Earlier this week, The Guardian’s education editor, Caitlin Cassidy, threw a grenade into Australia’s higher education industry with an article exposing universities for handing out prestigious degrees to international students who cannot speak basic English and do not understand the course content.

Following the publication of the article, Cassidy stated on Twitter (X) that she had “received dozens of emails from former and current students, staff and academics about this article”:

Many people responded to her tweet with stories supporting the claims in the article. Below is an example:

Here is another from Dr Cameron Murray:

On Wednesday, Caitlin Cassidy followed up with a second hand grenade, exposing the corruption of the international education and university systems. This time, the focus was on systemic cheating.

Below are highlights from the article:

Australian academics say they are being pressured into passing hundreds of students suspected of plagiarism and other forms of cheating in order to maintain their universities’ revenue streams, threatening the integrity and international reputation of the entire sector…

“We’re not holding students to a standard,” she said. “It’s not fair on anyone who thinks a degree is worthwhile – a lot are not at the moment. It’s just proof they’ve been paid for”, [one tutor said]…

“Nobody is blind to it,” she said. “It’s not a social or educational environment; it’s a box-checking exercise. A master’s degree is not worth what a bachelor’s used to be.”

Up to 80% of her courses were composed of full fee-paying overseas students, she said. Many struggled with English language skills in classes and meetings yet produced perfectly written essays.

But she said she was unable to fail them…

“There was a near mutiny among the teaching staff when we were told that we had to mark [apparently] bot-written papers as if they had been written by students”, [another tutor said].

