The AFR’s education editor, Julie Hare, was busy once again spreading the myth that Australia’s international education sector is one of the nation’s largest exports, worth $48 billion in export dollars.

She also questioned moves to cap student numbers, noting that it places at risk “the future of this powerhouse export sector”.

“International education is something Australia excels at. The sector brought in $48 billion in export dollars in 2022-23 and employed around 200,000 people, and many more at the margins”, Hare wrote on Friday.

“As for the future of this powerhouse export sector, the feeling is one of doom and gloom. Some say the brouhaha over international students is politics over policy, sensationalism over sense”.

I have repeatedly noted that the $48 billion export figure is wildly overstated because the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) wrongly counts all expenditures by foreign students in Australia as export revenue, even if the income used to pay for such expenditures is earned working in Australia.

Associate Professor Salvatore Babones noted last week that the ABS’ rubbery export figure is arrived at by combining “an average spend estimate from Tourism Research Australia … supplemented by the addition of the total expenditure on course fees”.

“That is to say: it is based on the fantastical model that a typical international student saves up the full cost of tuition, housing, meals, and incidentals, transfers it to an Australian bank, and then lives on that money for the duration of stay in Australia”…

“The idea that all (or even a substantial portion) of the money spent by these students is transferred from abroad, rather than earned in Australia, is flatly ridiculous”, Babones wrote.

The falsity of international education imports has worsened as Australia’s international student base has pivoted away from China toward poorer South Asian nations.

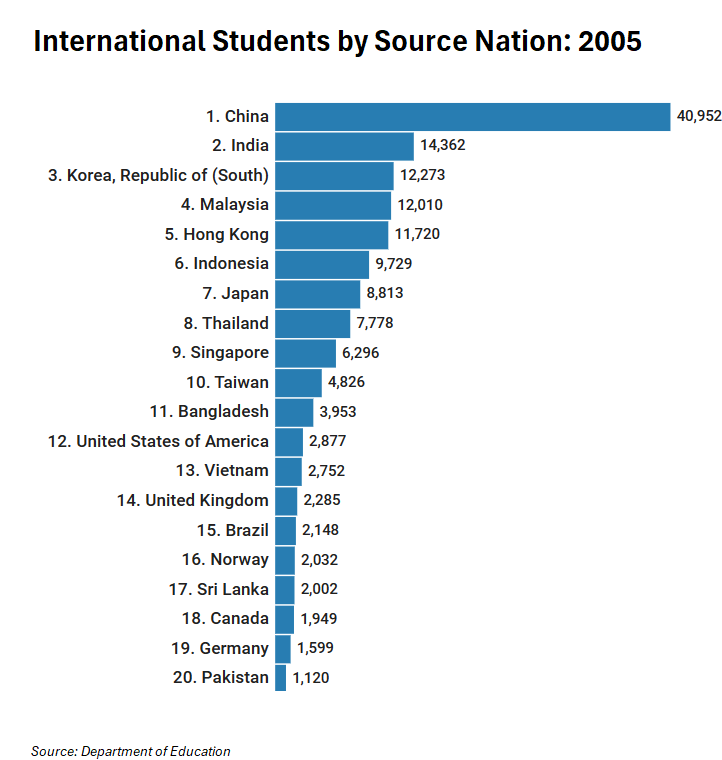

In 2005, there were 173,787 international students studying in Australia.

Chinese students (40,952) dominated enrolments, with Indian students (14,362) in a distant second place:

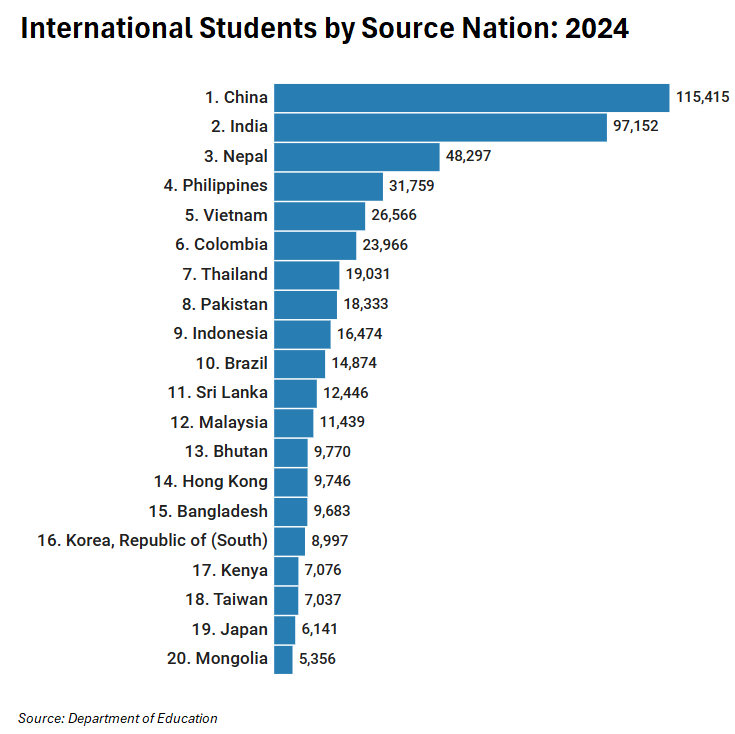

Fast forward to January 2024, there were 567,505 international students in Australia.

