The Q2 national accounts and the latest labour force data showed that the public sector is powering the Australian economy, masking the deep private sector recession.

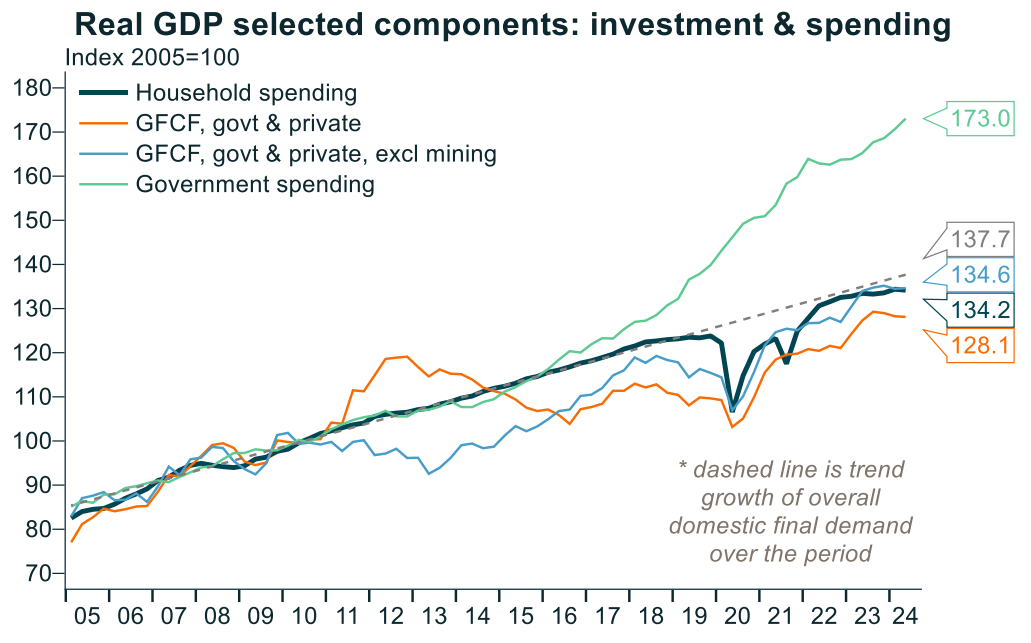

Source: Alex Joiner (IMF Investors)

