Tuesday’s federal budget contained an entire section on Australia’s housing crisis.

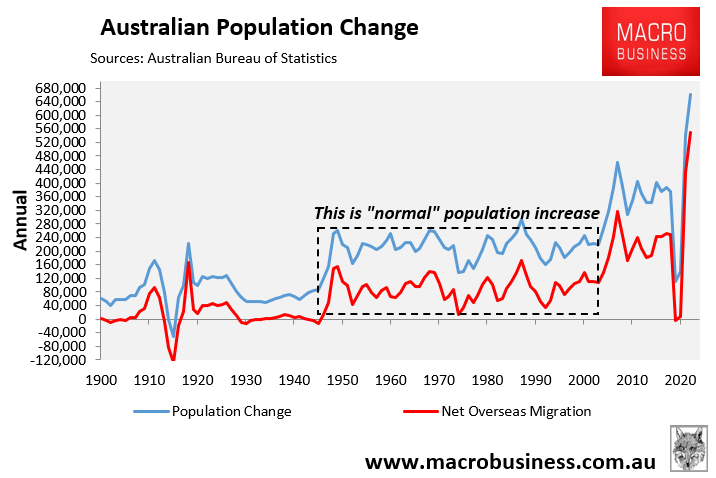

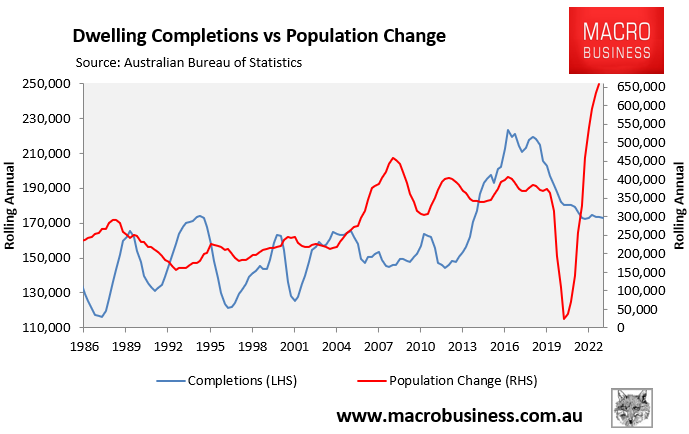

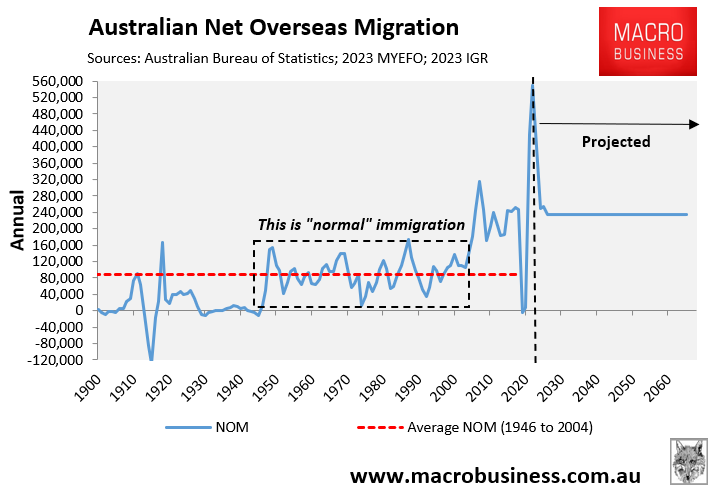

The budget admitted that Australia’s housing supply has not kept pace with turbo-charged growth in the population, which has been brought about by decades of historically high net overseas migration.

“Australia’s housing system has been unable to build enough new housing stock to keep up with the needs of our population”, the Budget states.

“This has caused a growing supply deficit, resulting in worsening affordability for both renters and first-home buyers”.