While Chinese students were still in first place (115,415), the number of Indian (97,152) and Nepalese (48,297) students has increased markedly:

This shift towards South Asian students raises quality concerns in Australia’s international education sector.

A recent Navitas poll of study intentions showed that students from South Asia and Africa chose a study destination based on their ability to obtain work rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency.

Only Chinese and European students care about education quality.

South Asian and African students prioritise employment and migration, and are least concerned about educational quality.

In fact, with the exception of students from China and Europe, all source countries place a high importance on the ability to work while studying and post-study job options.

As illustrated in the following chart derived from the 2016 Census, Australia has seen the greatest increase in student numbers from countries that support themselves through paid employment, whereas only a small minority of Chinese students engage in paid employment:

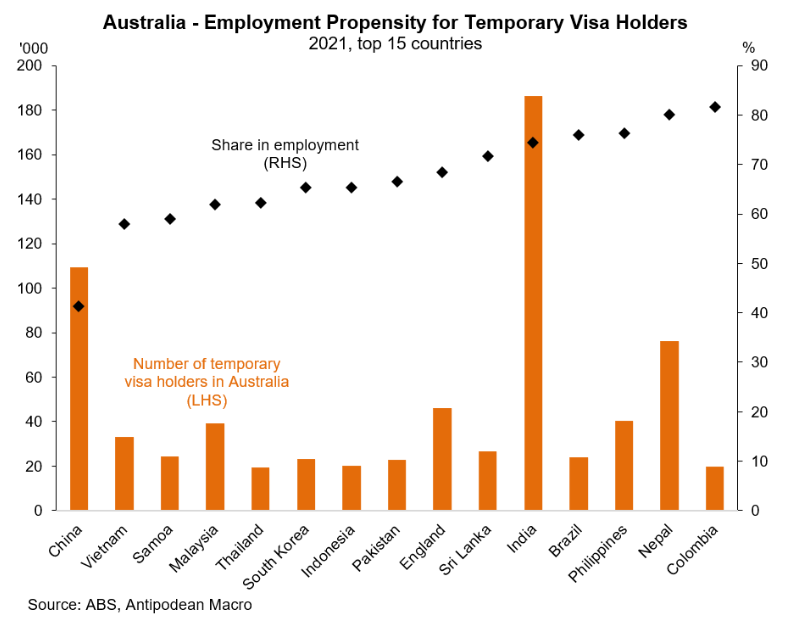

In a similar vein, the following chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro shows that Chinese temporary migrants are far less likely to be employed than temporary residents from other nations.

This disparity undoubtedly reflects the small share of Chinese students engaged in paid work.

As a result, the concept of international education ‘exports’ is only fully applicable to Chinese students, who generally pay their tuition and living expenses in Chinese yuan rather than Australian dollars.

According to Associate Professor Salvatore Babones’ latest book “Australia’s Universities, Can They Reform”:

“In reality, everyone (except perhaps the government and the universities) knew that many international students pay for their courses out of the proceeds of their work in-country, often working excessive hours under exploitative conditions, in violation of their visa terms”.

“This situation is especially common among South Asian students, and is reflected in the steep fall-off in South Asian student numbers when teaching moved online”.

“These countries are simply too poor to send large cohorts of international students to Australian universities based on family resources alone” …

“For many South Asian students, a student visa is a very expensive but thinly disguised work visa”.

The preceding analysis demonstrates why international education is primarily a people-importing immigration enterprise, rather than a legitimate education export sector.

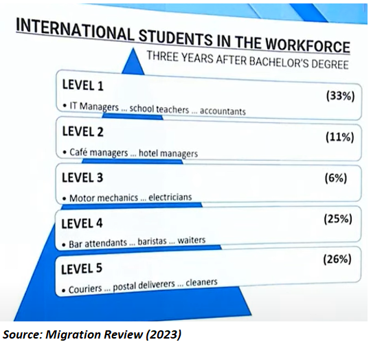

Student visas are often low-skilled work visas in disguise.

The same holds true for international graduates who have completed their studies. According to the Migration Review, 51% of international graduates with bachelor’s degrees who had been in Australia for three years worked in low-skilled jobs.

One of the benefits of the government’s crackdown on dodgy colleges is that it should see more genuine students come to Australia to study, rather than to work.

Already we have seen visa approvals for student visa applications from Pakistan, Nepal, and India plunge, with Pakistan at 46.6%, Nepal at 60%, and India at 68.6%.

By contrast, Chinese university students have been able to secure 97.2% of visa approvals.

Chinese university students, who primarily attend Group of Eight universities and depart Australia at the end of their studies, are considered low risk of misusing the visa system.

The reality is that if work rights and permanent residency were scaled back significantly, the volume of students arriving from non-Chinese source nations would plummet.