On Thursday, Statistics New Zealand released national accounts data for the March quarter, which showed that the economy emerged from a technical recession, growing by 0.2%.

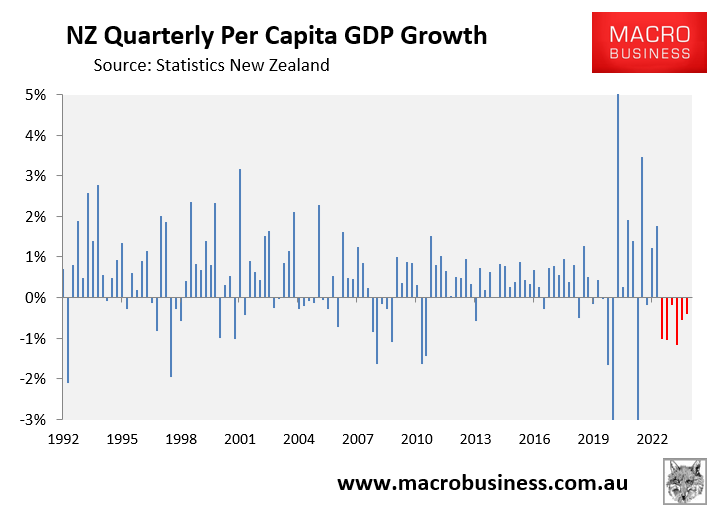

However, owing to New Zealand’s historically high population growth (immigration), GDP in per capita terms fell by 0.3%—the sixth consecutive quarterly decline.

This meant that New Zealand’s per capita GDP fell a hefty 2.4% in the year to March 2024.

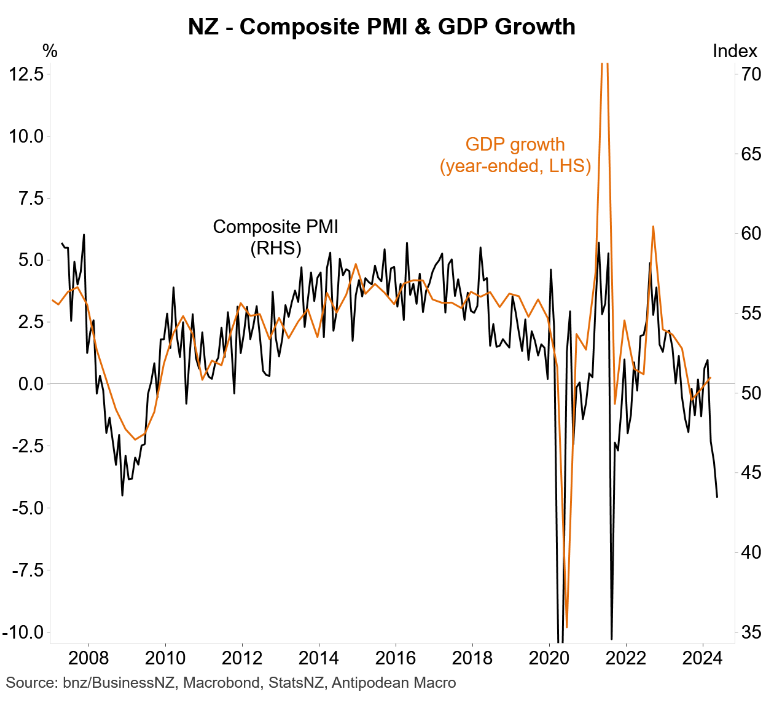

To add further insult to injury, the composite PMI is pointing to weaker growth in the June quarter, which should extend New Zealand’s run of per capita GDP declines to a record equalling seven consecutive quarters.

With this background in mind, independent economist Tony Alexander has penned an interesting note explaining why this is a recession that New Zealand had to have.

When the tide goes out

Most people, when considering the currently weak and depressed state of the New Zealand economy, will blame the Reserve Bank…

They kept pumping money into the economy and held interest rates too low for too long despite having the largest group of economists in the country who should have seen the economy did not need that sugar any longer.

If you are losing your business this year, then you can rightly blame the Reserve Bank’s 2021 incompetence to a great degree.

But there is more in play than just their change in role from a stabilising to a destabilising force in the economy.

There has been a lot of special assistance provided to our economy over the past quarter of a century and we have had our own version of what the Americans used to call the “Greenspan put”.

This was a reference to the way that the Federal Reserve would quickly step in to cut interest rates and boost growth if the US economy started to look unusually weak. It was notably associated with the cutting of their overnight funds rate to 1% in 2002.

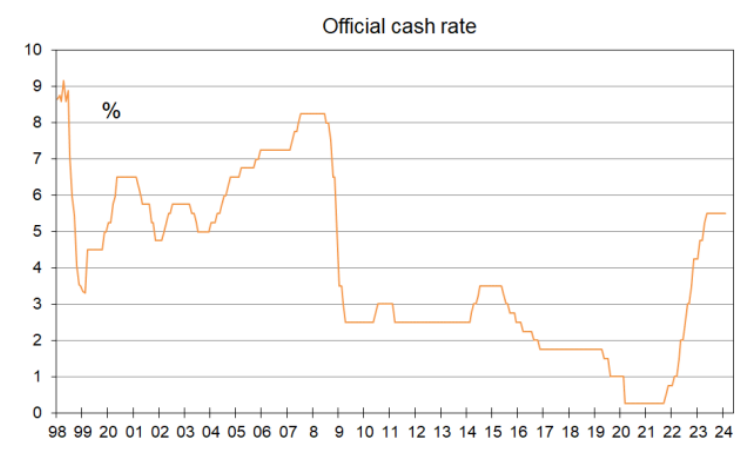

When the Asian Financial Crisis struck New Zealand over 1997/98 at the same time as there was an extended drought, we saw a quick easing of monetary policy.