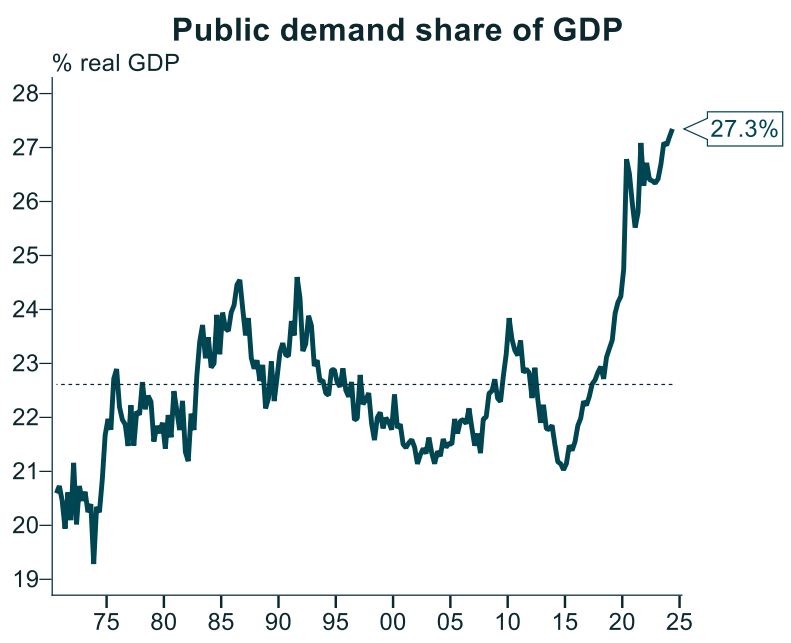

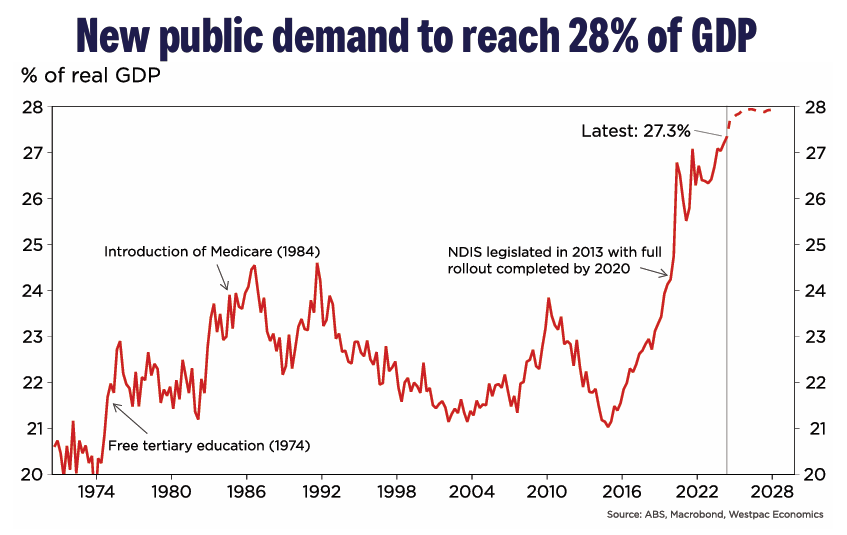

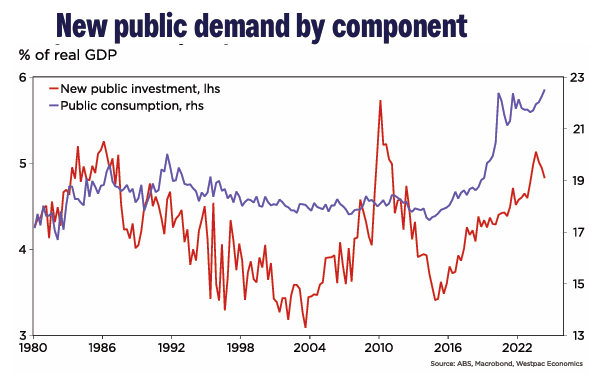

Government spending hit a record-high share of GDP in Q2 after growing by 1.5% over the quarter:

Source: Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

By contrast, the market sector declined by 0.6% over the quarter.

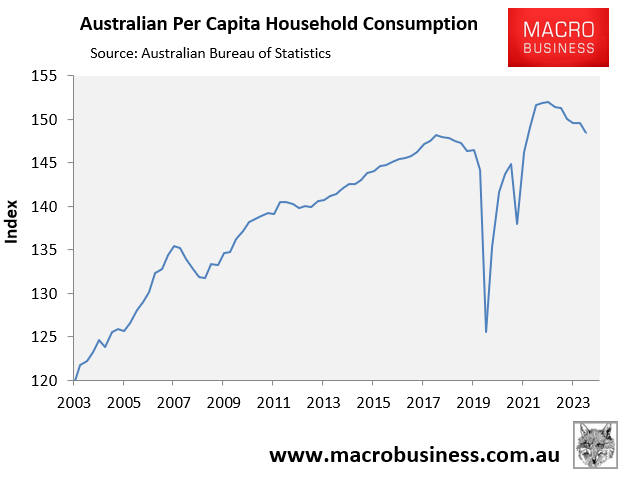

Australian households, in particular, are experiencing a deep recession.

