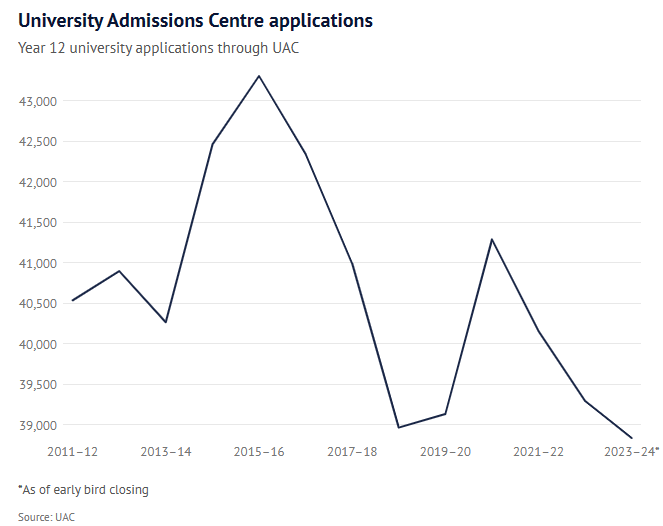

In December 2023, The SMH reported that year 12 applications to the University Admissions Centre (UAC) hit their lowest in over a decade:

The general manager of marketing and engagement at UAC, Kim Paino, noted that the high cost of living, a robust job market, and rising costs of higher education were likely to blame for the softening of demand.

Department of Education data also showed that new students, primarily made up of high-school leavers, slumped to 267,110 from 290,900 in 2021, representing the smallest cohort since 2013.

The overall number of Australians studying a university course in 2022 also fell to 1.1 million, down by 60,000 or 5.1% on the previous year, suggesting that young people are shunning degrees.

According to Andrew Norton at the ANU, it was the first time since the 1950s that university enrolments were going backwards.

I can’t blame young Australians for avoiding university, given that degrees have lost much of their worth.

While university degrees can help you find a job, they do not guarantee success, according to a study by the Mackenzie Research Institute at the Holmesglen Institute in Melbourne, which was based upon data from the 2011 and 2021 Australian censuses.

Although people with a university education are more likely to hold the highest-paying and most prestigious jobs, their share of low-wage occupations is also increasing.

This frequently results in the displacement of individuals with only diplomas and trade certificates, who replace those with little or no further education.

Over the decade to 2021, the share of people with postgraduate degrees in the labour force increased from 5% to 9%, while the number of such graduates more than doubled, from roughly 500,000 to nearly 1.1 million.

Currently, around 3.1 million Australians hold undergraduate degrees, accounting for more than one-quarter of the total Australian work force.

In 2021, about 2% of labourers, machine operators, and technicians, 3% of salespeople, and 6% of clerical and administrative workers held master’s or doctoral degrees.

Each of these fields had around four times the number of people with bachelor’s degrees.

“Credentials are becoming increasingly important even in lower paid jobs”, noted study author Dr. Tom Karmel, former executive director of the National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

“Is it skills deepening or is it really just blatant credentialism? It’s probably a bit of both. If everybody had a degree, a degree would be useless”.

“It makes me think that maybe we have reached peak higher education,” said Peter Hurley, director of the Mitchell Institute at Victoria University.