The yield on 90-day bank bills (the current cash rate was not introduced until March 1999) fell from over 9% early in 1998 to 4.5% by the end of the year. Note that. When our central bank acknowledges policy needs to be eased they act quickly and interest rates lose height at a fast pace.

When the dot-com sharemarket crash happened in 2000 the NZ economy eventually weakened and the official cash rate was quickly cut from 6.5% early in 2001 to 4.75%.

The assisting factor back then was ham-fisted policy implementation by the new Clark-Cullen Labour government and the ”winter of discontent” in the business sector.

When our economy entered recession in 2008 and shortly after the GFC happened the cash rate was slashed from 8.25% to 2.5% within ten months from mid-2008.

Then we went down the rabbit hole in the latter years of the 2010s decade. Inflation failed to spark following the GFC ending and deflation worries gripped the Western world from around 2018.

As a result, despite the unemployment rate ending 2018 at 4.3% and the economy recording 3.5% growth that year the Reserve Bank cut the cash rate to a record low of 1% through 2019.

Then when the pandemic struck and they had little ammunition left for the cash rate weapon they embarked on their huge money printing and cheap bank funding exercises.

The upshot and the point I wish to make is this. In the past, when the crap has hit the fan, the Reserve Bank have jumped in to save the day with large policy easing. That is not happening now.

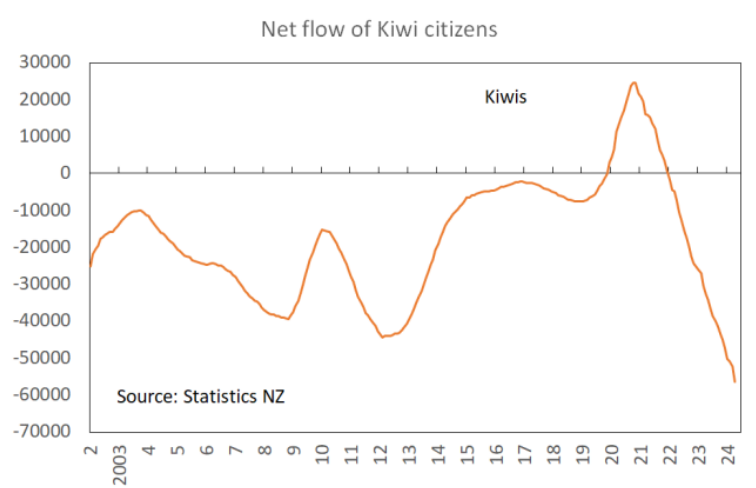

We are back deep in the excrement with the economy recording barely any growth for a year and a half. Jobs growth stopped in the middle of last year, retail spending volumes per capita are down almost 11% from two years ago, government debt levels have blown out these past six years for zero reward to our society, house construction is falling rapidly and we Kiwis are doing what we’ve always done when this dystopia comes along.

We’re leaving. The net Kiwi migration loss has hit a record 56,500 in the past year.

So now the kicker. Despite all of this woe the Reserve Bank are not riding to the rescue. We know they want to because they are cut from the same woke cloth as the previous government. But they can’t because inflation is 4% and forward measures of where inflation is going remain much too high for even us RB-bashing private sector economics to demand they cut rates now. I wouldn’t.

My view is that by the December quarter of this year the extent of weakness in the economy will be great enough that the Reserve Bank’s anticipation of extra lagged decline in inflation because of that will overwhelm potentially still worrying forward pricing measures to encourage policy easing.

But before we get there the pain is going to get a lot worse. The media will be filled with many more stories of woe across a lot of sectors and especially the three I’ve been highlighting for a long time. They are retailing, residential construction (the cream is rising to the top in that sector), and hospitality.

So, what do I mean by the title of this article – when the tide goes out?

It is a reference to the very well known comment made by Warren Buffett.

“Only when the tide goes out do you learn who has been swimming naked.” (I couldn’t find when he first said it. Maybe 1994.)

It means when the tide is rising all boats are lifting, businesses and households are doing well, mistakes get quickly covered up, risk taking does not seem risky at all, and almost any fool can do okay.

But take away the extraordinarily generous economic conditions and those with insufficient ability and capital will be left naked and exposed, their inadequacies on show for all to see.

That is what is happening now. Without the Reserve Bank’s sugar and without their quick throwing of such sugar on the economic fire when times are tough the under-capitalised, overoptimistic, least experienced operators across all sectors are being exposed.

This year is about many of them getting weeded out. That also means this year will prove to be the best for those who have ridden the tides over the years because they will pick up discounted assets.

This year, therefore, presents the best opportunity for a productivity boost that we have seen for a long time. Capitalism needs periods when low yielding assets get reallocated to better yielding activities, and ineffective managers of assets and capital get trimmed away. It is painful but it is also necessary.

The unfortunate thing is that the pain will hit many people who have no experience of fending for themselves without special central government or Reserve Bank assistance. They can’t find the “safe space”. They are the ones I feel sorry for. This is new to them, whereas older folk who have lived through the reform years have seen worse.

The weeding out can’t be stopped. But as noted here previously, it would be a good idea to keep an especially close eye on your friends and relatives who may be struggling.

They may have been raised in a schooling environment where risky play was discouraged and they haven’t built the resilience yet to handle falls and knockbacks by themselves. They won’t understand what is going on and that may be where the personal attacks against high ranking people come from.

The state of the economy, housing market, and general feelings of people will get worse before things improve through 2025.