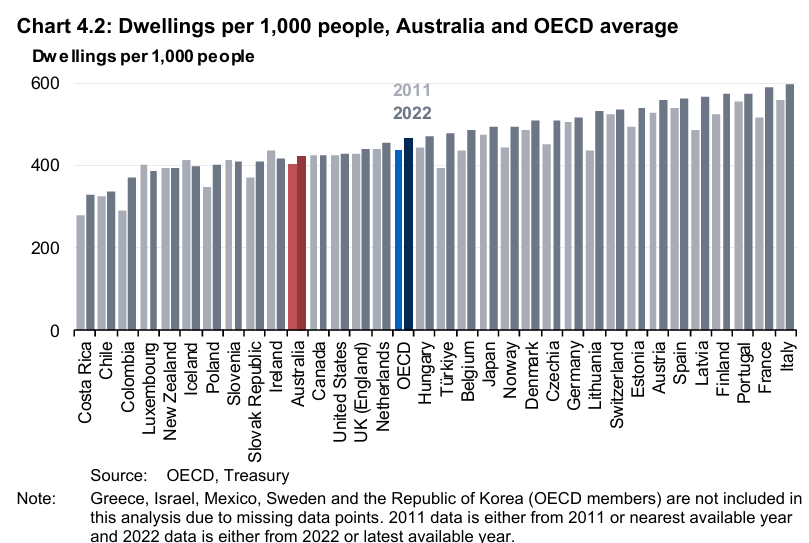

“Australia’s housing supply is low by international standards. Australia has among the lowest number of homes as a proportion of the population in the OECD”:

“Undersupply is a key factor that has driven increases in rents, mortgage repayments and house prices”, the Budget says.

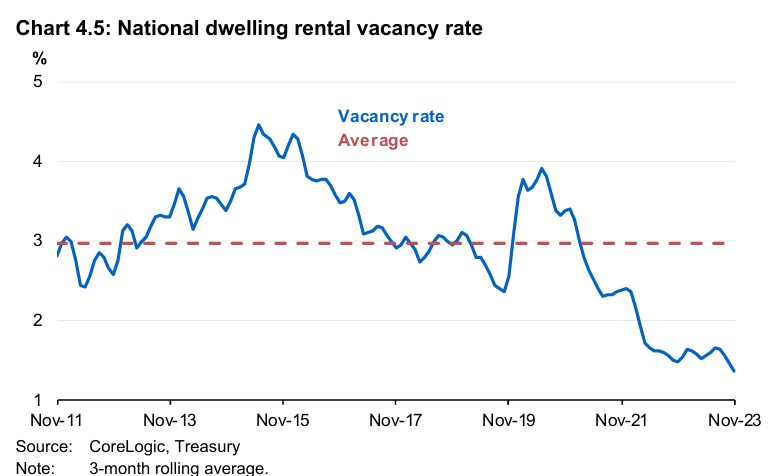

“The rental vacancy rate is well below the rate considered to reflect a balanced rental market of around 3 per cent (Chart 4.5). In some parts of the country, including some capital cities, it is as low as 0.5 per cent”:

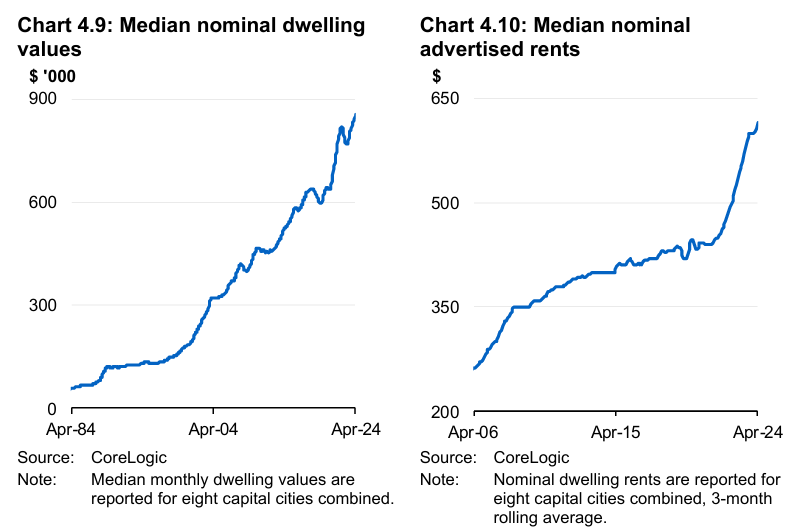

“The lag in housing supply responding to changes in population has contributed to rising house prices and worsening affordability. Charts 4.9 and 4.10 show that nominal dwelling prices and advertised rents have more than doubled since the mid-2000s”, the Budget says.