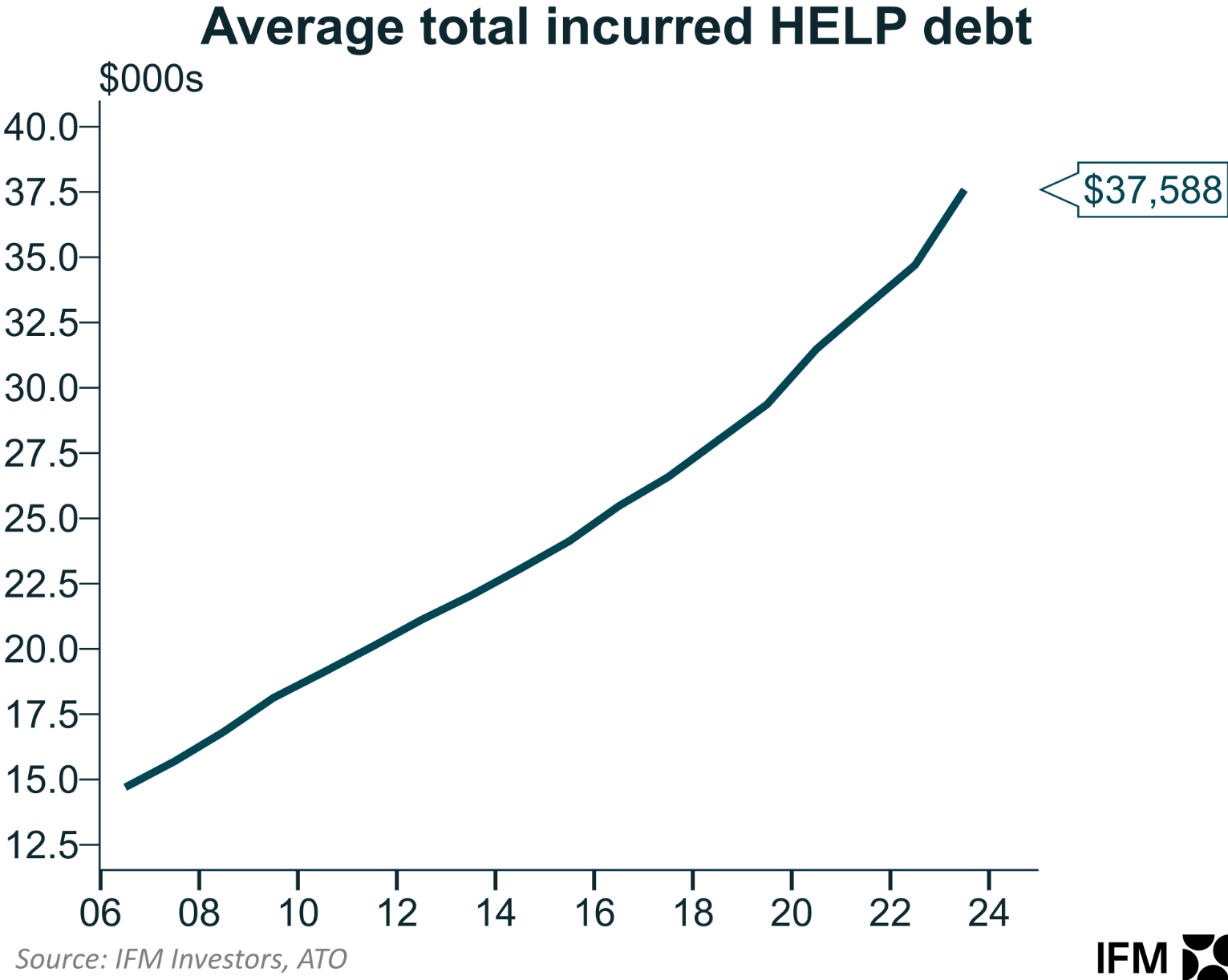

Meanwhile, the cost of studying at university continues to balloon.

As the following chart from Alex Joiner at IFM investors shows, the average HELP debt has risen to $37,588:

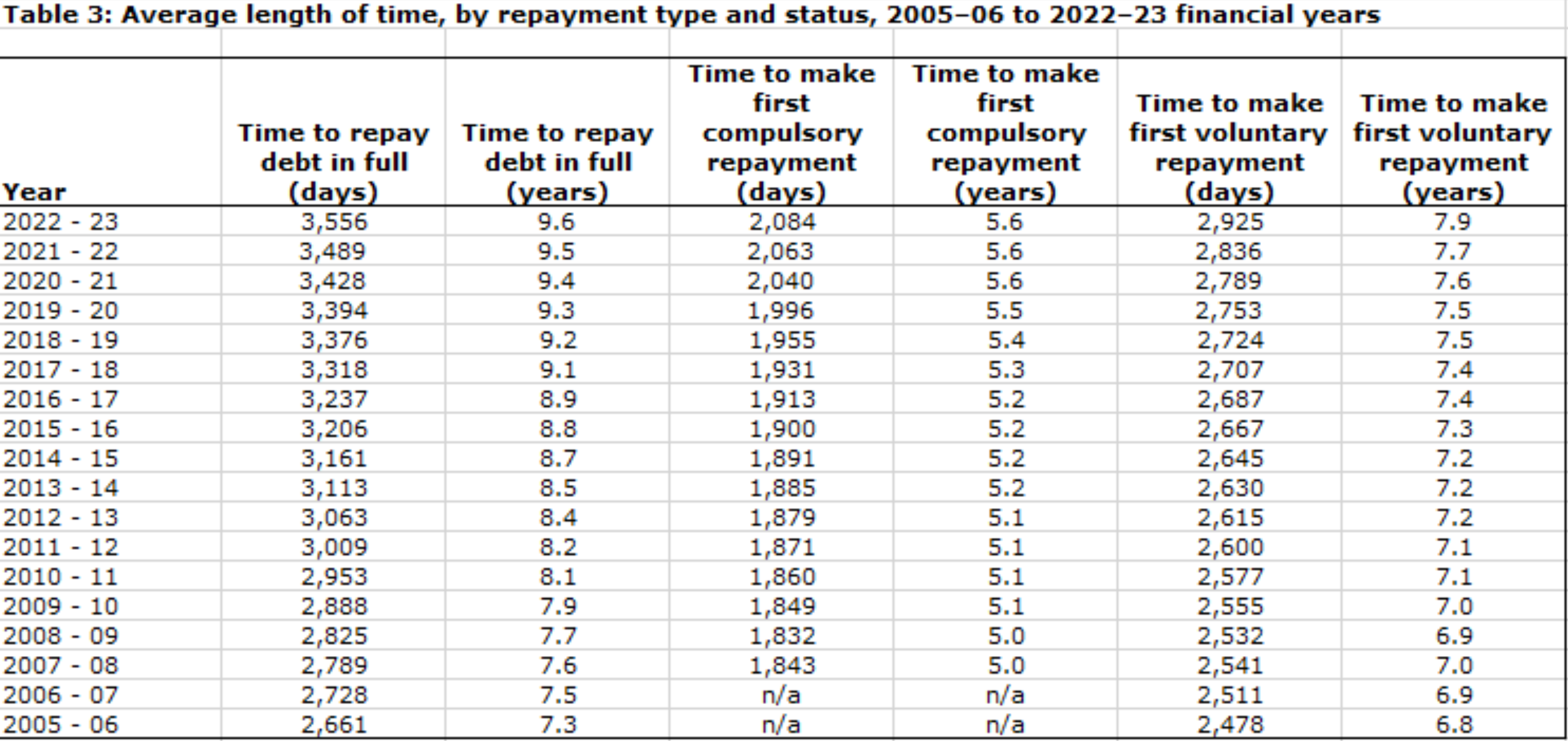

It also takes borrowers around a decade to pay off their university debts:

As reported in The Guardian, “Arts degrees in Australia are set to cost more than $50,000 for the first time, with experts warning some students will never be able to pay off their debts under the current system”.

“The new figure places Australia on par with the UK and public colleges in the US”…

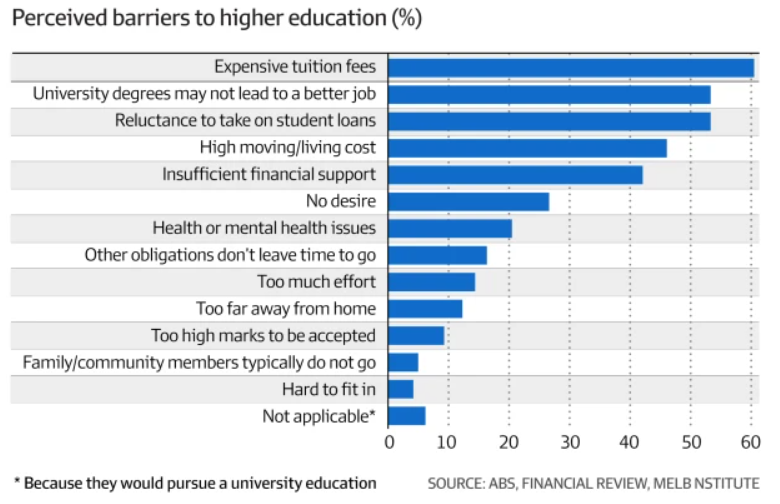

A recent Melbourne Institute Taking the Pulse of the Nation survey revealed that 52% of respondents believed that going to university would not lead to better employment opportunities, while the same proportion believed that having too much student debt was a barrier. Both those who had earned degrees and those who had never gone shared these opinions.

