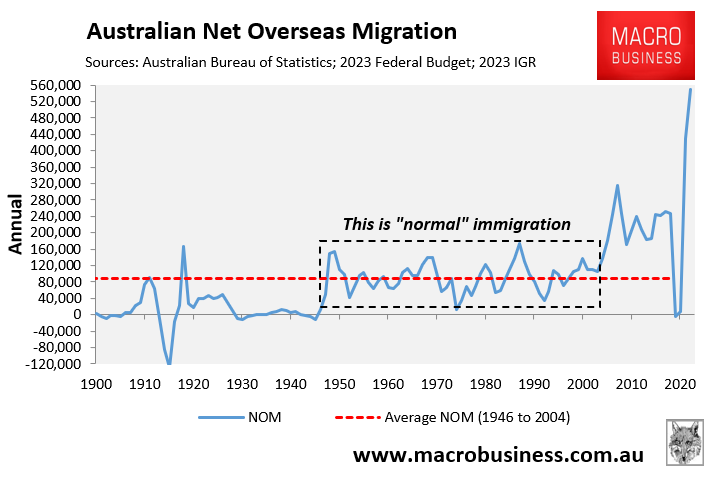

Australia’s population is booming courtesy of record net overseas migration:

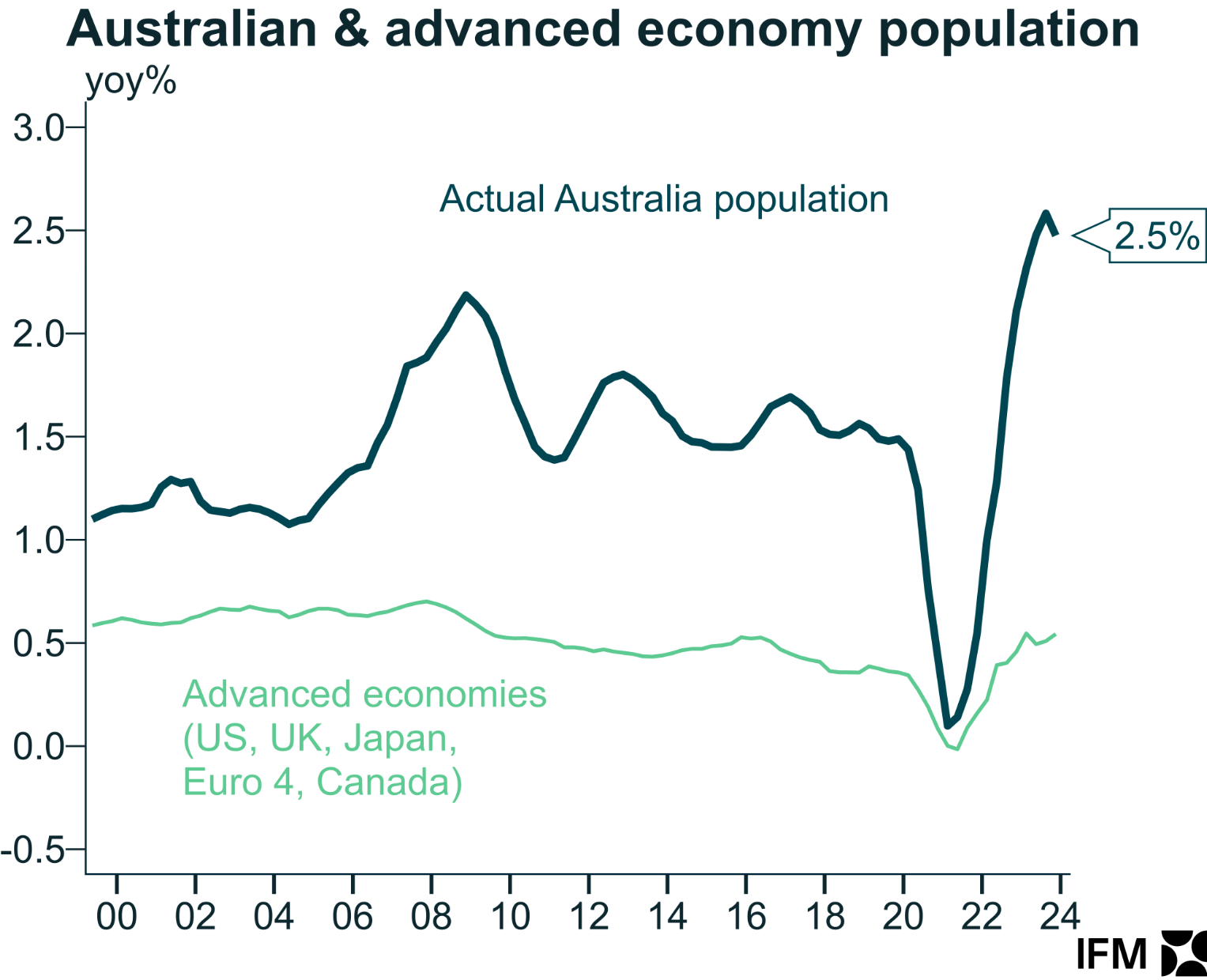

Australia’s population grew by 2.5% in 2023—the fastest rate since 1952—dwarfing the average growth of advanced nations:

