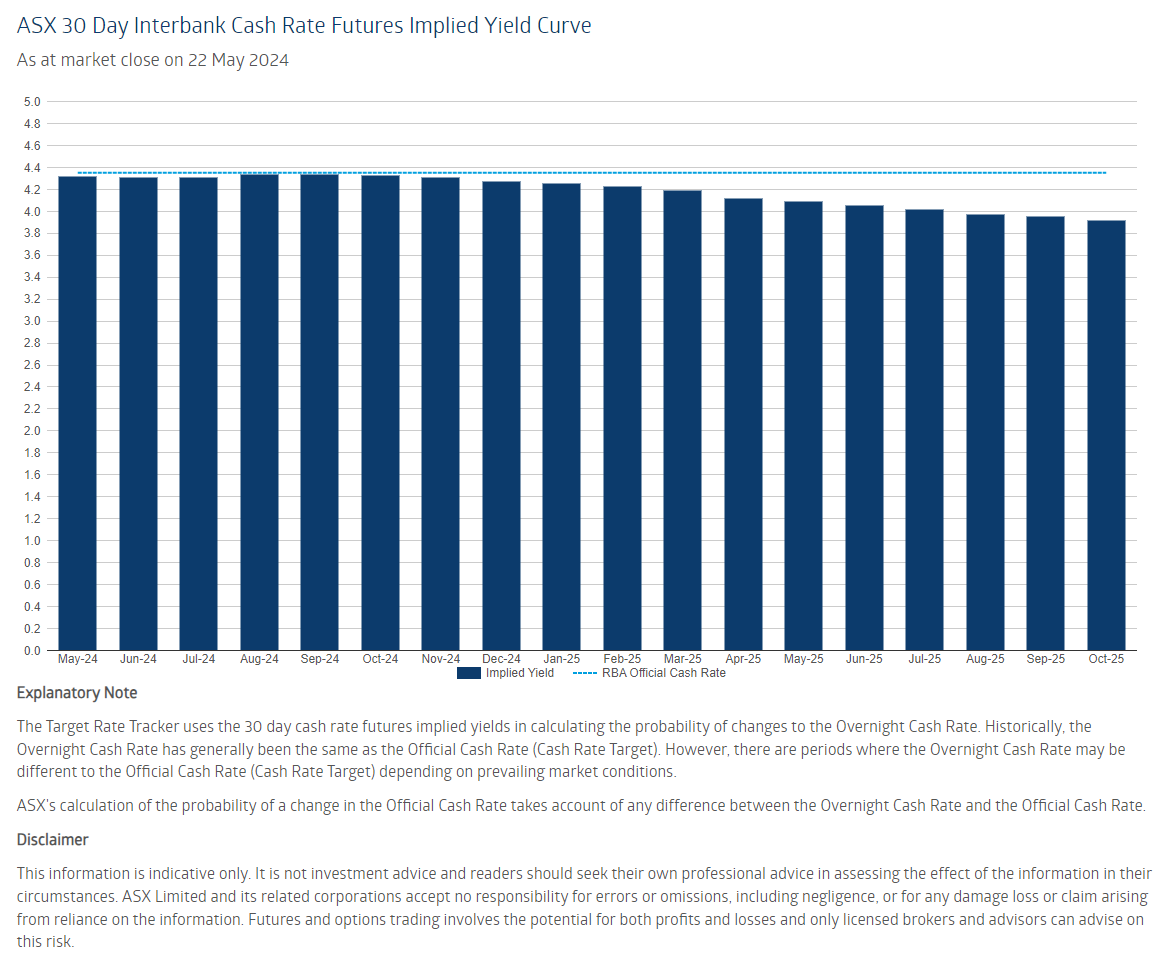

According to RBA futures, the next easing cycle will be shallow and slow over the next eighteen months:

I remain more dovish, but either way, it raises the question of how deep the next easing cycle will be.

