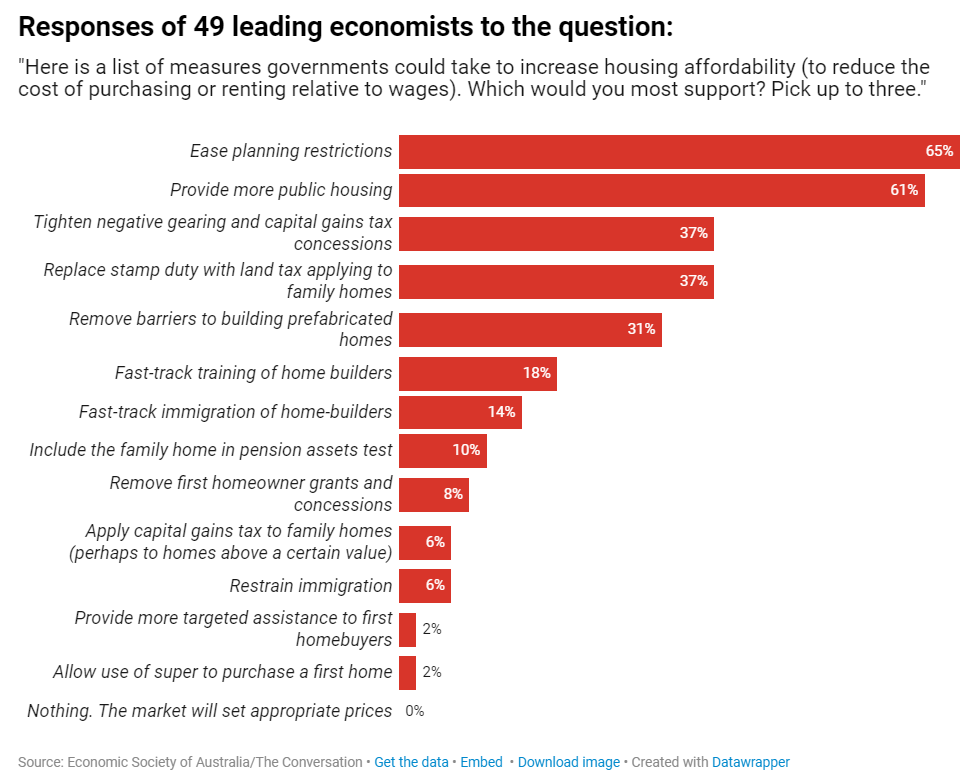

Last week’s survey of 49 “leading” economists blamed a lack of supply for Australia’s housing crisis while denying that two decades of excessive demand via record immigration have played a material role.

Note from the above graphic that only 6% of surveyed economists picked “restrain immigration” as a solution to Australia’s housing mess, while 14% picked “fast-track immigration of home”builders”—effectively importing migrants to build homes for migrants.

The gaslighting on Australia’s housing crisis continued with the release of two housing reports from Everybody’s Home and the Blueprint Institute, which explicitly denied that excessive levels of immigration have played a meaningful role in the housing crisis.

According to Everybody’s Home’s report:

Migration is often wrongly attributed as a primary driver of Australia’s housing crisis, despite evidence to the contrary.

Many migrants join existing households, while international students are much more likely to live in dedicated student accommodation, which is not consistently counted in dwelling numbers. More generally, the number of homes per person in Australia has been consistently rising for decades, indicating that the overall housing stock has grown in proportion to population.

However, ongoing perceptions that international migrants have caused a housing shortage, is undermining the social licence for migration.

And here’s the Blueprint Institute’s drivel:

While it is true that Australia’s net migration spiked in response to the reopening of borders after the COVID shutdown, it is unhelpful to suggest that putting blunt restrictions on immigration will solve the housing crisis.

Historic undersupply has meant that the housing market has been unable to cope with this recent spike in migration, even though the total population increase has been minimal.

This is less a reflection on the state of immigration, and more on the state of our housing supply—the majority of migrants entering Australia will be younger and more likely to live in larger households than the average Australian, and are thus more likely to live in space efficient dwellings.

First, the claim that “the total population increase has been minimal” since the start of the pandemic is a bald-faced lie.

Australia’s population was 25,520,500 as at 31 December 2019. It is currently 27,402,000 according to the ABS’ Population Clock.

This means that Australia’s population has swelled by 1,881,500 in just over 4.5 years, meaning the population has increased at an annual rate of around 415,000 people per year. That is almost the equivalent of growing by a Canberra’s worth of people every year.

