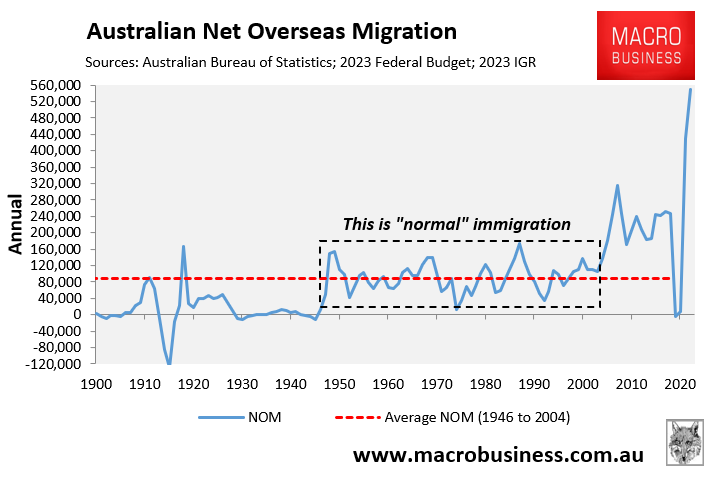

Politicians, think tanks, vested interests, and the media frequently spread the myth that high levels of immigration are necessary to raise productivity and living standards in Australia.

Yet, the actual lived empirical evidence shows the opposite, with Australian productivity and living standards eroding over the past 20 years of ‘Big Australia’ immigration.

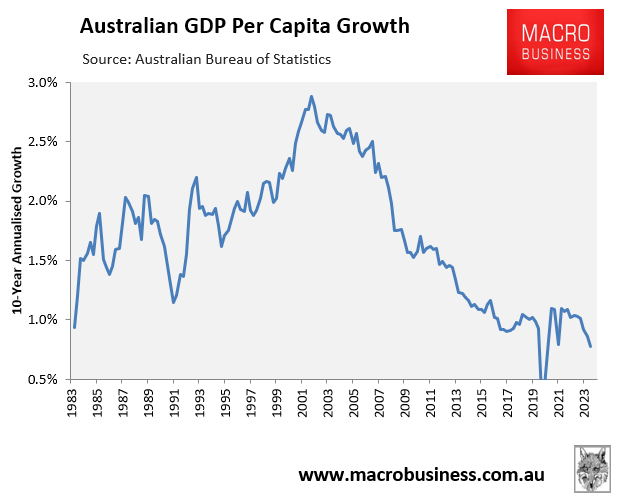

Reflecting poor productivity, Australia’s per capita GDP growth collapsed after net overseas migration was more than doubled in the mid-2000s.

Meanwhile, housing has become smaller and more expensive and infrastructure has become increasingly overburdened and congested.

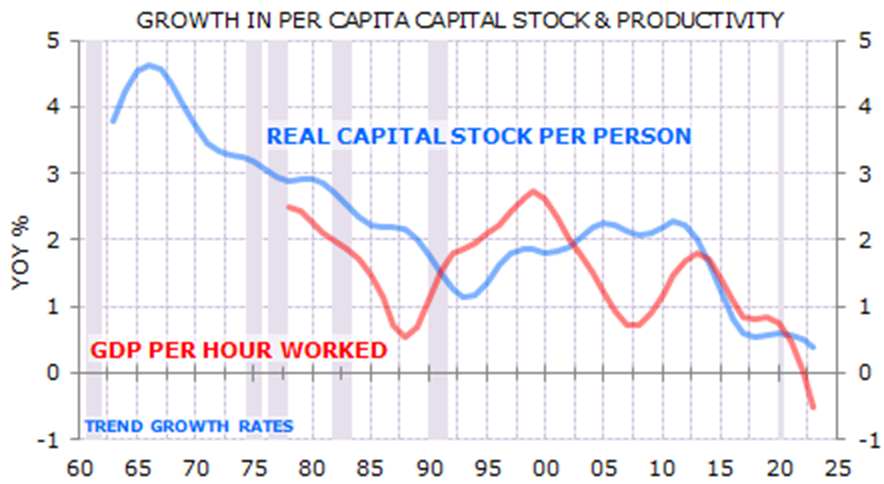

Indeed, the collapse in Australia’s productivity and per capita GDP growth can be attributed, at least in part, to “capital shallowing”, which has occurred because Australia’s population has grown faster than business, infrastructure, and housing investment.

