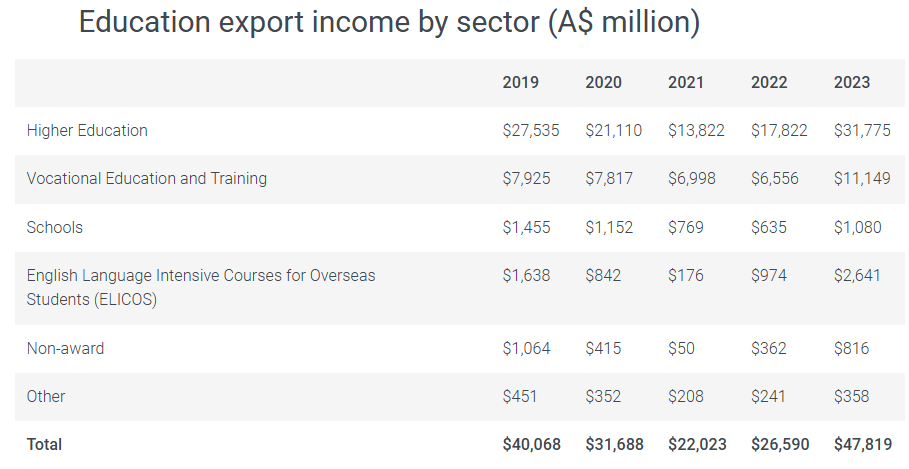

Last week, I provided evidence that the famed $48 billion of international education exports were a statistical con.

Source: Department of Education

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) calculates this fantastical export figure by combining “an average spend estimate from Tourism Research Australia … supplemented by the addition of the total expenditure on course fees”.

The ABS incorrectly classifies all spending by international students as exports, even when the expenditures are paid for with Australian-earned money.

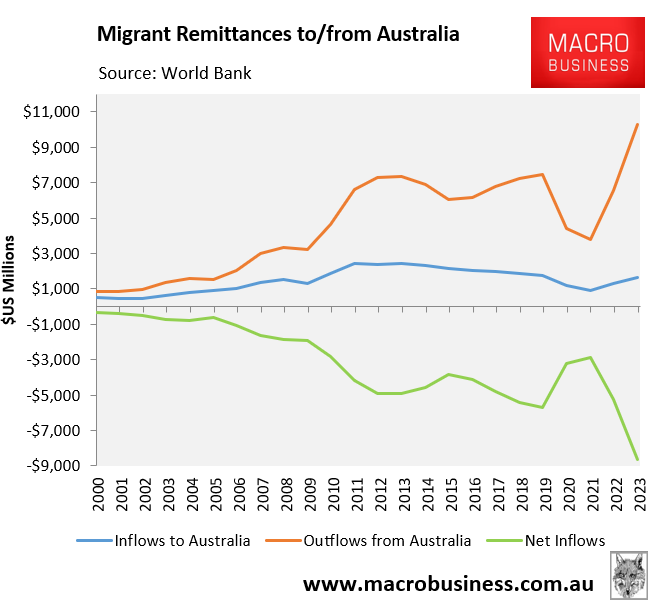

The following chart shows World Bank data on migrant remittances to/from Australia:

In 2023, migrant remittance inflows into Australia were only valued at $US1.6 billion, whereas outflows were valued at $US10.3 billion, giving a record net outflow of $US8.6 billion.

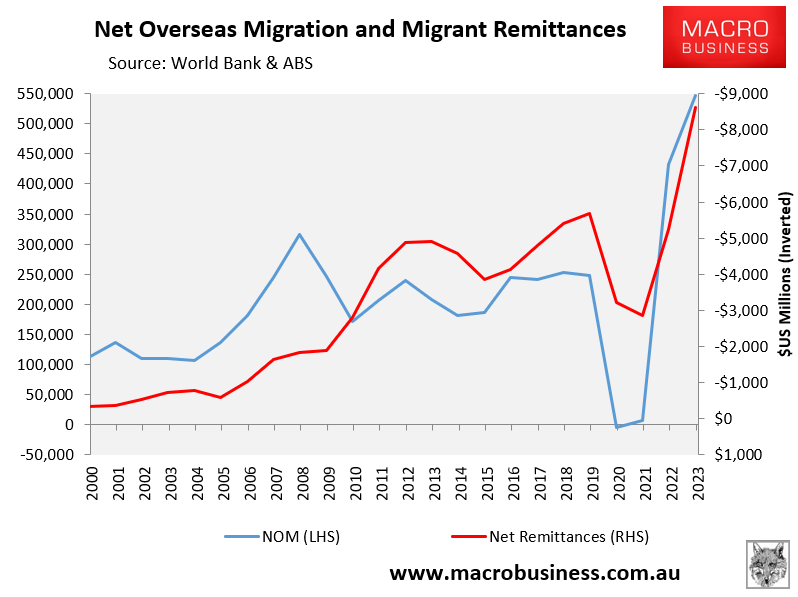

The net outflow in migrant remittances has also tracked net overseas migration:

As net overseas migration increased, so did the outflow of migrant remittances.

