AMP deputy chief economist Diana Mousina has released a report examining Australia’s housing market.

Mousina claims that “housing demand in Australia has been running above housing supply for the past two decades causing a dwelling shortage”.

Housing demand is determined mostly by “population growth (mostly driven by net overseas migration)”, whereas “housing supply is determined by completions of homes, after taking into account demolitions, conversions and vacant properties”.

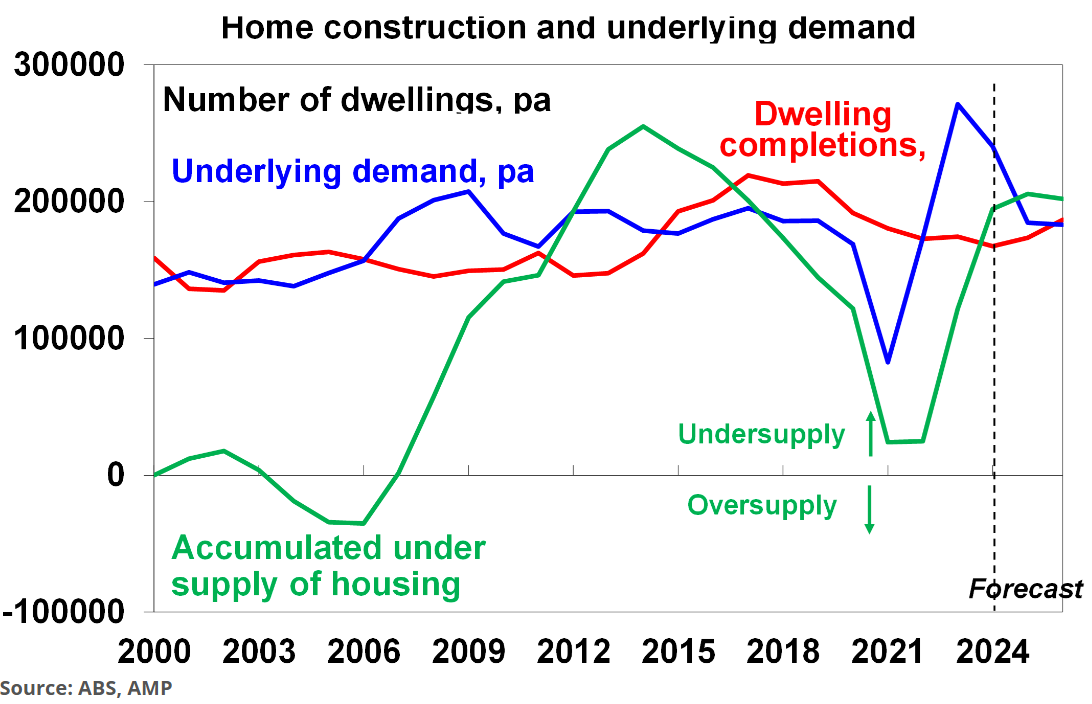

Mousina notes that “prior to 2000, housing demand and supply were fairly balanced in Australia. After this time, housing demand started running above supply, with persistent undersupply ramping up from 2005”, as illustrated in the chart above.

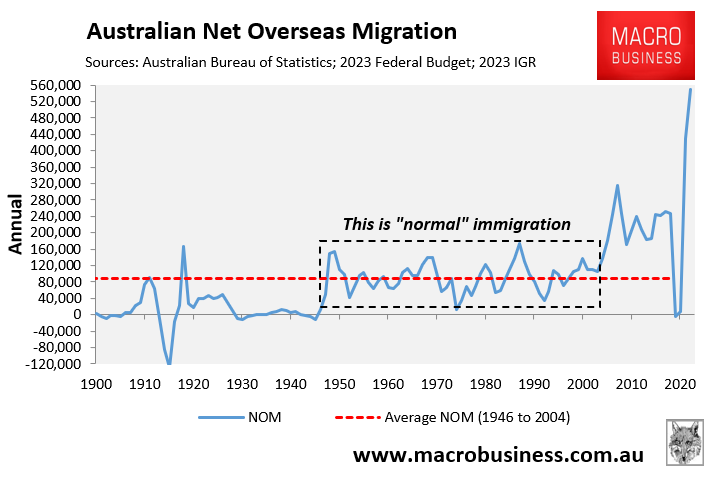

The mid-2000s was when the federal government more than doubled net overseas migration, as illustrated below:

Therefore, the ramp-up in immigration drove the nation’s chronic housing shortage.