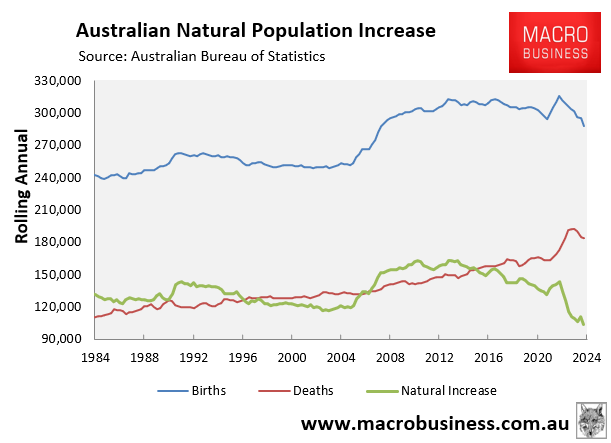

However, while Australia’s population has grown like a science experiment, fewer families are having children.

The following chart shows that there were 287,000 births in Australia in 2023, the lowest reading since the year to March 2007.

These 287,000 births were offset by 183,100 deaths, delivering a natural increase of only 103,900 people in 2023:

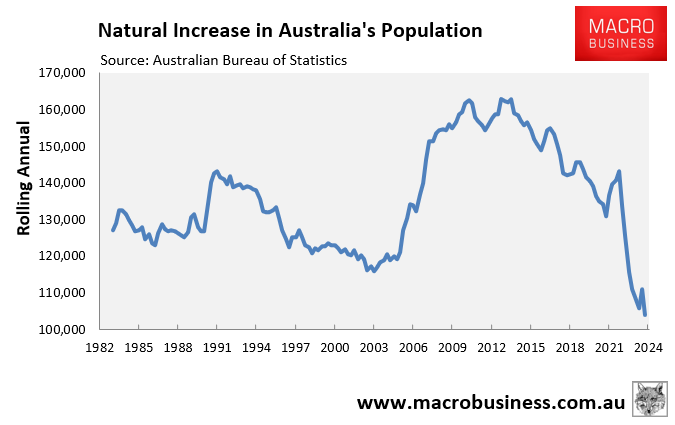

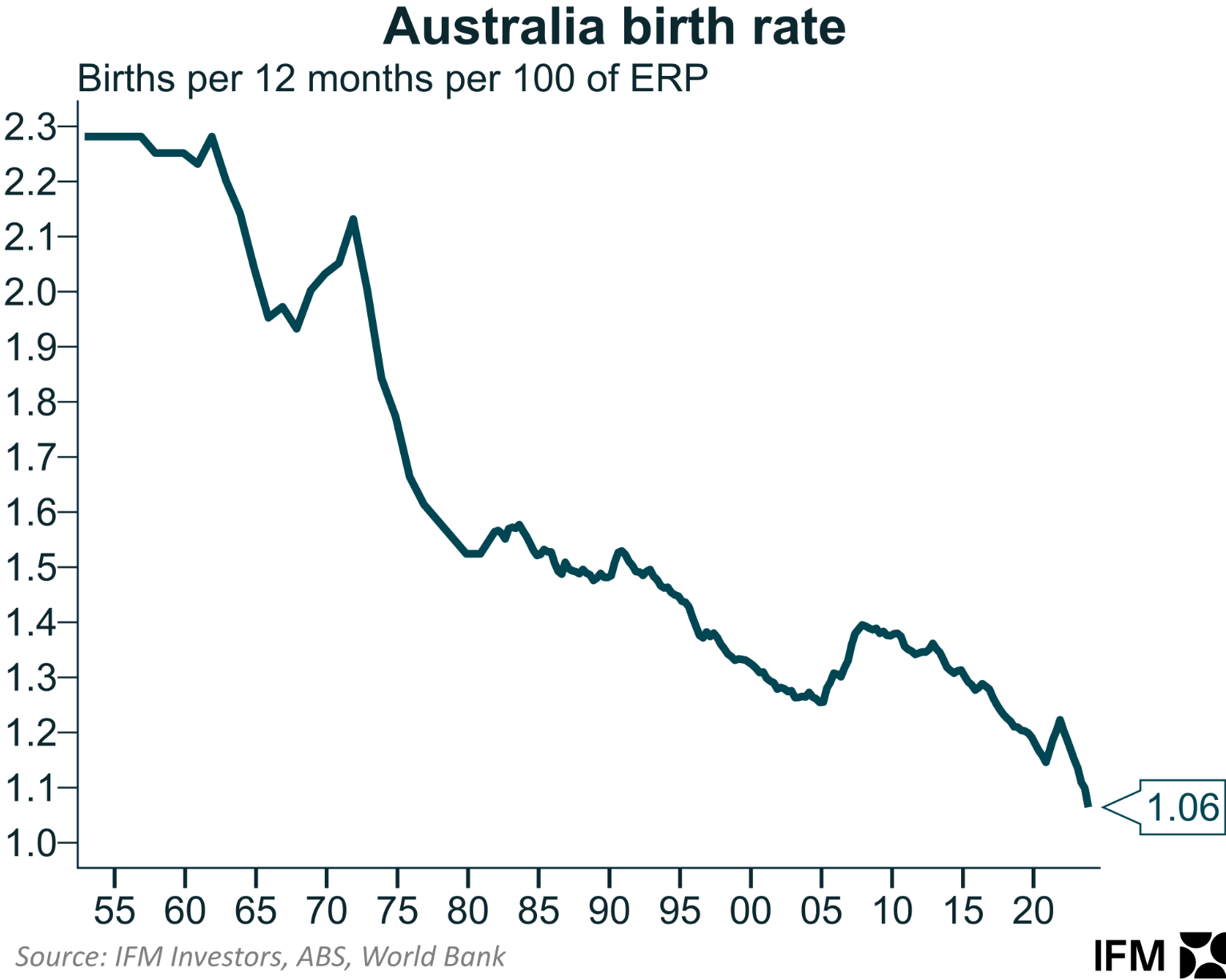

As a result, Australia’s birth rate fell a record low of just 1.06%, according to Alex Joiner at IFM Investors:

It is safe to say that high rates of immigration are having a limiting effect on local birth rates.

According to HSBC research published in January, “a 10% increase in house prices leads to a 1.3% drop in birth rates, and an even sharper fall among renters”.

Record immigration is a significant driver of Australia’s growing property prices and rents. Thereby, it is working against plans to start a family.

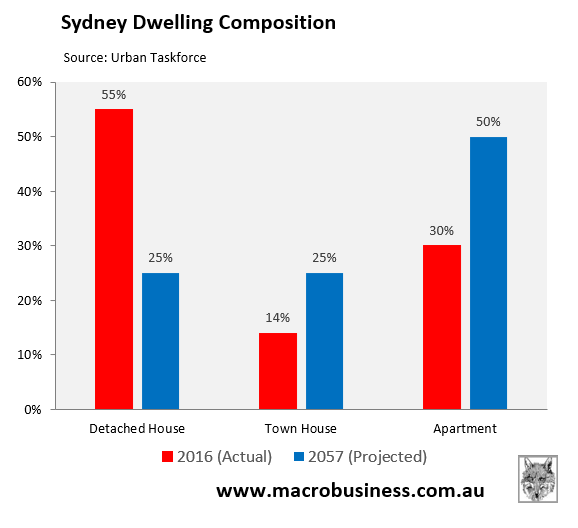

Extreme immigration-driven population expansion has also transformed (and will continue to change) the composition of the housing stock in our major capital cities, from family-friendly houses with backyards to family-unfriendly one and two-bedroom high-rise apartments.

SBS News covered this issue and noted that new apartment developments are incompatible with raising a family:

RMIT University urban planning expert Liam Davies said if Australia didn’t figure out how to provide more three and four-bedroom properties catering to families in inner and middle city areas, cities would become “very separated”.

Davies said developers rarely included three-bedroom units in high-rise apartments, focusing mainly on one or two bedrooms — aimed at investors — because they were more profitable…

“I think that’s a problem that we’ve got — family homes aren’t being built in apartments in inner and middle suburbs — they’re still standalone, separate housing in the outer suburbs and in the growth areas,” he said.

Davies said if family homes weren’t included in more central large housing developments, prices for the few suitable properties available in these areas would keep rising.

“Middle-income Australians won’t be able to raise families in family homes in the inner and middle suburbs. They’ll be increasingly forced further out,” Davies said…

Davies said no one was focusing on ensuring large developments cater to families.

“No one’s doing this,” he said.

Australia’s immigration and housing policies are discouraging families from having children.

In response, the federal government has compensated for the declining birth rate by increasing net overseas migration to unprecedented levels, making housing more cramped and expensive, as well as making jobs less secure for younger Australians of childbearing age.