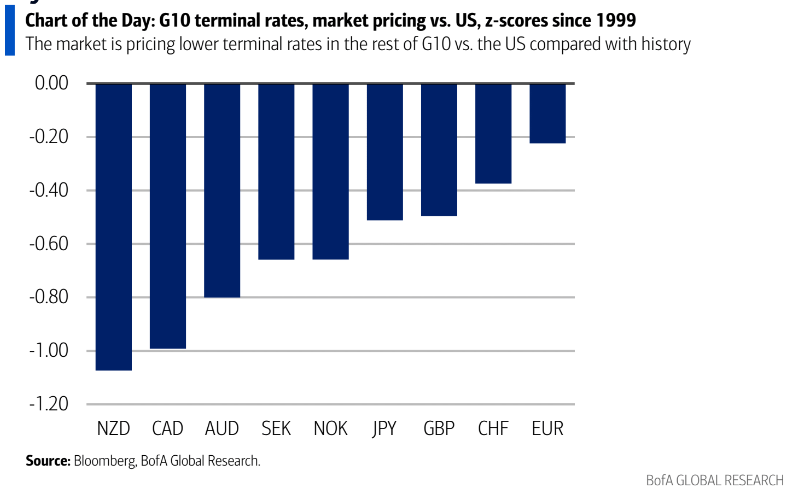

BofA has a look at that question:

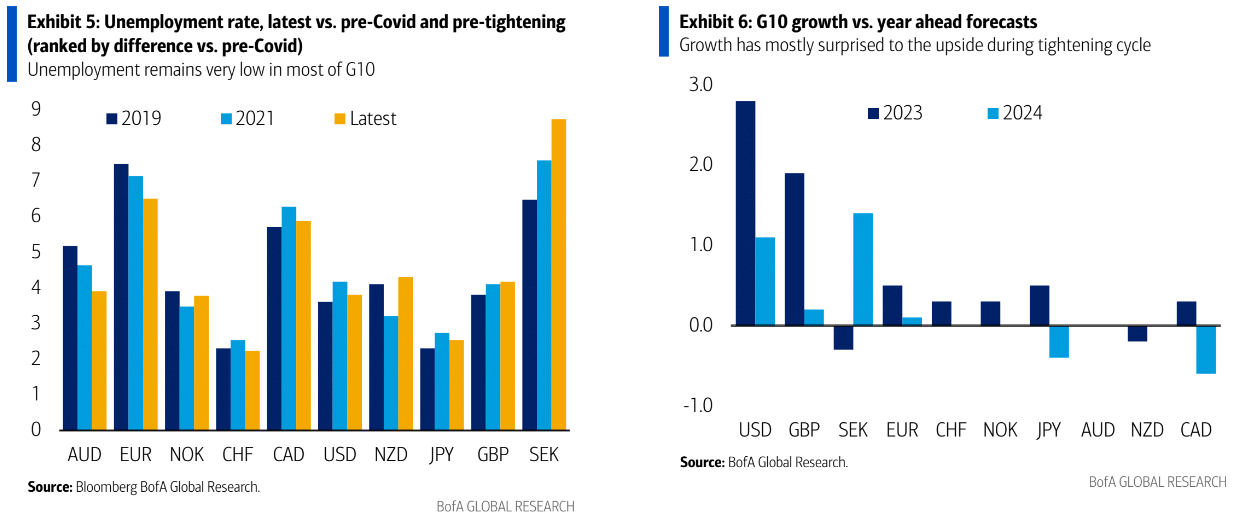

Bottom line, central banks are preparing to cut, while financial conditions are extremely loose, inflation and inflation expectations remain above their target, labor markets are tight and the economy has been performing better than expected, in most cases.

Therefore, we consider imminent rate cuts as mostly preemptive.

Despite inflation being sticky, it is moving in the right direction.

Just because the economy has avoided a landing so far, central banks should not risk a hard landing by keeping rates high for too long.