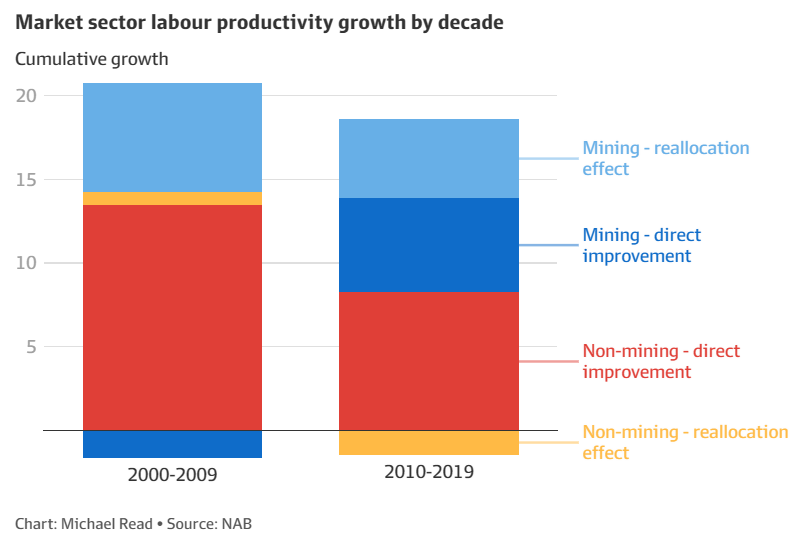

The following chart from NAB is instructive. It shows that non-mining business investment collapsed last decade at the same time as Australia’s population ballooned due to high net overseas migration:

Similar occurred with respect to infrastructure investment.

Gerard Minack described Australia’s capital shallowing as follows:

Australia’s economic performance in the decade before the pandemic was, on many measures, the worst in 60 years.

Per capita GDP growth was low, productivity growth tepid, real wages were stagnant, and housing increasingly unaffordable.

There were many reasons for the mess, but the most important was a giant capital-to-labour switch: Australia relied on increasing labour supply, rather than increasing investment, to drive growth.

Australia’s population-led growth model was a demonstrable failure in the 15 years prior to the pandemic.

Remarkably, the country now seems to be doubling down on the same strategy. The result, unsurprisingly, is likely to be more of the same.

Canada adopted the same immigration-driven economic model with similar results.

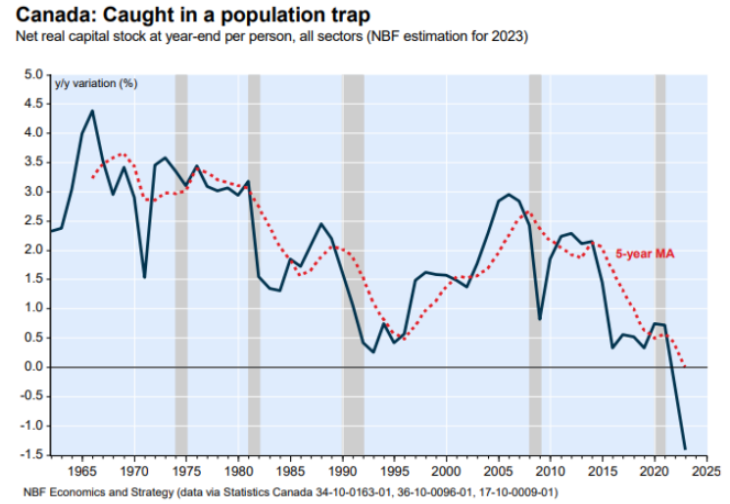

High immigration meant that Canada’s population grew faster than business, infrastructure, and housing investment, diluting the country’s capital base:

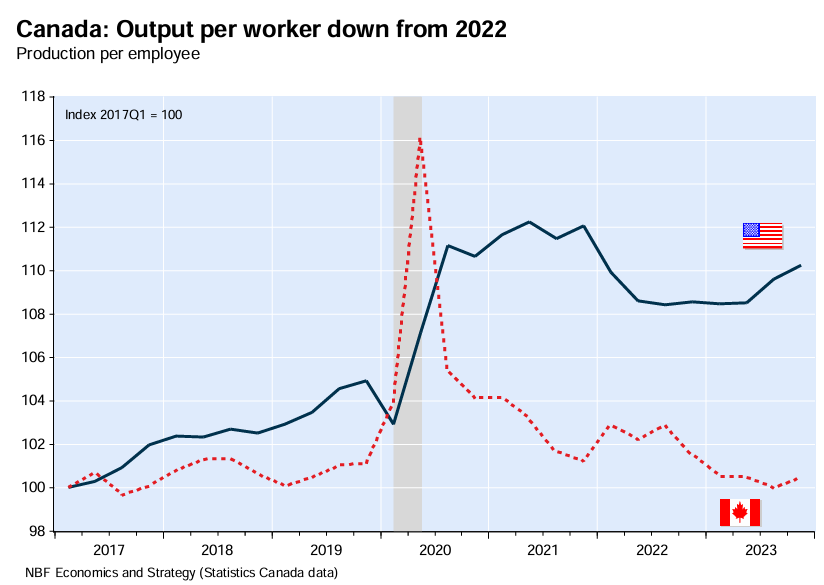

As a result, Canada’s productivity growth has been appalling:

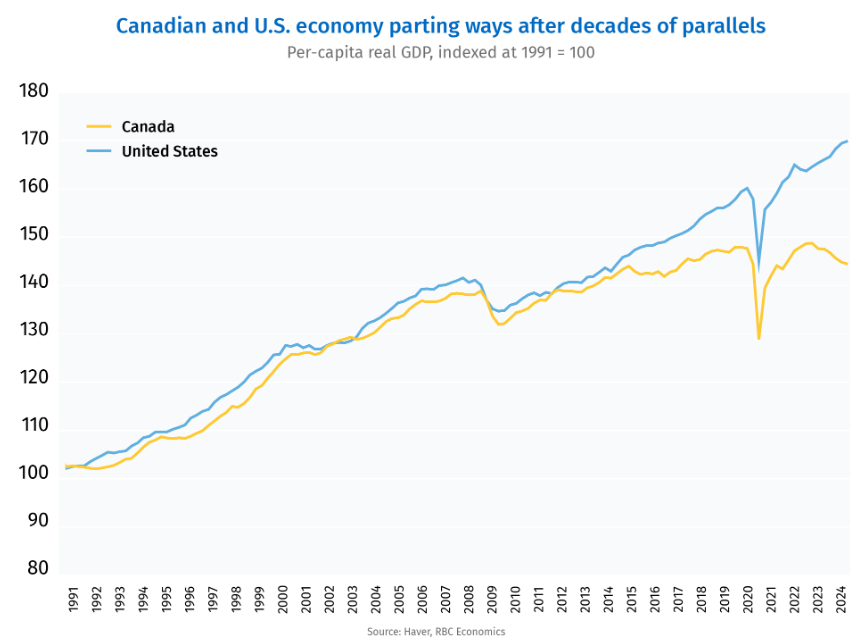

And Canada’s GDP per capita has flatlined:

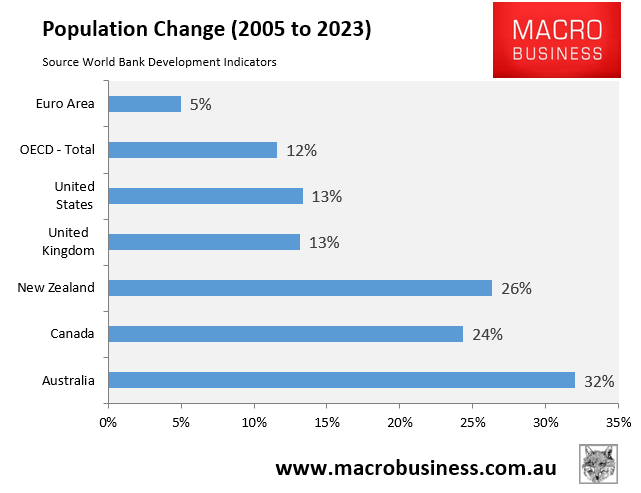

You can also add New Zealand into the mix, which has more or less copied Australia’s and Canada’s high immigration strategies.

All three nations have experienced far stronger population growth since 2005 than other developed nations:

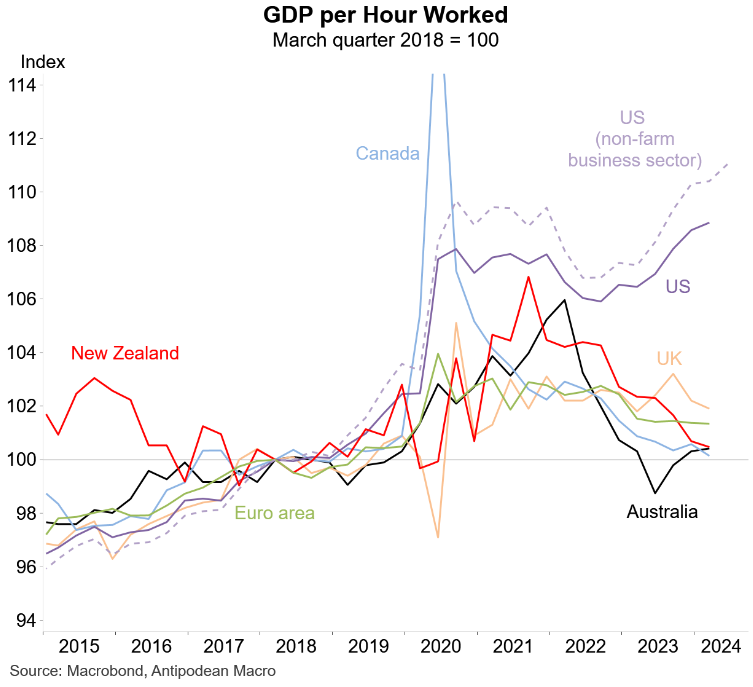

Now look at the following chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro plotting labour productivity across developed nations:

As you can see, New Zealand, Canada, and Australia have experienced the poorest labour productivity since 2015.

Surely the above chart flies in the face of claims that high immigration boosts productivity and living standards?

Because the empirical evidence and lived experience continue to show the opposite, due at least in part to the capital shallowing effect.