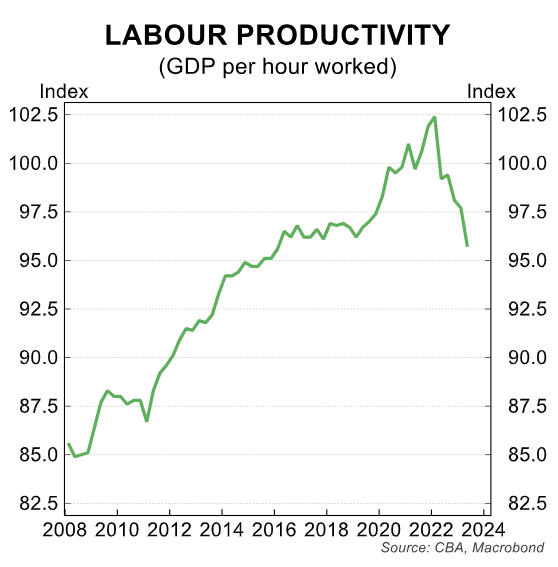

One of Australia’s most perplexing economic paradoxes is that, despite having a huge number of university graduates in the labour market, the country suffers from low productivity growth and “skills shortages” that never ease.

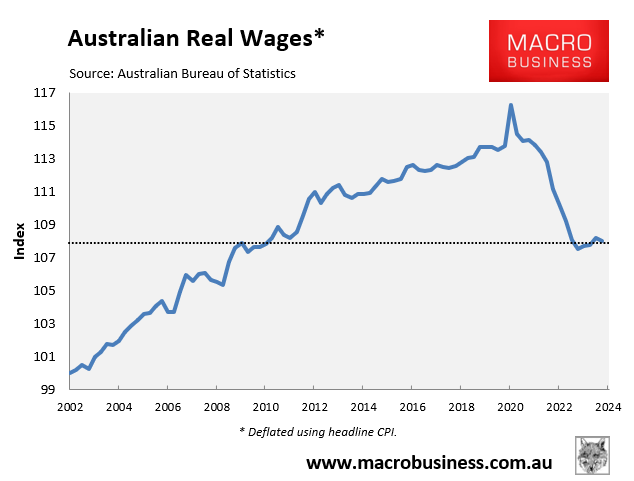

Australia has also suffered from declining real wages at the same time as the number of university qualified graduates has ballooned:

Despite these inconvenient truths, the Albanese government’s Universities Accord has set a higher education attainment target of 55% by 2050. This would result in an additional 300,000 domestic undergraduate student enrolments by 2035 and 900,000 by 2050.

Why does the Albanese government desire 55% of Australians aged 25–44 to hold a bachelor’s degree or higher?

The majority of employment in Australia requires a university degree, not because of any specific skill requirement or demand, but rather as a lazy “signalling” technique employed by employers to select job candidates.

This “credential inflation” has raised university enrolments while having no beneficial economic or societal impact.

The value of a university degree has decreased as the number of people pursuing higher education has grown to the point where too many people now have a degree.

The current situation is absurd because entry-level positions that were previously open to those with only a high school diploma now require a university degree.

Meanwhile, public funding has been moved away from TAFE and vocational education, which have declined in popularity. This has resulted in recurrent skill shortages in a wide range of occupations, most notably the trades.

Universities have degraded into profit-driven parasites, graduating far too many students who would have benefited more from a vocational program.

Australia’s focus on higher education must change.

First and foremost, university admissions requirements should be more stringent for both domestic and international students. Governments should also increase VET and TAFE funding.

Prioritising universities above vocational or trade schools was never in Australia’s best interests, either socially or economically.