Two of the biggest lies surrounding Australia’s “world-class” international education sector have been exposed.

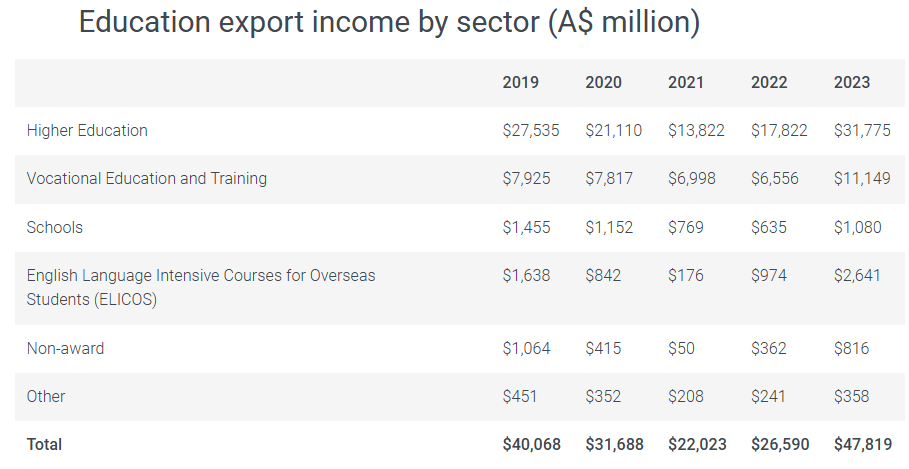

The first relates to Australia’s fantastical $48 billion education exports, which were categorically debunked on Tuesday.

Source: Department of Education based on ABS data

This mythical figure is estimated by the ABS by combining “an average spend estimate from Tourism Research Australia … supplemented by the addition of the total expenditure on course fees”.

The ABS wrongly classifies all spending by anyone on a student visa as an export, even if the expenditures are funded via money earned by working in Australia.

Hilariously, student visa holders are the only category of migrant whose expenditure is treated as an export for the duration of their visa.

Therefore, if an international student Uber driver on their fifth year of their visa fills up with petrol, it is counted as an export. Whereas if a newly arrived temporary migrant on a skilled visa fills up with petrol, it is not counted as an export.

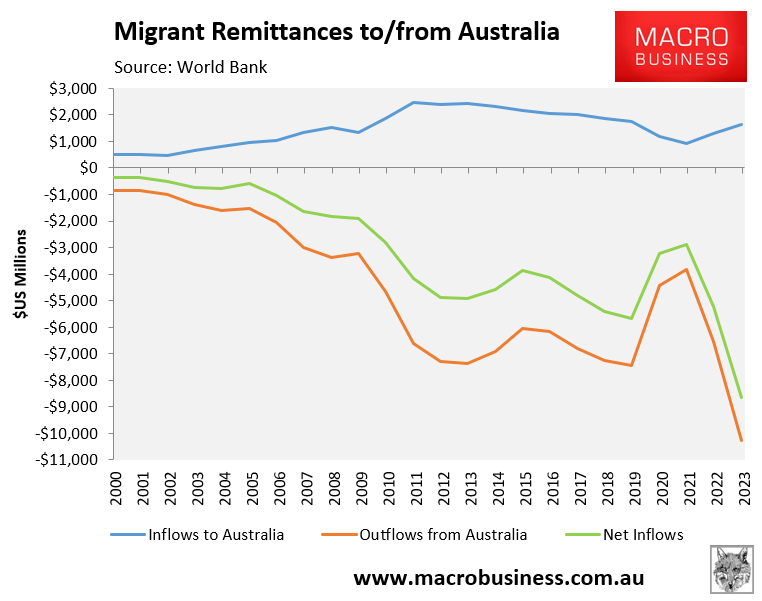

The World Bank’s migrant remittance data from Australia disproves the idea that international education is a significant export (or even an export at all).

This data shows that migrant remittance inflows into Australia were only valued at $US1.6 billion in 2023 and were tracking well below the peak of $US2.45 billion in 2011.