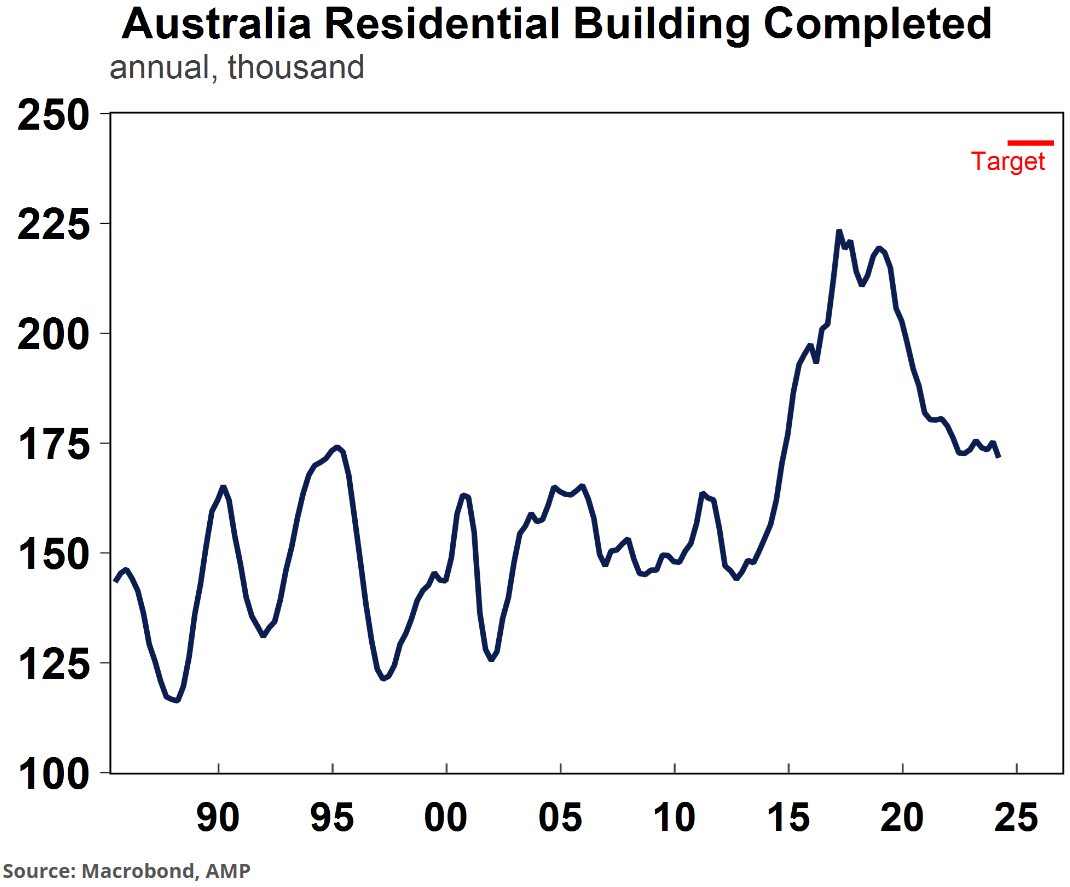

AMP estimates that “housing demand is currently running around 240K and will slow to 185K over the next few years as population growth subsides. Housing supply is expected to be ~167K in 2024 and average around 180K in the out-years which means that the housing supply shortage will continue”.

