The Grattan Institute has published a report arguing that Australia should reform the points-tested skilled permanent visa system.

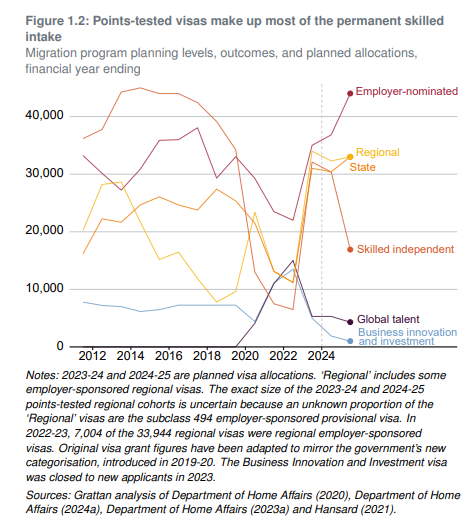

Points-tested visas, which assign points to potential migrants based on their age, English language ability, education, and work experience, have accounted for about two-thirds of all permanent skilled visas issued in the last decade.

Based on present patterns, Grattan predicts that Australia will issue approximately 800,000 points-tested visas over the next decade.

Separate state and regional points-tested visas account for approximately two-thirds of all points-tested visas (see below chart).

However, migrants chosen for these visas tend to gain fewer points, work in lower-skilled occupations, and earn less during their career than other skilled migrants.

Accordingly, Grattan recommends that state and regional points-tested visa programs be abolished in favour of more skilled independent visas offered.

Grattan also wants the points test changed to better reward the most highly-educated applicants and those with strong English language skills.

While I agree with the thrust of Grattan’s proposed reforms, I believe that points tested permanent visas should be abolished altogether in favour of employer-sponsored visas.

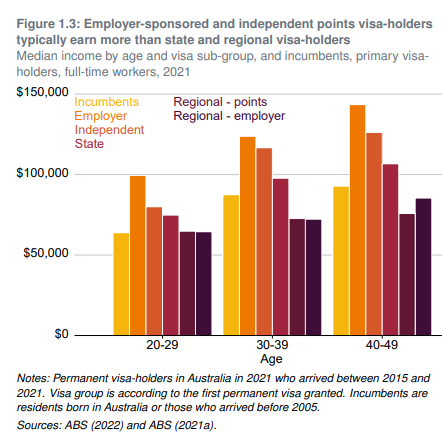

Employer-sponsored visas have by far the best labour market outcomes in terms of employment rates, participation, and earnings.

Employers who are willing to sponsor and hire a skilled migrant can nominate them for a permanent visa, making them ‘demand-driven’.

Skilled migrants nominated through employer-sponsored visas already have jobs lined up or are already temporary migrants working in jobs in Australia. Therefore, they have good labour market outcomes and have generally already proven themselves.

The pay floor for these employer-sponsored migrants should then be set at a rate higher than the median full-time salary (~$90,000 currently).

As an aside, the above chart is misleading and makes skilled migrants out to earn more than they actually do, while understating the pay of incumbent residents.

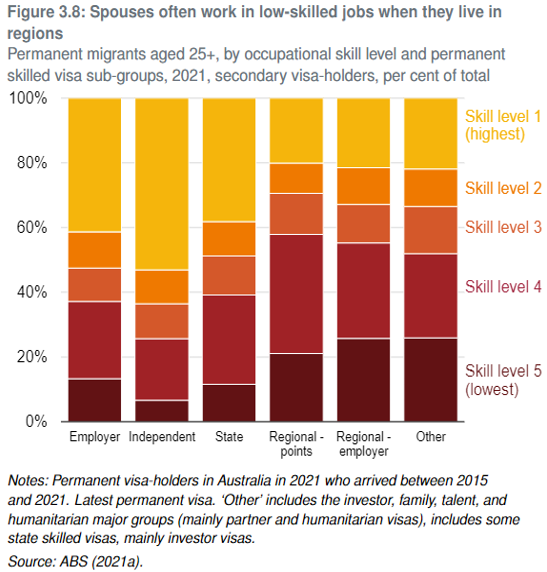

First, the chart only plots primary skilled migrants and not their spouses, who lend to work in lower skilled jobs and get paid far less.

Second, Grattan has chosen to compare the median full-time earnings of primary permanent skilled migrants against the median earnings of incumbent Australians, which includes unskilled workers.