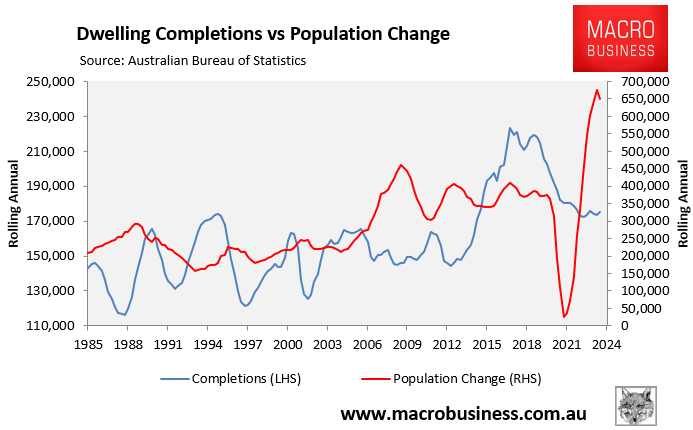

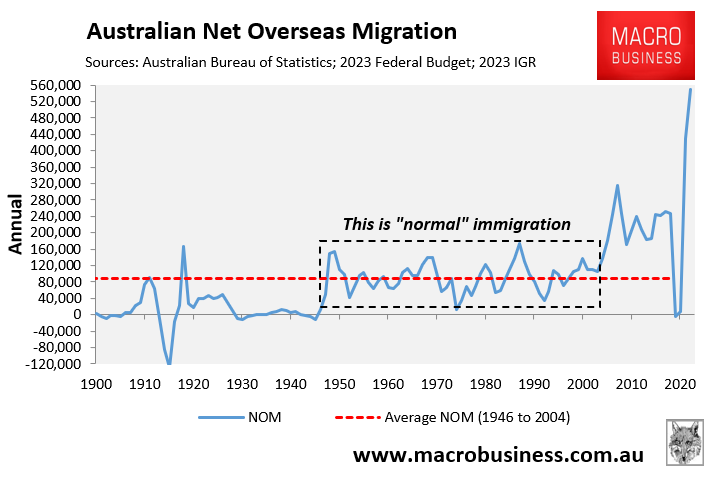

Second, the growth in Australia’s population since immigration was more than doubled in the mid-2000s has been extreme and has overwhelmed the supply-side of the housing market:

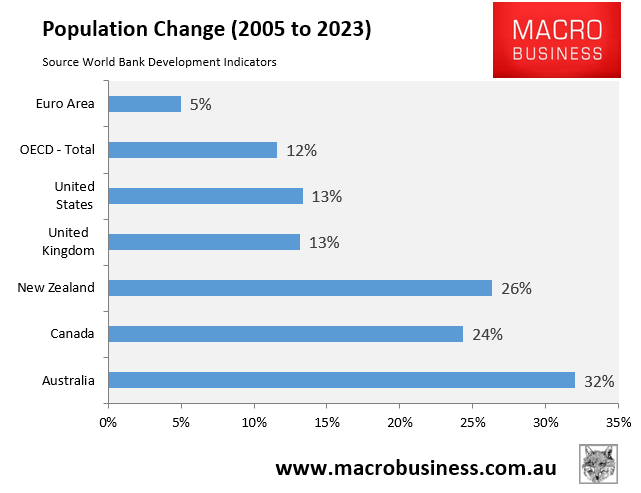

This increase in immigration meant that Australia experienced the strongest population growth over the past two decades among major developed nations:

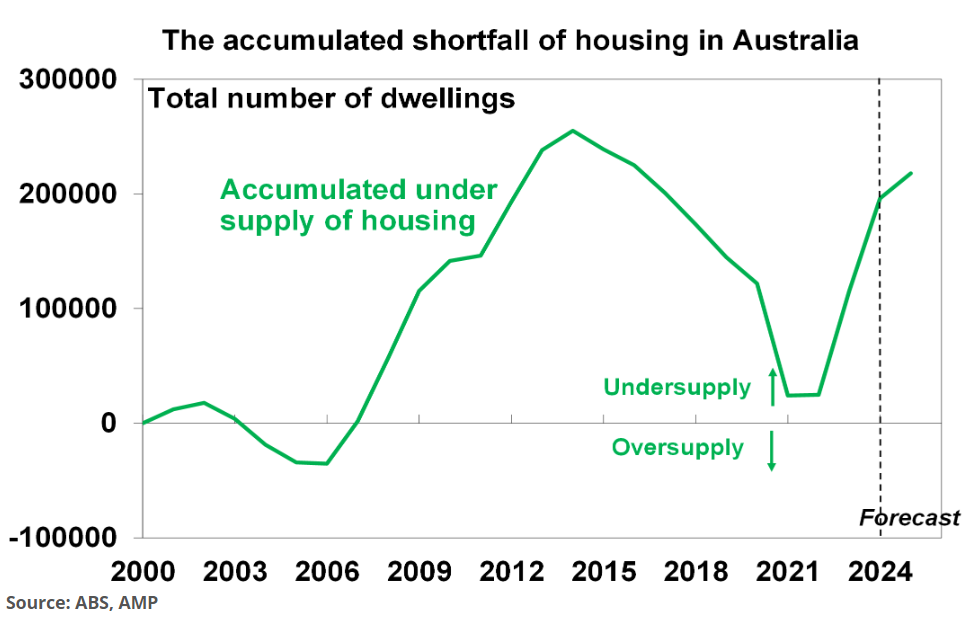

Population demand exceeded housing supply, resulting in a structural shortage of housing:

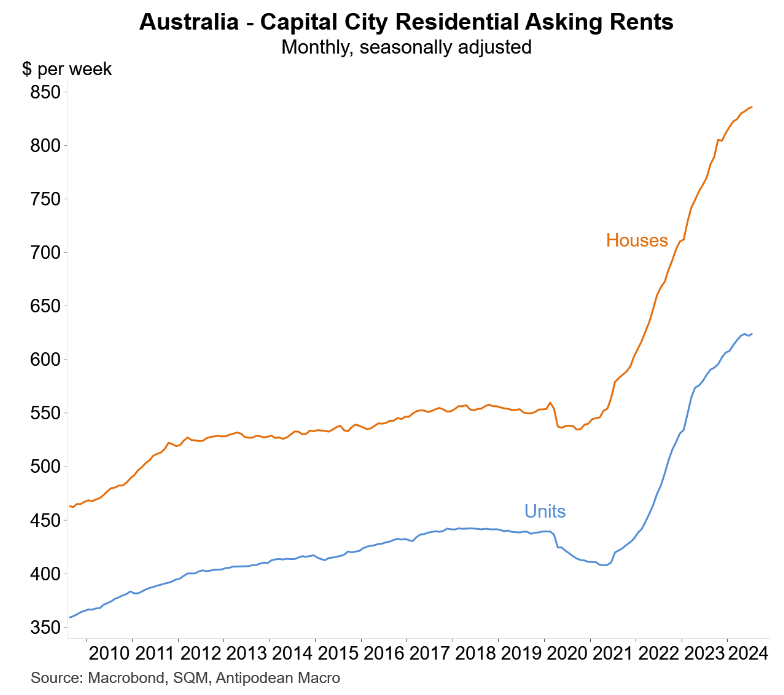

This shortage was nearly eliminated during the pandemic when net overseas migration briefly turned negative, only to emerge with gusto once immigration shot to record levels amid sluggish construction, driving-up rents:

The reality is that Australia will struggle to build enough housing as long as its population continues to grow rapidly through net overseas migration.

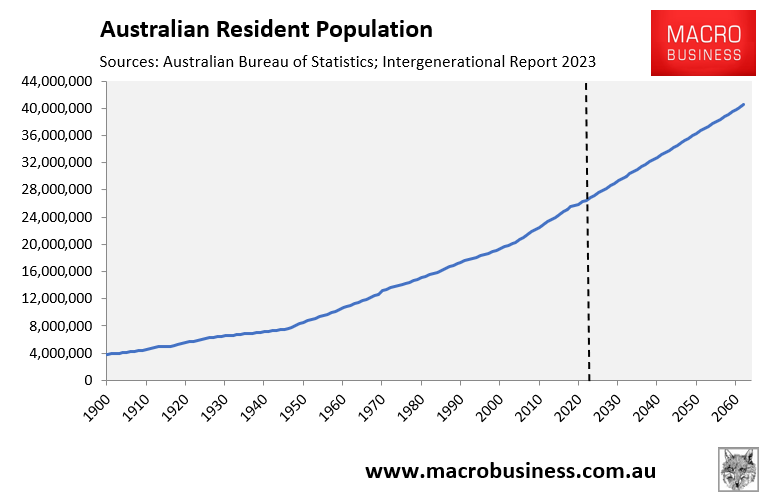

The most recent Intergenerational Report estimated that Australia’s population would swell to 40.5 million by 2062-63:

If this estimate comes true, Australia’s population will grow by 13.5 million in just 39 years, which is equivalent to adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the country’s existing population.

This level of population growth would conservatively require the construction of around 6 million homes, allowing for demolitions.

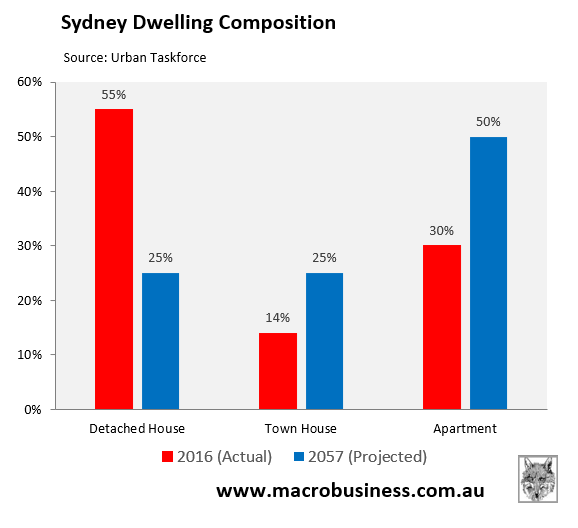

I say conservative because the majority of these residences would be apartments, which by definition cannot accommodate as many people as detached homes.

An additional 13.5 million people would also require significant infrastructure construction, which would continue to compete with housing for labour and resources.

Australia’s economists and housing analysts should cease gaslighting and recognise that reducing immigration to a level below the country’s capacity to supply homes and infrastructure is a key solution to the housing crisis.

The truth is staring them in the face.