and in their outright exploitation of domestic students”, Babones wrote.

Salvatore Babones elaborated on these concerns last week, noting that Australian universities’ concentrations of international students has grown to absurd levels, degrading educational quality for local students:

“Exploitation is running entire onshore courses specifically for international students, often as the price they must pay to access Australia’s low-wage labor market for convenience store clerks and Uber Eats drivers”

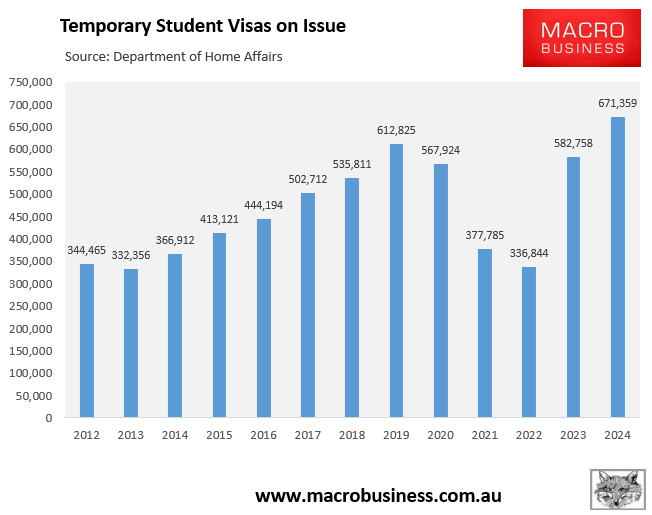

“When I arrived in 2008, Australia already had the most internationalized university system in the world. There had been a ten-year run-up in international student numbers to globally unprecedented levels. But things were only about to kick into high gear”.

“Since 2008, the number of international students at Australia’s public universities has doubled. In 2022 (the latest year for which data are available) Australian public universities were 30% international by student load. The numbers were 24% for undergraduate students and 48% for postgraduate students”.

“To put these numbers into perspective the single most internationalized public university in the entire United States (the University of Illinois) is only 23% international”.

“That’s right: the Australian system as a whole is more international than the most international public universities in America”.

Salvatore Babones, therefore, recommended in his book that caps be placed on international student numbers of 20% per course, 15% per university, and 10% from any one country:

“The Commonwealth should place pedagogically-appropriate limits on the number of international students Australian public universities are allowed to enroll”.

“The exact proportions might be determined by an expert committee, but best practice comparisons suggest something along the lines of a maximum 20% international students in any particular degree course, 15% for each university overall, and 10% from any one country”.

“Private universities might be allowed to offer courses primarily for the purpose of serving international students, but universities that receive public funds should not be competing in this space”.

“To the extent that international students enrich the educational environment for domestic students, they should be welcomed. But it should be a condition of Commonwealth funding that publicly-supported universities operate primarily in the public interest”.

In the end, Australia’s public educational institutions should exist primarily to serve the needs of Australian students, not international students. The learning experience of local students should be prioritised.

Otherwise, what’s the point of being an Australian?