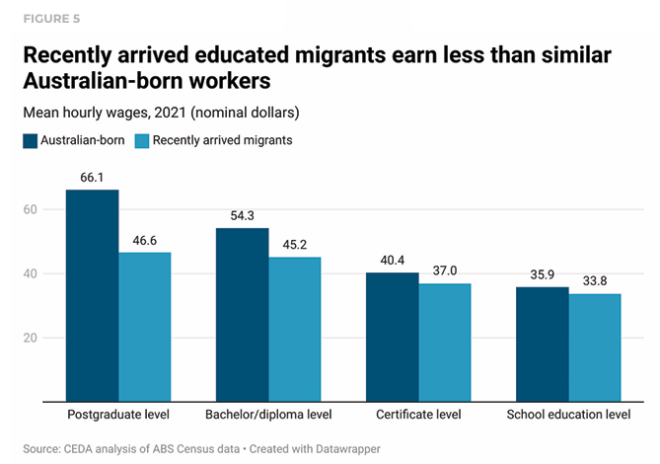

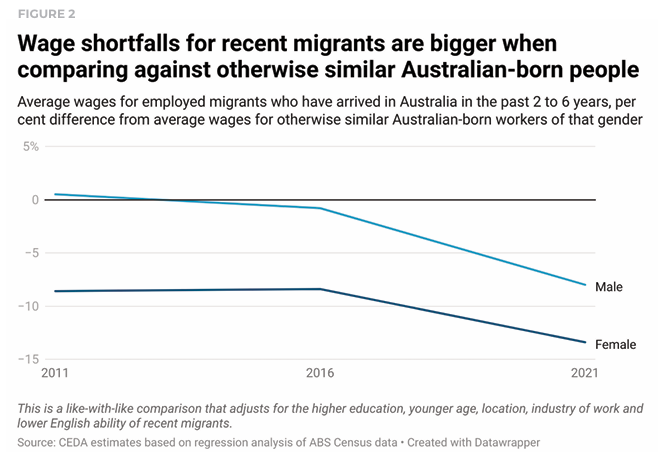

If Grattan had bothered to compare skilled permanent migrants against skilled incumbent Australians, it would have shown that skilled permanent migrants actually get paid more than 10% less than incumbent skilled Australian workers, according to research from the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA).

As you can see, higher-educated migrants have the largest shortfall in earnings compared with skilled Australian workers:

CEDA also found that “migrants have become increasingly likely to work in lower productivity firms”:

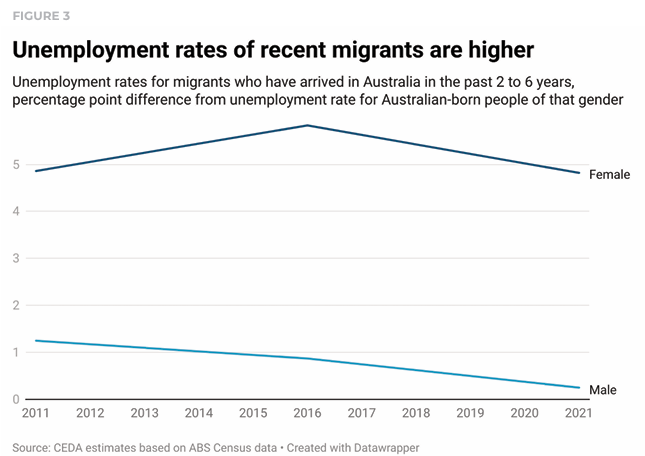

Unemployment rates for recent skilled migrants are also higher than for Australian-born workers:

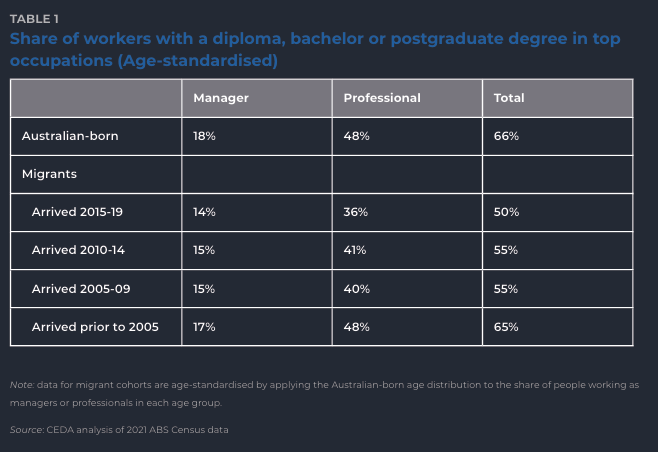

Migrants are also far less likely to work in professional or managerial jobs:

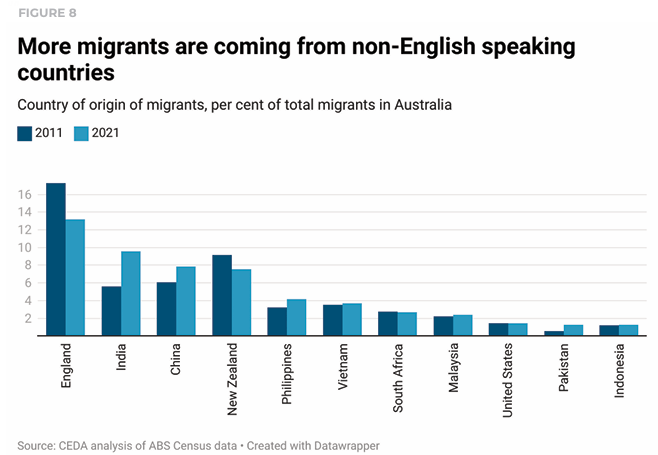

Part of this poor labour market performance of skilled migrants relates to the fact that Australia’s migration system has shifted to non-English-speaking nations:

The above data from CEDA highlights why Australia’s permanent skilled visa system should move to a high wage employer-sponsored system only.

Economic benefits would be maximised through Australia having a smaller volume of highly skilled migrants, not large numbers of moderately skilled migrants.