The ABS’s reported $48 billion education export figure is a hoax. Otherwise, why would Australia have sent a net $US8.6 billion in migrant remittances to other countries in 2023?

If the ABS’ education export figure were accurate, Australia would have seen a strong net inflow in migrant remittances.

The truth is that the overwhelming majority of expenditure in Australia by international students is funded by them working in Australia.

Judging by the remittance charts above, international education is more likely to be an import, as migrants send money from Australia to their home countries.

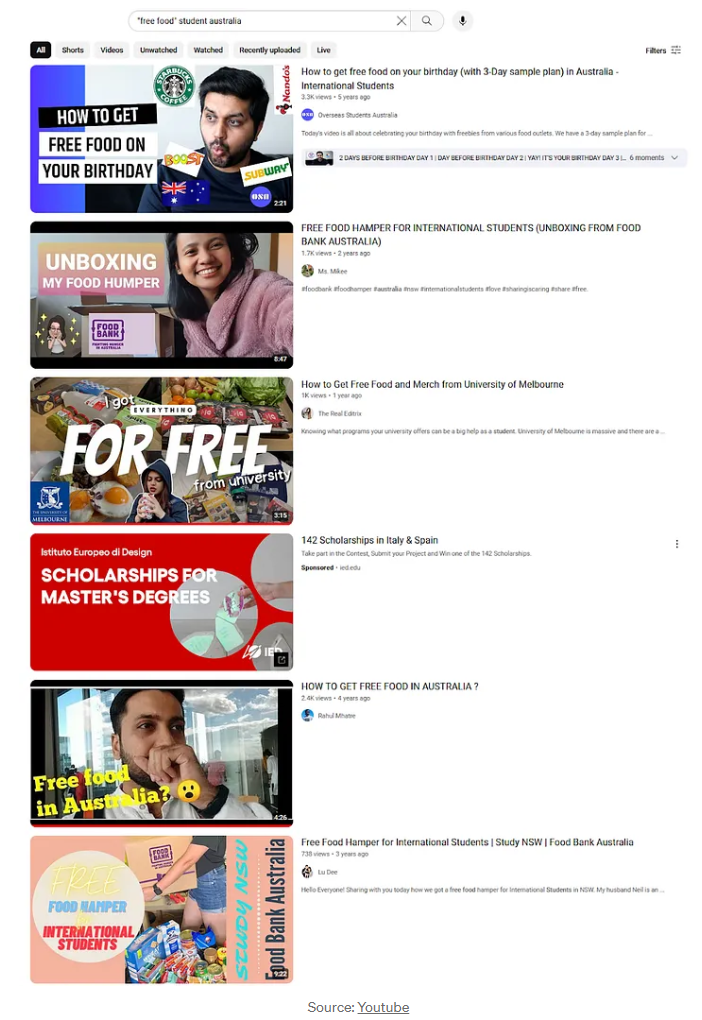

In his latest magnum opus on Australia’s political economy, Matt Barrie also noted that “YouTube and Tiktok are full of videos from international students explaining how to rort free food out of the system:

“I’m not sure why we’re providing visas for international students who can’t afford to feed themselves”, Barrie wrote.

“This is supposed to be an “export” not a humanitarian program”.

Indeed, ACA ran the below report on the proliferation of people turning to food banks in Melbourne:

The reporter noted that “the line is full of students” before interviewing a foreign student who remarked, “This [food bank] is good. This is very helpful for us for international students”.

In a similar vein, the Herald-Sun last year reported that demand for free food services and food banks had soared across Melbourne’s universities, with 85% of this demand coming from international students.

Victoria University Student Union president Chandra Altoff claimed that international students were heavily impacted by the rising cost of living and received little welfare support.

“We can grab five basic items, such as rice, milk, pasta, tomato sauce, soup – it’s a lifesaver”, international student Krithika Venkatanath said, while admitting that she used the free food service most days.

“It’s so hard to juggle work and study, especially with the upfront costs and higher tuition fees for international students”, she said.

Krithika Venkatanath, 24, is an international student at Swinburne and regularly uses Foodbanks. Source: Herald-Sun.

While we sympathise with Ms Venkatanath’s situation, what use is having international education “exports” who are the working poor?

Ms Venkatanath must work to cover her living expenses, competing with younger Australians for jobs and relying on charitable services to survive.

When international students become a drain on charitable services, then the economic and human value to Australia turns negative.