The last few years have been a difficult time for Australia’s rising army of renters, particularly those on lower incomes.

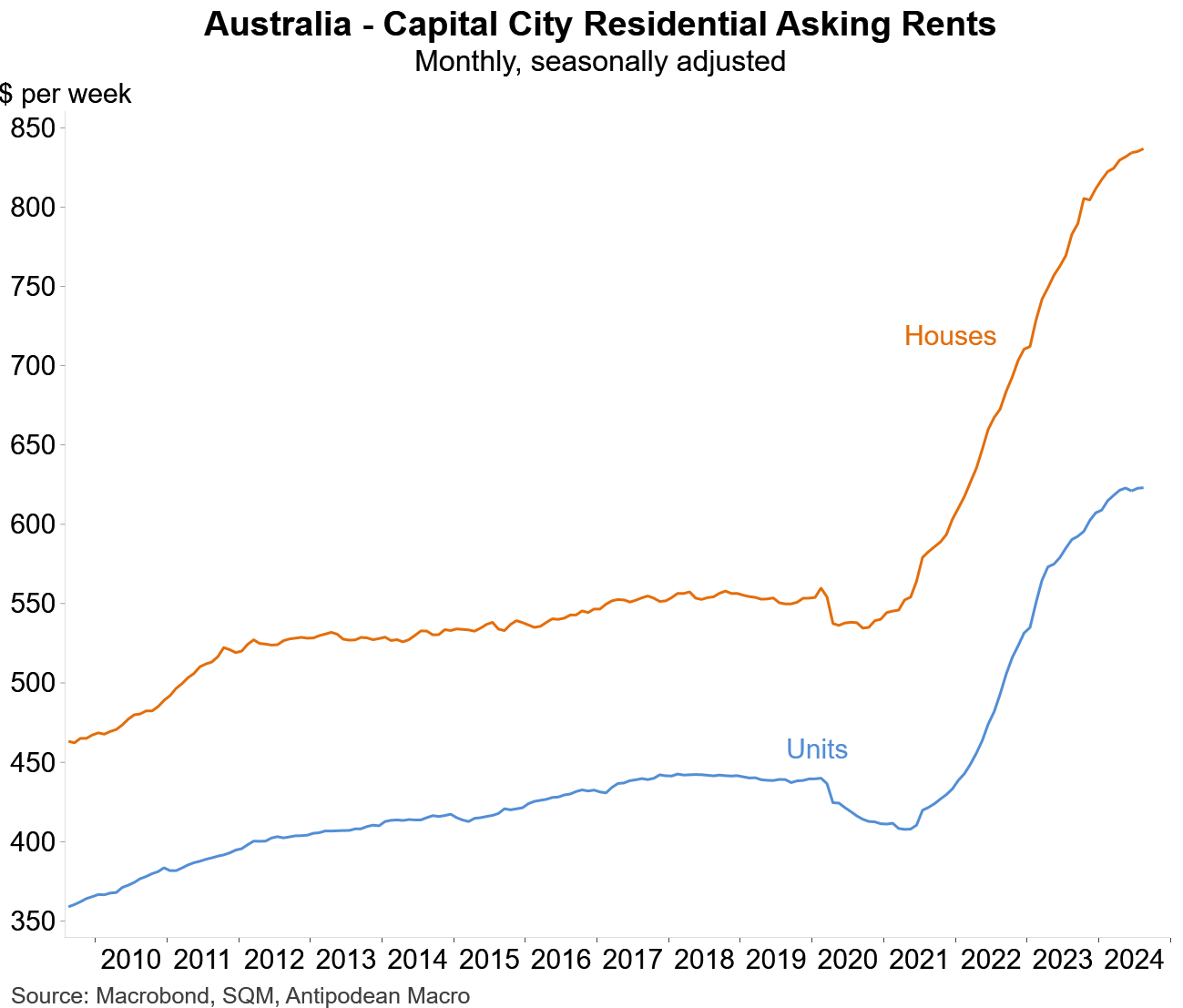

The enormous disparity between demand and supply pushed the nation’s rental vacancy rate to historic lows and asking rents to the moon.

Earlier this year, Finder’s Consumer Sentiment Tracker showed that 42% of renters were struggling to pay their rent, which was higher than the 37% of mortgage holders in the same position:

“Much of the conversation around rate rises focuses on homeowners, but it’s actually renters who are proportionally feeling the impact more, as they deal with flow-on rent increases”, Finder’s head of consumer research Graham Cooke said.