The Q2 national accounts showed that household spending per capita had contracted for six straight quarters, down 2.4% over that period:

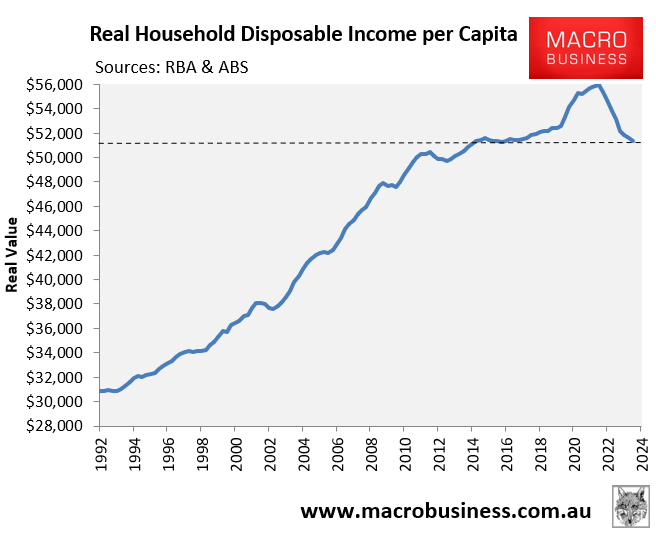

To add further insult to injury, real per capita household disposable income was tracking 8.2% below its Q2 2022 peak, according to the Q2 national accounts.

This represents one of the most significant declines in the world:

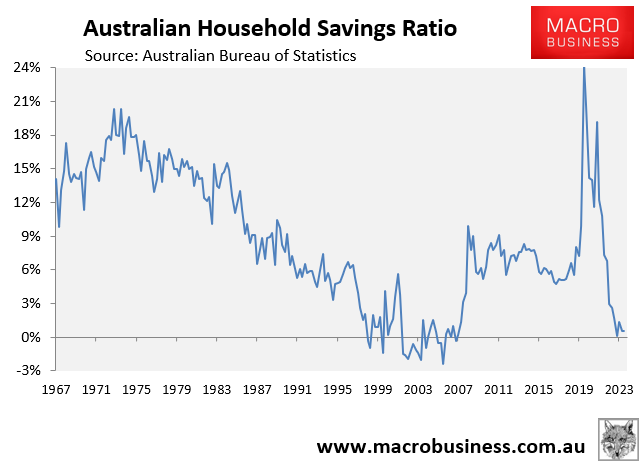

The decline in household consumption would have been even deeper if not for the collapse in the household savings rate to only 0.6%, which implies negative disposable savings when compulsory superannuation savings are taken into account:

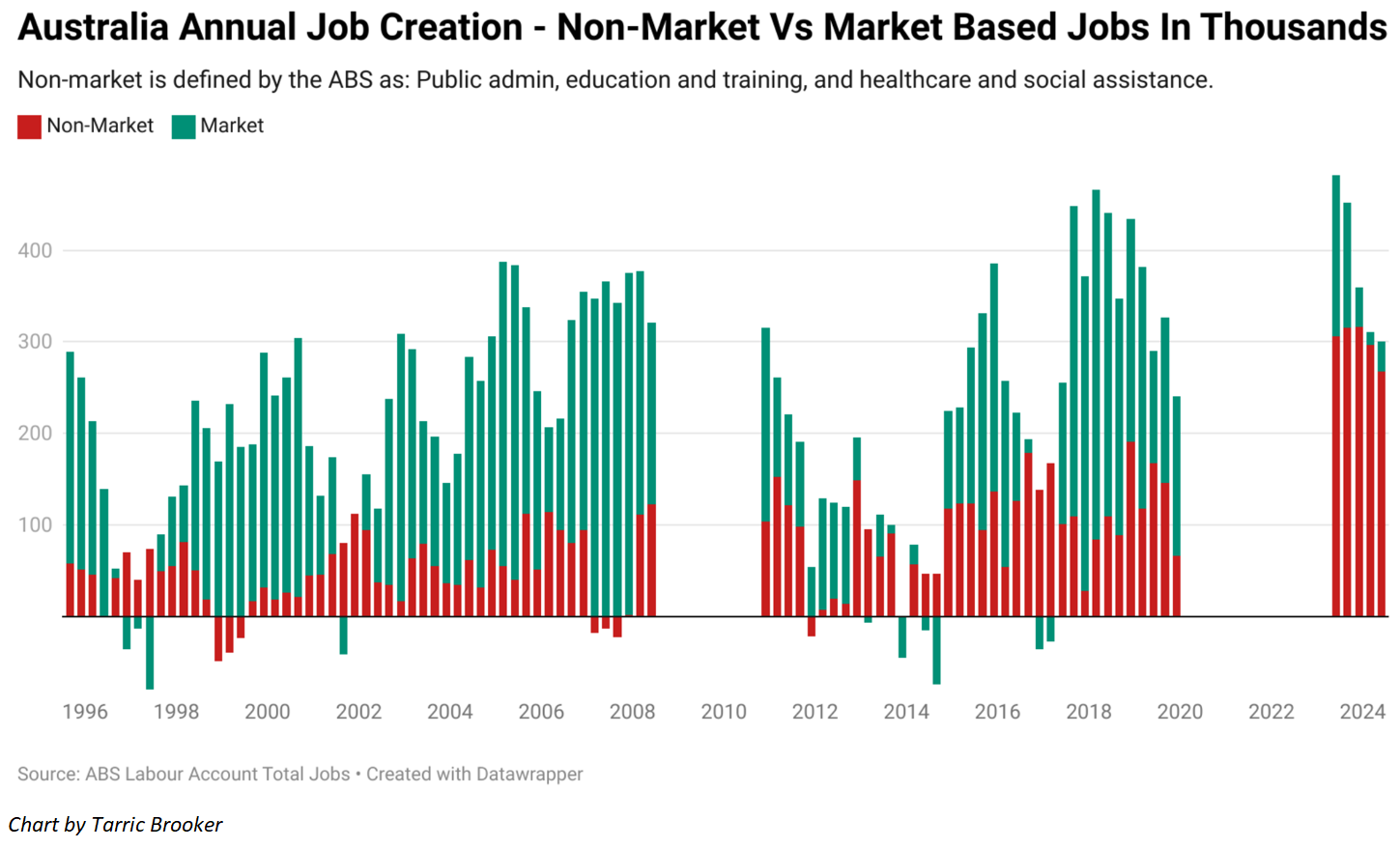

The situation is similar with Australia’s labour market, where the lion’s share of jobs are being created via government spending.

Q2 2024 Labour Market Account from the ABS showed that 268,000 jobs were created in government-funded roles in 2023-24, whereas only 33,000 new jobs were created in the market sector (i.e., in all other industries):

