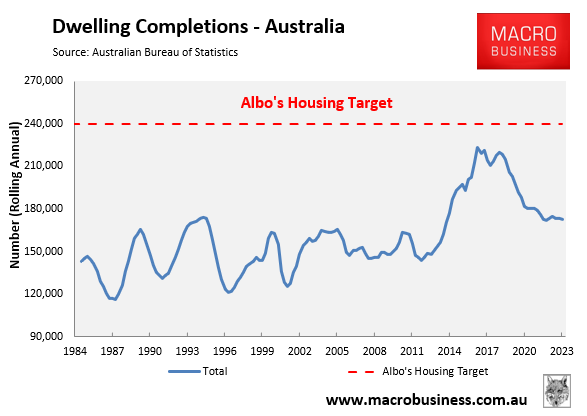

Everybody knows that the Albanese government’s target of building 1.2 million homes over five years, or 240,000 homes per year, has zero chance of being achieved.

To achieve this target, Australia would need to build 20,000 more homes than the record 220,000 average number built in 2017 and maintain this pace for five consecutive years.

Moreover, this unprecedented level of construction would need to contend with structurally higher interest rates, material costs, and labour shortages than existed in 2017.

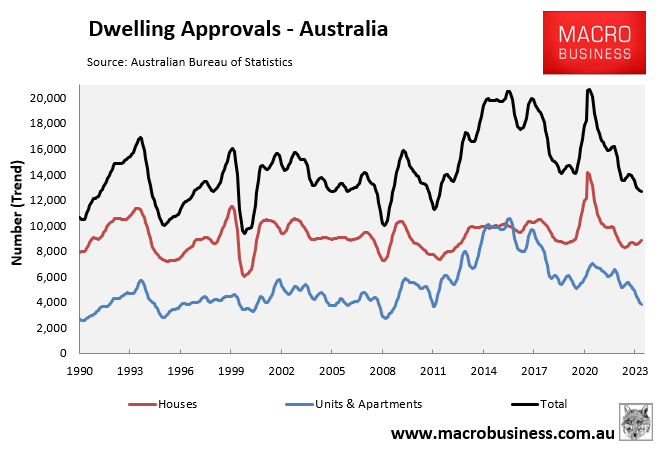

The latest dwelling approvals data has already sounded the death knell for Albo’s target, with trend approvals running at an annualised pace of only around 150,000, some 90,000 below the 240,000 required:

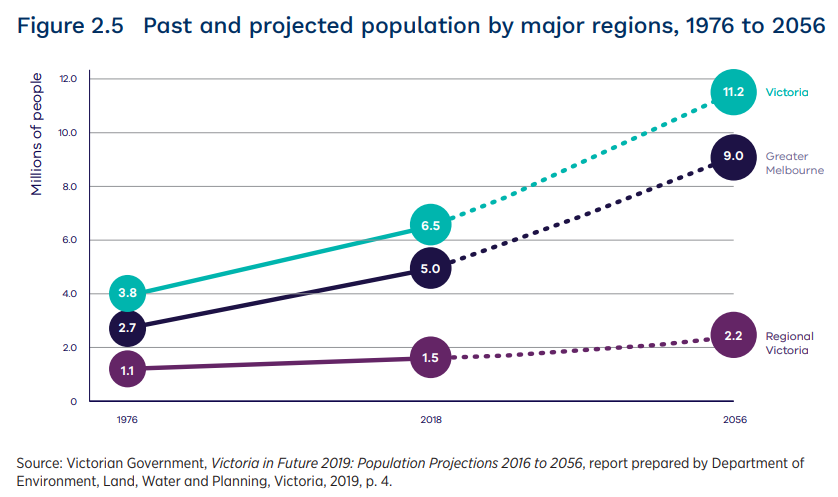

Not to be outdone, the Victorian government has announced an even loftier housing target, planning to build 2 million new homes by 2051 to keep up with the state’s rapid population growth, which is predicted to hit 11.2 million people by 2056:

To meet the target, Victoria would need to build 71,400 homes a year for 28 consecutive years – a level of construction that it has never achieved before:

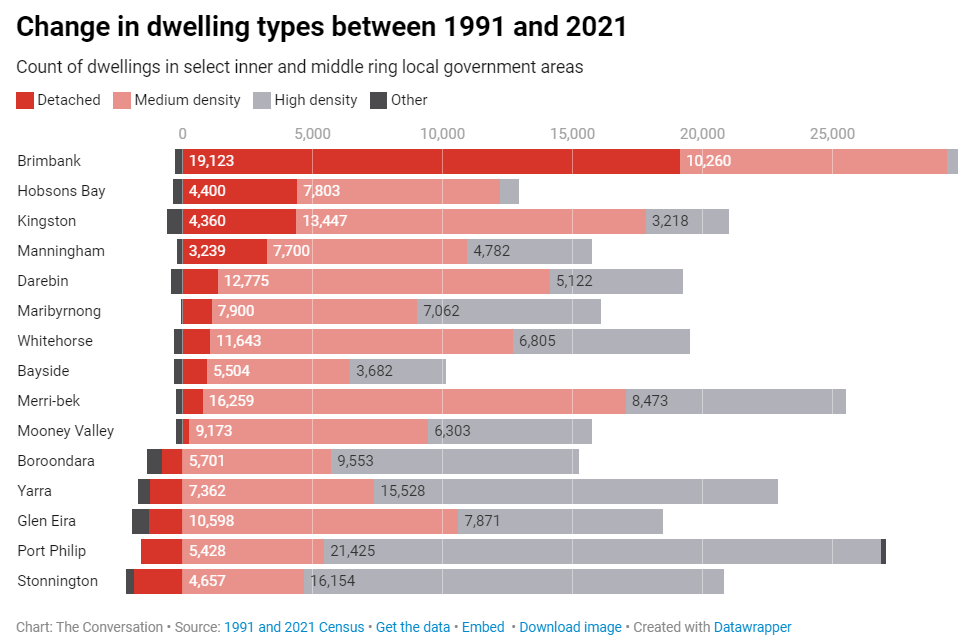

Such a level of construction would completely change Melbourne into a high-rise city.

Melbourne only had 2,057,482 at the 2021 Census, with Victoria having 2,805,661 dwellings.

Therefore, an increase of 2 million dwellings represents a 71% increase in the number of dwellings in only 30 years – an extraordinary increase in a relatively short period of time.

As David Hayward from RMIT noted, this level of construction would completely transform Melbourne’s dwelling composition into high density:

“Over the 30 years to 2021, Melbourne’s 15 main inner and middle-ring municipalities increased housing by 55%, or 318,000 dwellings. Of these, 90% were of medium and higher densities, according to my analysis of census data”.

“Detached housing in these areas has fallen from 66% to barely 50% over that period. If the government’s targets were met, detached houses would be under 33%”.

Hayward also warned that the Victorian government’s housing targets would likely cause a sharp decline in dwelling quality:

“If councils are forced to approve more and more developments with no guarantee they will even be started, it is likely planning standards will drop”.

In other words, we would repeat the what happened last decade when Melbourne was inundated with defective high-rise apartments, only on steroids.

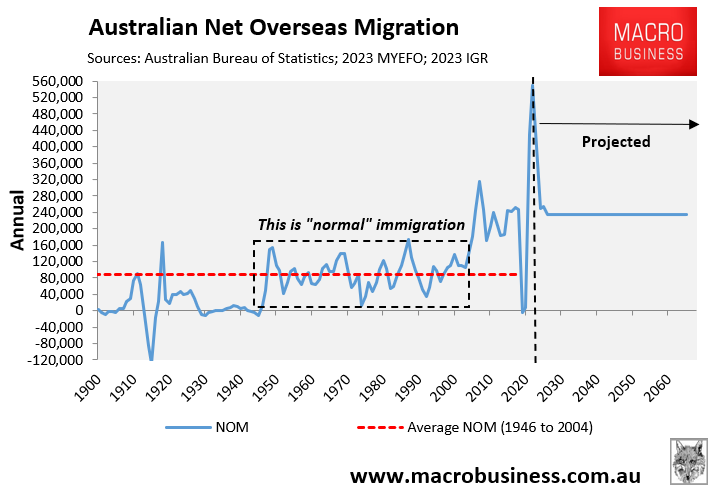

Instead of continually chasing our tail to keep pace with the federal government’s extreme immigration policy, the Victorian government should demand that the federal government reduce net overseas migration to sensible and sustainable levels of less than 120,000 a year:

Few people in Melbourne want the city’s population to surge to 9.0 million by 2056 and for the city to transform into Asian-style high-rise.

Residents are already struggling under the weight of 20 years of rapid population growth, which has seen Melbourne’s population balloon by 1.6 million people since 2005.