By contrast, migrant remittance outflows from Australia were valued at $US10.3 billion in 2023, giving a record net outflow of $US8.6 billion.

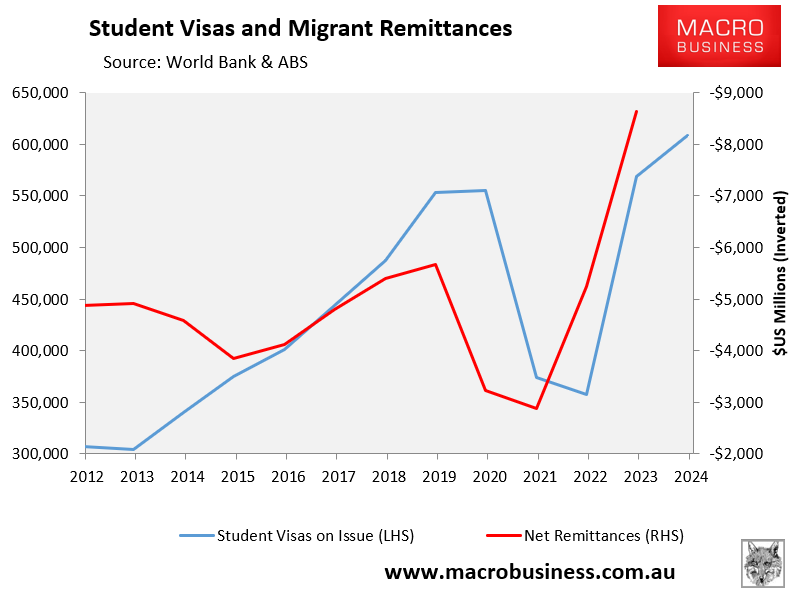

Curiously, the net outflow of remittances has more or less tracked the rise of student visa holders:

Therefore, how can international education be considered a gigantic $48 billion export industry when billions of dollars of net remittances are flowing out of Australia? Follow the money.

The second big lie is that international education improves the productivity of the Australian economy.

This lie was parroted yet again on Tuesday by the usual lobbyists.

“Imposing caps on international student enrolments will have long lasting, damaging consequences for our economy, our capacity to attract the highest-quality students, our skilled workforce and Australia’s international reputation”, GO8 chief executive Vicki Thomson said.

“Australia needs high quality, high achieving graduates who will contribute to our economic and social prosperity”.

“It (international education) is a huge export earner for Australia. It’s fundamental to our skills and training system”, Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry chief executive Andrew McKellar said.

Only for Caitlin Cassidy of The Guardian to completely expose them:

From the article:

International students who cannot speak “basic English” are walking away from Australian universities with prestigious degrees, academics say, a situation one described as “mind-blowing” .

More than a dozen academics and students who spoke to Guardian Australia, most on the condition of anonymity, said the universities’ financial reliance on foreign students over many years had hollowed out academic integrity and threatened the international credibility of the sector.

Many said the rise of artificial intelligence was accelerating the crisis to the point where the only way to fail a course would be to hand nothing in, unless universities came up with a coherent institutional response.

A tutor in an arts subject at a leading sandstone university said in recent years the number of overseas students in her classes – who may pay up to $300,000 in upfront costs – had reached as high as 80%.

“Most can’t speak, write or understand basic English,” she said. “They use translators or text capture to translate the lectures and tutorials, translation aids to read the literature and ChatGPT to generate ideas.

“It’s mind blowing that you can walk away with a master’s degree in a variety of subjects without being able to understand a sentence”…

Academics who spoke to Guardian Australia said they were continuing to teach courses where as many as half of their cohort did not appear to understand the content, yet still passed. Many blamed an institutional reliance on international student fees.

An academic who was a sessional teacher for two decades and recently retired said universities that were “once centres of excellence” had become “profit centres chasing enrolments and revenue”.

The academic, who wished to remain anonymous, said supervisors and coordinators in his faculty were “interrogated” if students were failing.