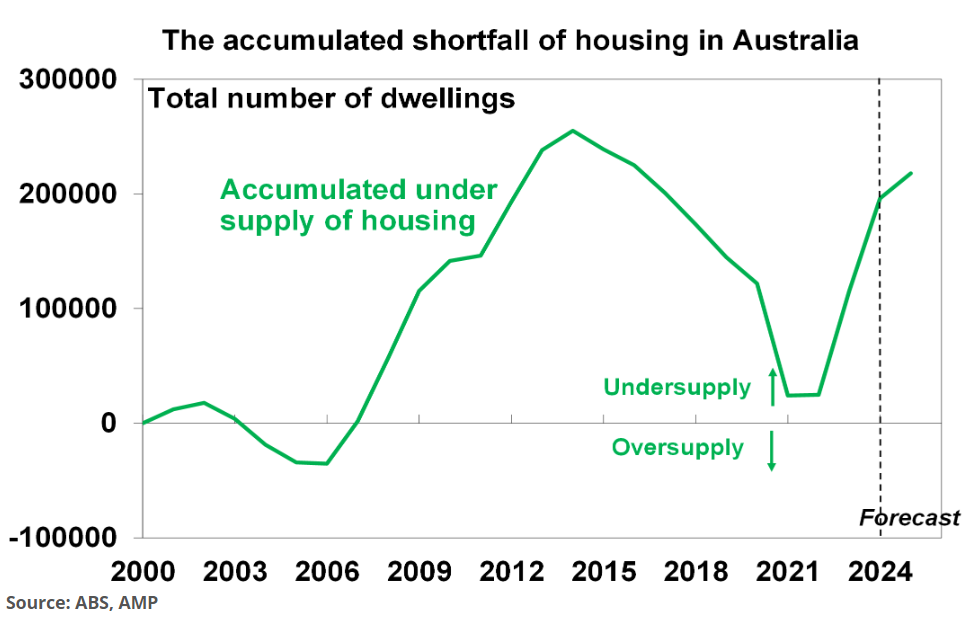

“On our estimates, the total accumulated number of dwelling undersupply is around 200K dwellings nationally which is around 78K households (based on the assumption that there are 2.5 persons per dwelling)”.