Fair enough.

However, preemptive cuts are unlikely to be aggressive.

If by cutting too early to avoid a hard landing, central banks indeed avoid a hard landing, they are not likely to go far.

The Fed still sees US-neutral rates somewhere around 2.5%. According to BofA, that would put Australia somewhere around 1.7%.

Given US private deleveraging and public spending have enabled its economy to grow at a rate of interest double this level, some may ask if the neutral rate does not require a serious update.

However, it is all about assumptions, and there are very good ones for why the long-run neutral rate is still lower than it first appears.

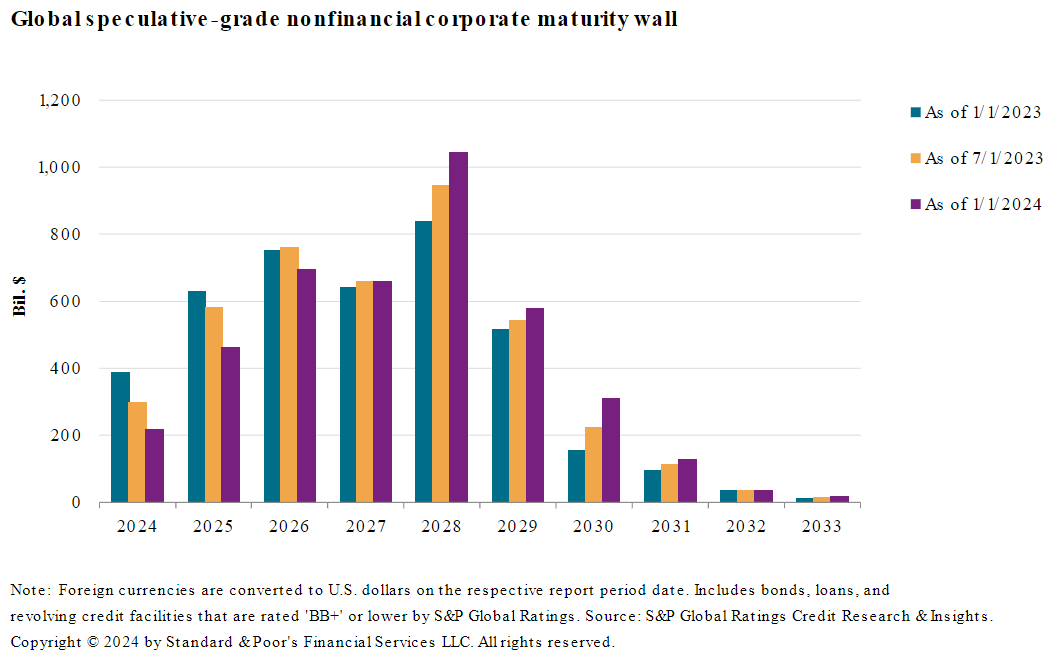

The two most prominent are the sustainability of corporate and public debt.

US corporations termed their debt during COVID, but it will still come due and represents a sudden doubling of rates when it does:

This is part of the long and lagging effects of monetary cycles. It is not large enough to derail a US cycle but enough to keep slowing it.

Nobody in Washington seems concerned about public debt other than using it as a political football, so deficits will probably continue but come down from today’s breakneck pace at rates that pressure it at the margin.

Developing AI and automation booms in the US will lift productivity and growth potential, pressuring the neutral rate.

Therefore, for the forthcoming decade, the neutral rate in the US is probably around 3%, which would put Australia at 2.2%.

These are rough estimates, to be sure, but they seem intuitively right to me.

So long as Australia follows the low-wage, mass immigration-led, labour market expansion growth model, its neutral rate will be lower than that of the US, where labour is in short supply.

Given that nobody in Canberra is structurally challenging the model and the same AI and automation forces are coming to challenge it in Australia, the gap between the US and Australia is more likely to widen through the next cycle.