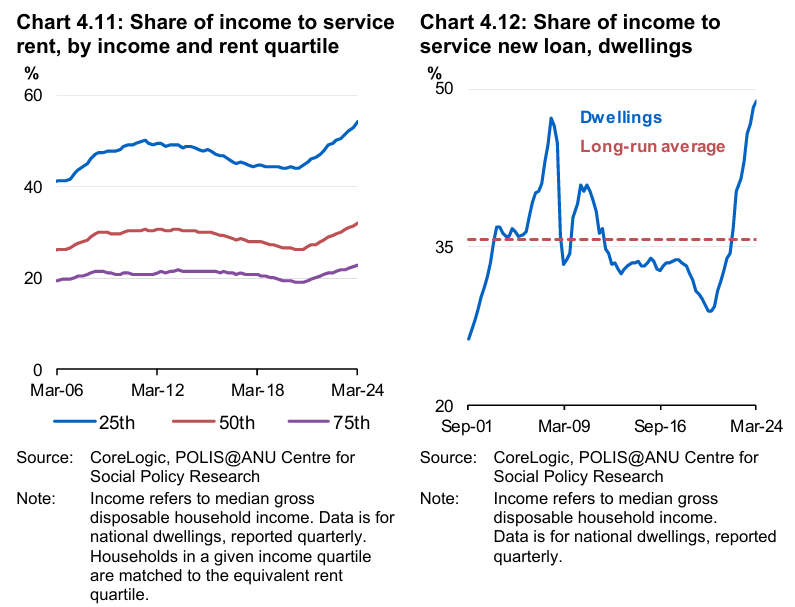

“As a result of price pressures, an increasing share of household incomes is going towards housing and housing services, particularly for lower-income rental households, with marked growth since 2020 (Chart 4.11)”.

“For prospective homebuyers, the portion of income needed to service a new loan has risen from an average of 29 per cent in 2020 to 46 per cent in 2023. This is above the long-run average of 35.7 per cent and above the 30 per cent threshold for mortgage stress (Chart 4.12)”, the Budget says.

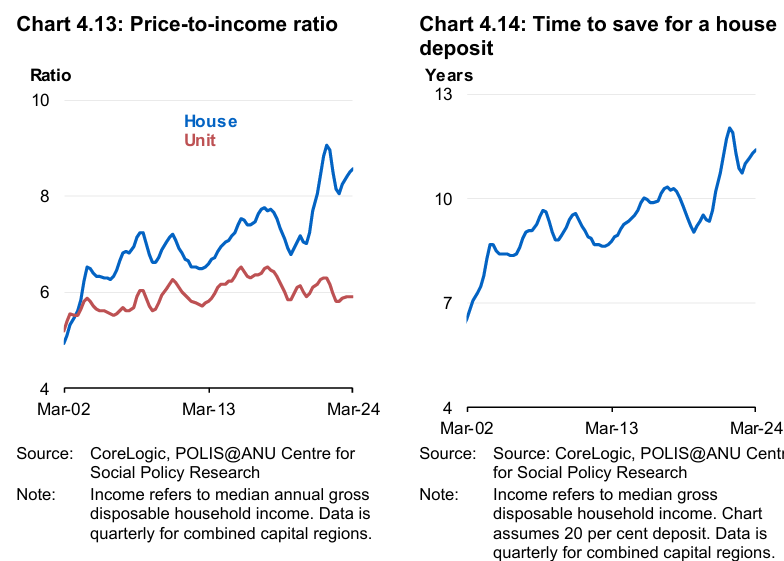

“In the March quarter of 2002, the median house price was 4.9 times the median gross disposal household income. By the March quarter of 2024, this had increased to 8.6 times median gross annual income (Chart 4.13)”.

“Australians are also taking longer to save for a deposit, with the time taken to save a 20 per cent house deposit reaching almost 11.4 years in the March quarter 2024, down from a historic peak of 12.1 years in the March quarter 2022 (Chart 4.14)”.