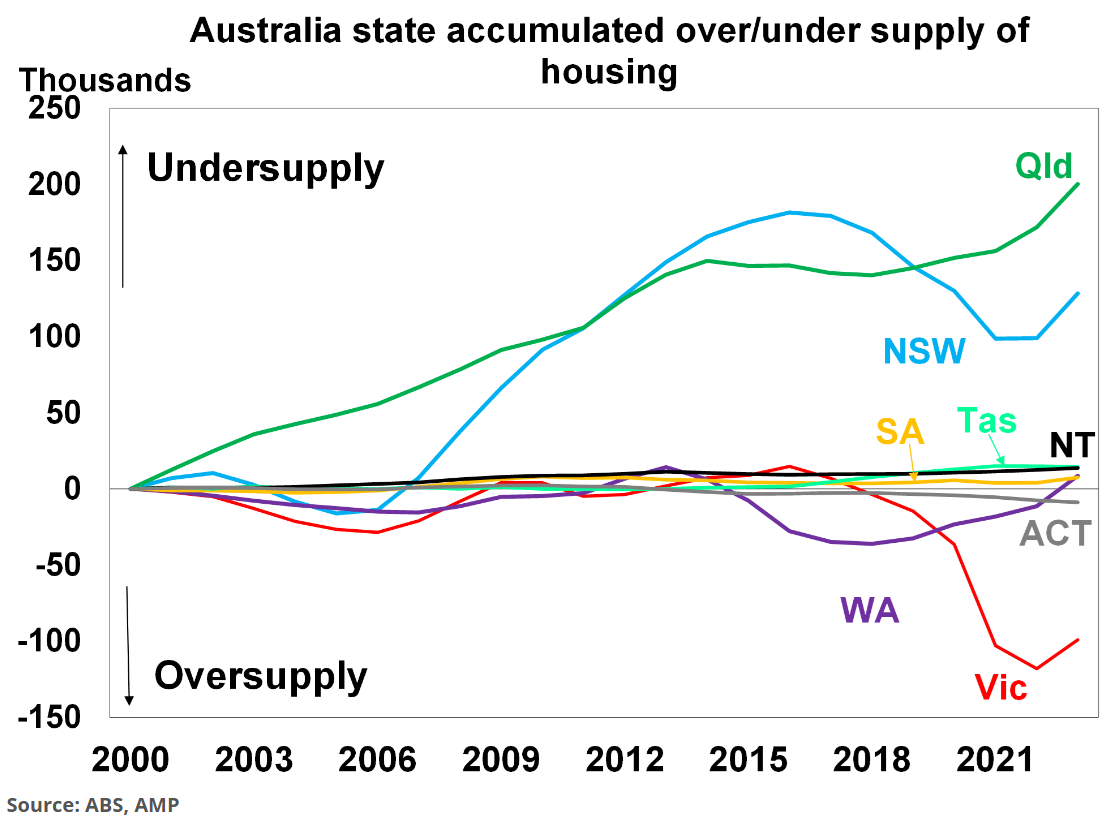

The next chart from AMP plots the estimated housing shortage across Australia’s states:

“Our findings show that the largest accumulated housing undersupply since 2000 is in Queensland and New South Wales, followed by Tasmania, the Northern Territory, Western Australia and South Australia”.

“But Victoria looks to be seeing a large oversupply of dwellings along with some oversupply in the ACT”.