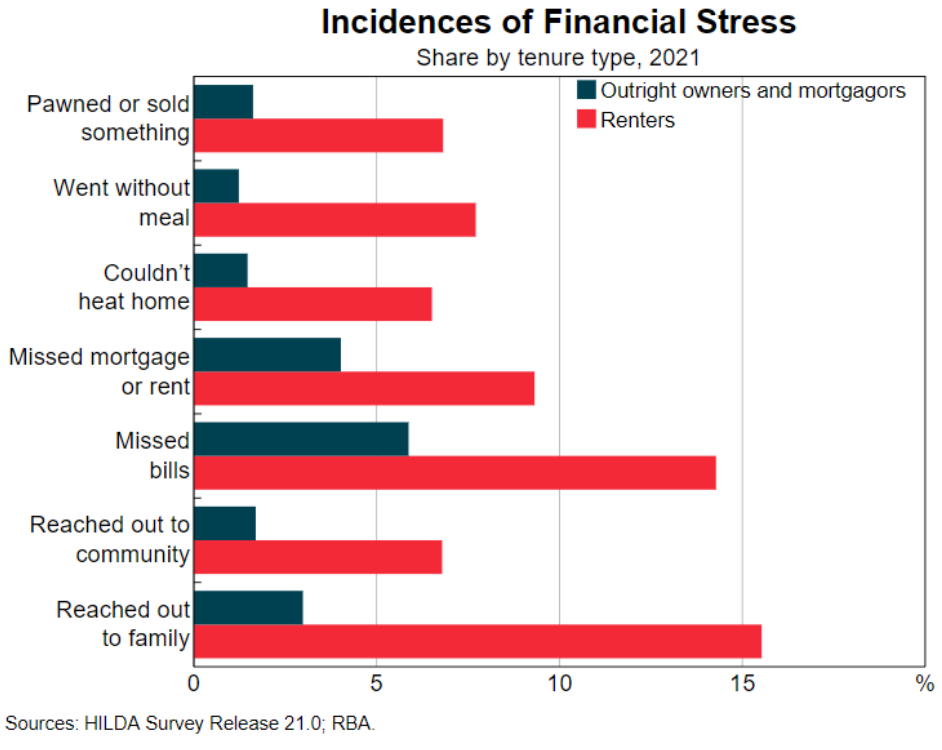

The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) corroborated Finder’s findings, noting that renters tended to experience financial stress more frequently than owner-occupier households:

This outcome reflected the fact that renting households tended to have lower wages and significantly smaller savings than mortgage-holding households.

Roy Morgan’s 2023 Wealth Report revealed that renters have fallen significantly behind homeowners.

According to this study, Australia’s wealth increased by 7.0% from March 2020 (prior to COVID) and March 2023.

This gain in wealth was mostly driven by a 43.2% increase in the value of owner-occupied housing, which rose from $4.16 trillion to $5.95 trillion.

Half of Australia’s population, predominantly homeowners, owned 95.4% of the country’s net wealth. The bottom half of the population, largely renters, saw its wealth share rise as well, although only from 3.6% to 4.6%.

Given this context, it was not surprising to read new data from the Australian Financial Security Authority (AFSA) showing that personal insolvencies are rising, with renters leading the way.

“Renters with unsecured debt, who have been slugged with above-inflation price hikes in the past few years amid supply constraints and surging population, make up more than nine in 10 personal insolvencies in Australia, despite making up just 21% of the population”, The Australian’s Matt Bell.

“Households are starting to dig into their savings. There’s still a reasonable savings bundle, but at a micro level, particularly with those who have less savings and at the more vulnerable end of society, they have no more savings and are hanging on by a thread”, ASFA chief executive Tim Beresford said.

“What’s keeping them afloat is employment. If we were to see unemployment go from a 4 to a 5 (per cent), you would start to see that number rise even faster than 14,800. It would go much higher than that”.

“We have an overwhelming number of people who are renters in our system, with quite frankly a relatively low level of debt. It gives you a sense that we are skewed to renters, to those who are more vulnerable, and we are skewed to those that have modest debt relative to the broader Australian context”, he said.

The above data is more evidence of why the federal government’s mass immigration policy is so destructive and increases inequality.

Record immigration has driven home values higher, despite high interest rates, which has worsened wealth inequality.

It has also pushed tenants to the edge financially by making them pay more for basic shelter.