“It breaks my heart reading essay after essay with a strong suspicion students couldn’t have written it,” they said. “The writing is on par with mine but when I ask [students] what a citation and a reference is, they have no idea.

“I’ve interviewed students after grading with suspicions and they could not tell me a single thing about the entire semester, yet wrote beautiful posts online and a beautiful essay”…

Dr Andrew Paterson, a former lecturer in social work at Flinders University, cited master’s tutorials in which more than 50% of the students had language issues that were “obvious and clear”…

“It’s a shambles,” he said. “We’re pretending these students are serious, and they’re pretending they’re interested [in the content]. It doesn’t make for a creative academic environment.

These are the same arguments that MB has made for nearly a decade.

The entire international education industry is built on a foundation of lies and designed to enrich senior executives in the industry, while domestic students and the broader community bear the costs.

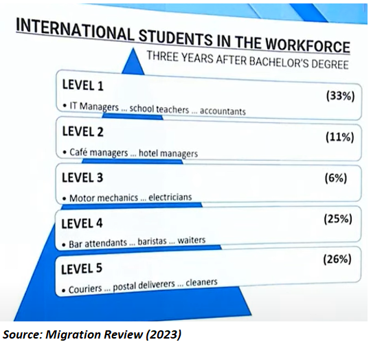

Is there any wonder that Labor’s Migration Review showed that more than half (51%) of international student graduates with bachelor’s degrees were working in low-skilled jobs three years after graduation:

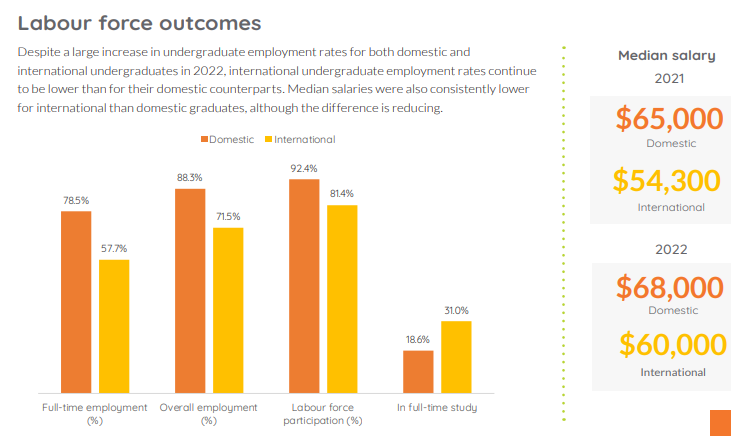

Or why the Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS) consistently shows that international graduate employment rates, participation rates and median salaries are well below those of domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

It is a sad indictment on Australia’s universities that they are producing so many international graduates that work in low-skilled and low-paid jobs. It is also one of the drivers of Australia’s low productivity.

Hilariously, the Australian Universities Accord – Final Report, released this year by the Albanese government, stated the following with regards to higher education:

Australia should aspire to be a world leader in delivering innovative, best practice learning and teaching – not only maintaining but improving higher education student experience and outcomes as the system grows.

This means pursuing excellence in learning and teaching at a system-wide level and moving beyond the current threshold standard approach to quality.

Graduate employment outcomes are substantially lower for international students than their domestic counterparts.

This poses a risk to Australia’s standing as a provider of high-quality international education.

It is vital to improve learning outcomes and student experiences for all students, encompassing international students in addition to domestic students.

Given the evidence presented above, Australia’s international education trade is clearly working against the aims of the Universities Accord.

If the federal government was serious about reforming the international education sector, it would:

- Raise financial barriers to entry (i.e., how much funds a student must have available before arriving in Australia).

- Significantly increase entrance requirements (e.g. English language proficiency and academic testing).

- Raise pedagogical standards.

- Abolish group assignments.

- Cut the clear link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

- Require universities to provide on-campus accommodation to international students in proportion to their enrolments.

Australia must aim for a smaller cohort of high quality students. The focus must be on quality over quantity.

Below is a video explaining the themes captured in this article.