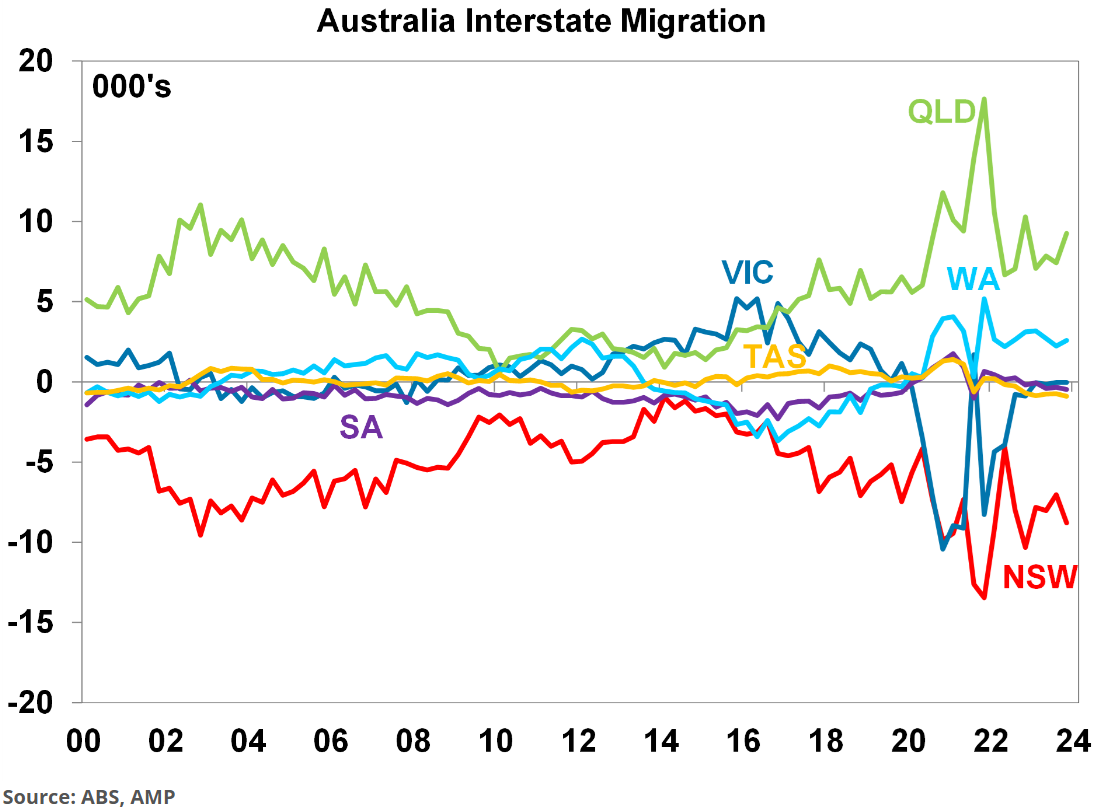

“Qld has experienced high interstate migration since 2018 (see the chart below) due to affordability challenges in neighbouring NSW, with the pandemic further increasing interstate migration into Qld”.

“Victorian housing completions have run at high levels relative to other states in recent years and the outflow of interstate migration during the pandemic (see the chart below) deepened the oversupply”.

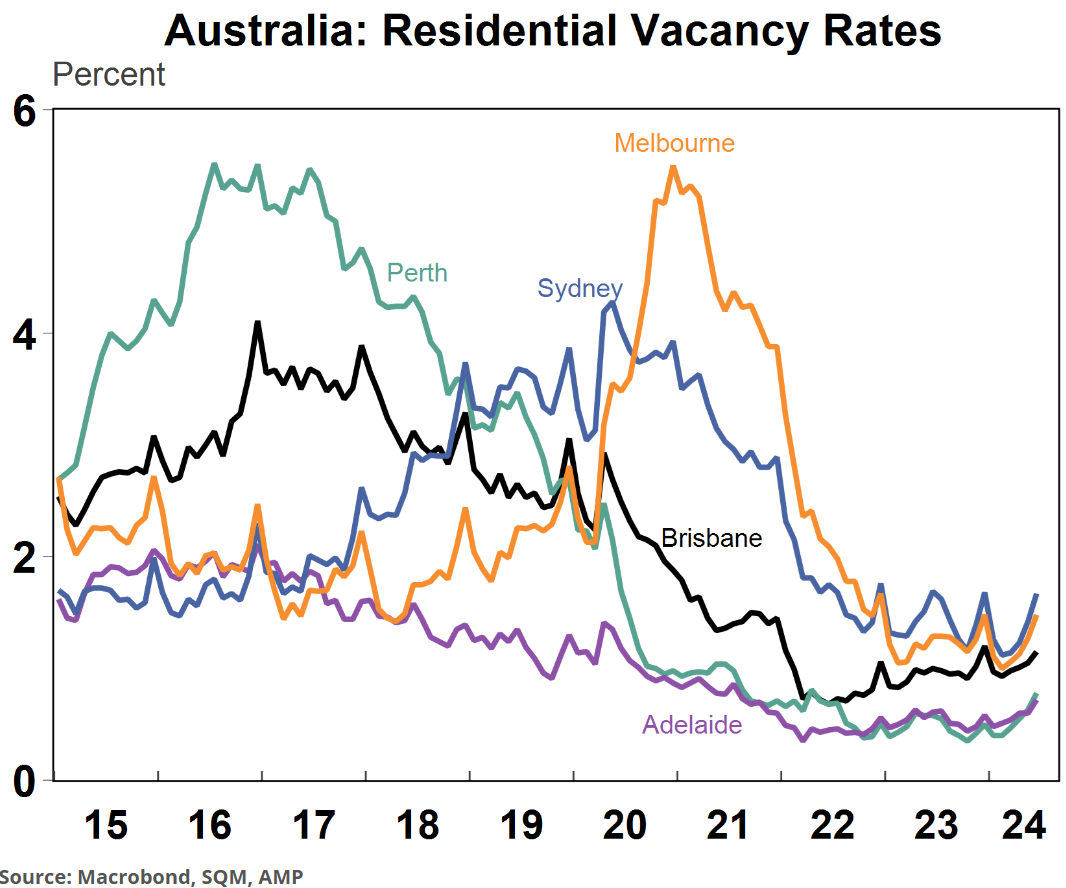

However, Mousina then contradicts herself somewhat with the next chart showing rental vacancy rates plummeting across each of the major capitals, which suggests that Victoria is badly undersupplied as well:

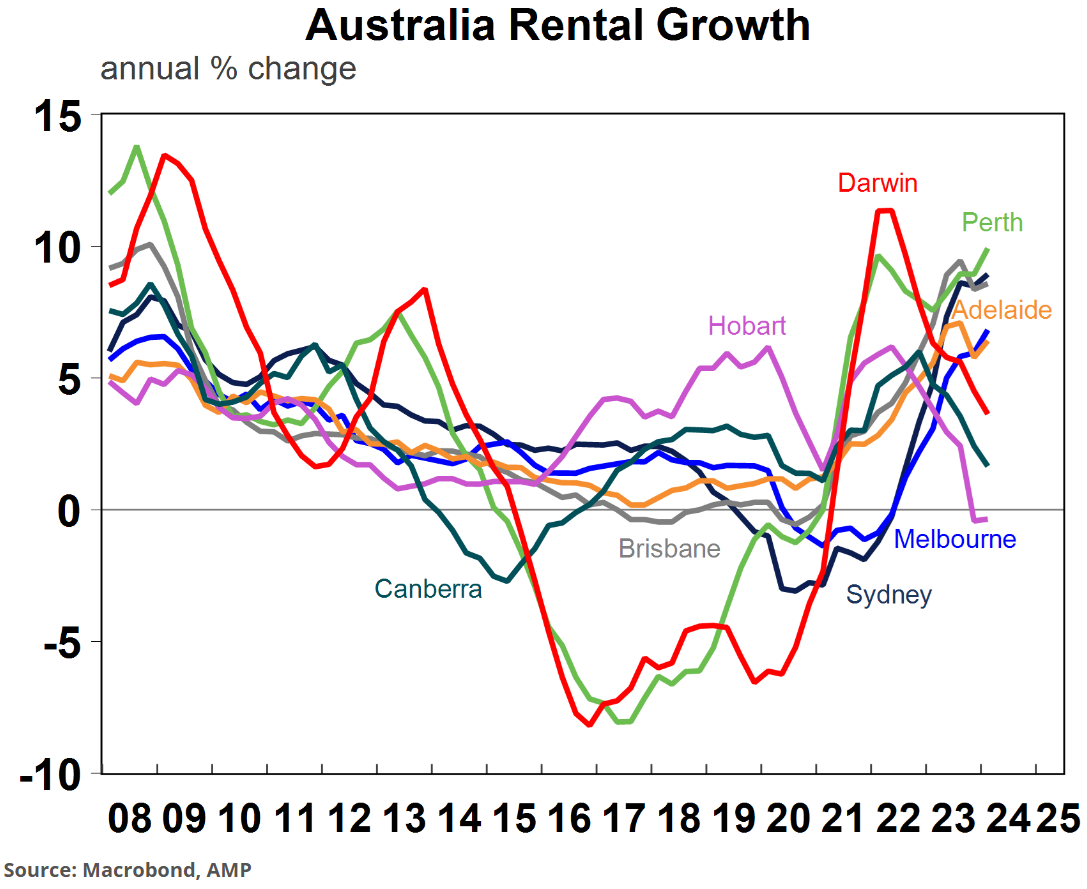

In a similar vein, rental growth has been universally strong across each of the major capitals, suggesting a universal shortage across these markets:

These minor contradictions aside, Mousina’s overall conclusion is correct:

“Fundamentally, Australia is not building enough homes to keep up with demand which is putting upward pressure on home prices and rents”…

“However, based on current levels of building approvals, issues with labour shortages and high material costs we think that construction levels will remain below underlying demand and keep upward pressure on home prices for some time yet”.

Mousina also labelled the Albanese government’s 1.2 million housing target as “aspirational” and unlikely to be achieved.

The only viable solution, therefore, is to cut demand by slashing net overseas migration to a level that is below the nation’s ability to build housing and infrastructure.