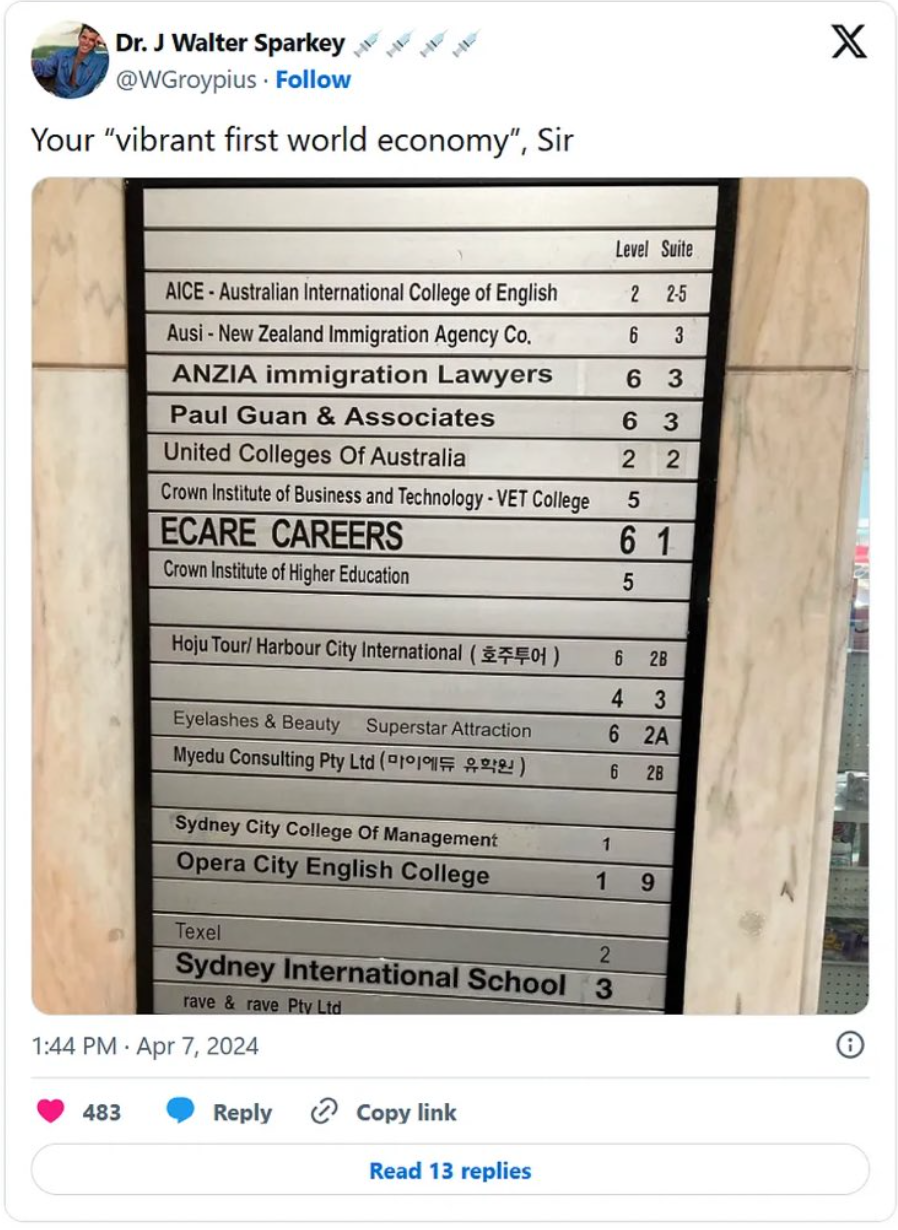

While the situation at universities is bad, spare a thought for private vocational colleges. Many of these are fraudulent “ghost colleges” set up purely as conduits for backdoor migration.

The fact that so many of these colleges have been allowed to operate for so long is evidence of corruption in plain sight.

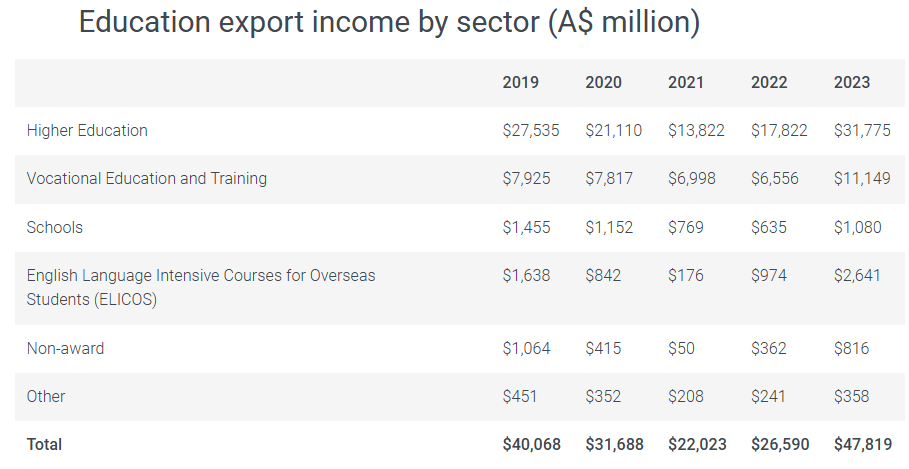

The widely quoted $48 billion in education exports is further evidence of corruption.

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) calculates education exports by combining “an average spend estimate from Tourism Research Australia … supplemented by the addition of the total expenditure on course fees”.

The ABS incorrectly considers any spending by a student visa holder as an export, even if the expenditure is paid with money earned while working in Australia.

Curiously, student visa holders are the only category of temporary migrants whose spending is classified as an export for the duration of their visa.

For example, if an international student Uber driver fills up with petrol in their fifth year of their visa, it is considered an export. However, if a newly arrived temporary migrant on a skilled visa fills up with petrol, it is not considered an export.