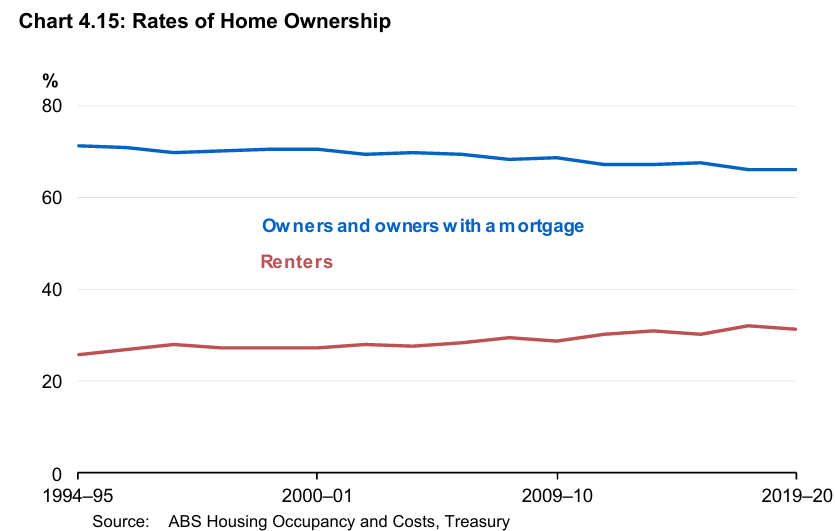

“These factors have contributed to declining rates of home ownership over time, and more people are now renting (Chart 4.15)”, the Budget says.

As usual, the budget paints the problem as a supply issue:

“Australia’s housing system has been too slow to respond to demand. The causes of this are multifaceted, complex and affect all stages of the housing construction process, including all levels of government and industry”.

“Planning and zoning and land release practices are often slow and are not effectively factoring in urgent need for housing in suburban areas”.

“Industry’s capacity to add new supply has been hampered by a lack of essential infrastructure in greenfield developments, a critical shortage of skilled labour and falling productivity in the sector”.

“At the same time, there has been a long-term, chronic under-investment in social housing”.

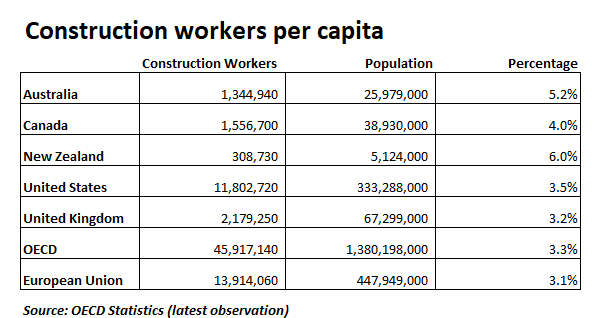

The budget conveniently neglects to mention that Australia already has one of the highest shares of construction workers in the OECD:

It also fails to mention the fastest, least expensive, and optimal solution of cutting net overseas migration to a level that is well below the nation’s capacity to build homes and infrastructure.

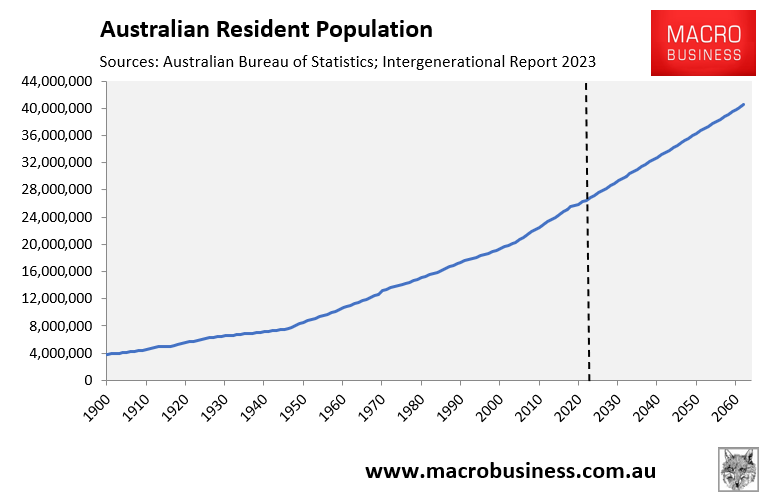

Because, under the Treasury Intergenerational Report’s migration projections, which are plotted below:

Australia’s population will swell to 40.5 million people by 2062-63, which is a 13.5 million population increase on the current level:

That 13.5 million population increase is the equivalent of adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane in only 39 years.

Australia will never build enough housing for that level of population increase.

Cut immigration instead.