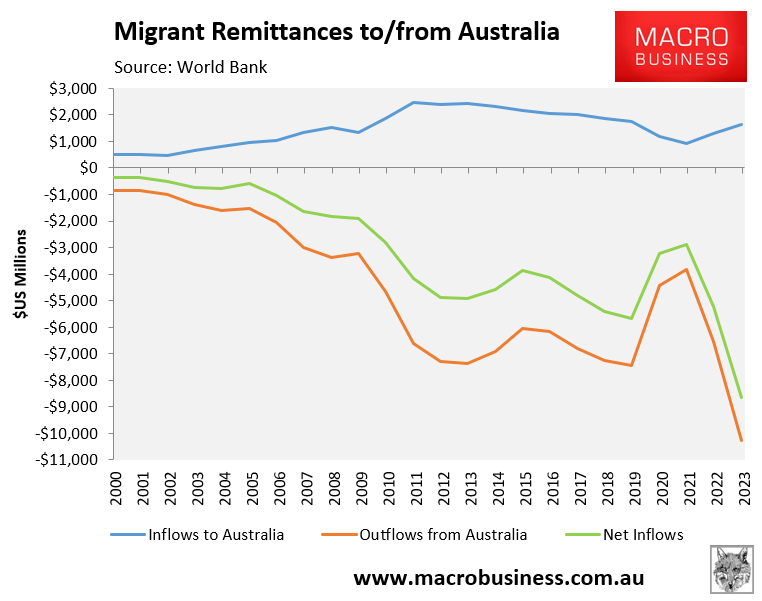

The World Bank’s migrant remittance statistics for Australia categorically refute the notion that international education is a significant export (or any export at all).

In 2023, migrant remittances to Australia totalled $US1.6 billion, a significant decrease from the peak of $US2.45 billion in 2011.

By contrast, migrant remittances from Australia totalled $US10.3 billion in 2023, resulting in a record net outflow of $US8.6 billion.

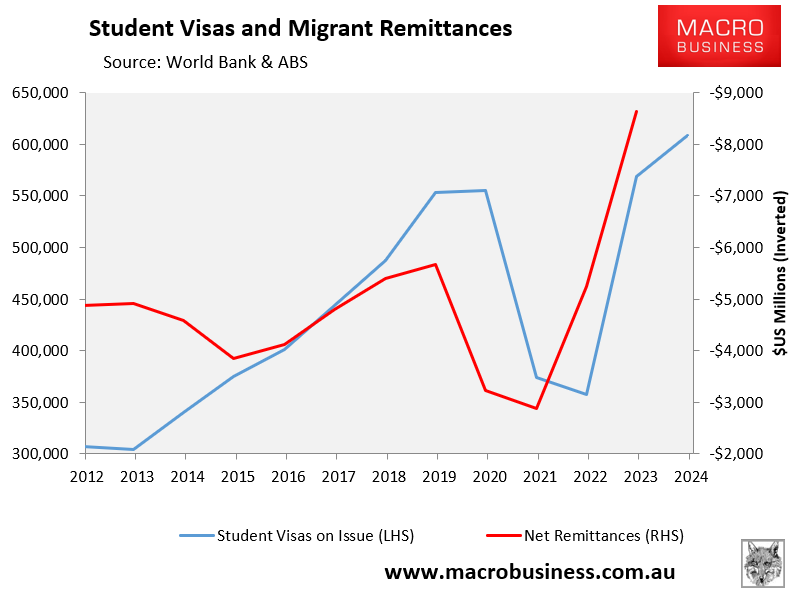

Unsurprisingly, the net outflow of remittances has roughly mirrored the increase in student visa holders:

Therefore, how can international education be deemed a massive $48 billion export industry when billions of dollars in net remittances flow out of Australia each year? Wouldn’t that suggest that it is an import?

I will believe that the federal government is serious about reforming international education when it does the following:

- Raises financial barriers to entry (i.e., how much funds a student must have available before arriving in Australia).

- Significantly increases entrance requirements (e.g., English language proficiency and academic testing).

- Raises pedagogical standards.

- Abolishes group assignments.

- Cuts the link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

- Requires universities to provide on-campus accommodation to international students in proportion to their enrolments.

Australia must aim for a smaller cohort of high-quality students, focusing on quality over quantity.

Then, international education may become a genuine export industry that adds value to Australia.