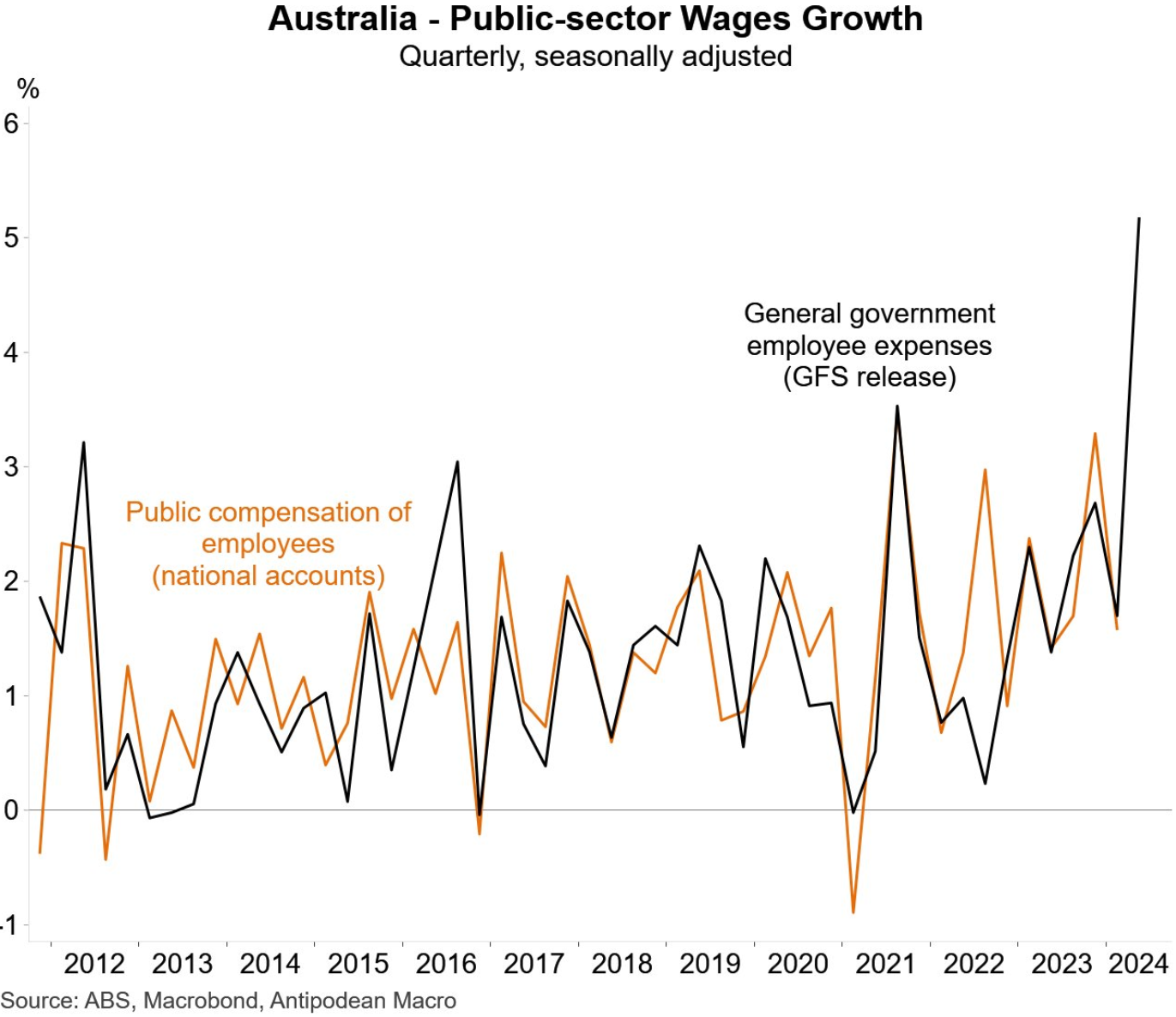

In a similar vein, total public sector wages surged by around 5% in Q2:

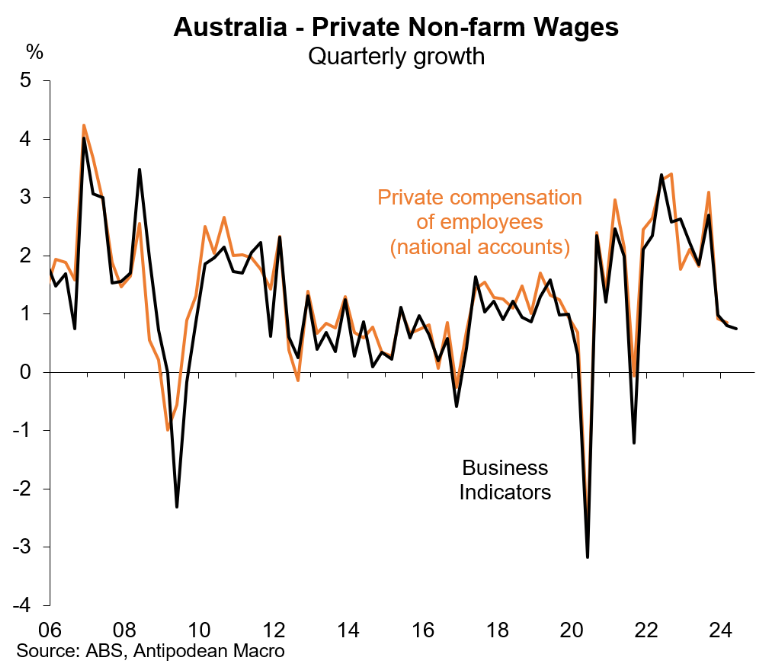

By contrast, non-farm private sector wages rose by just under 1% in Q2:

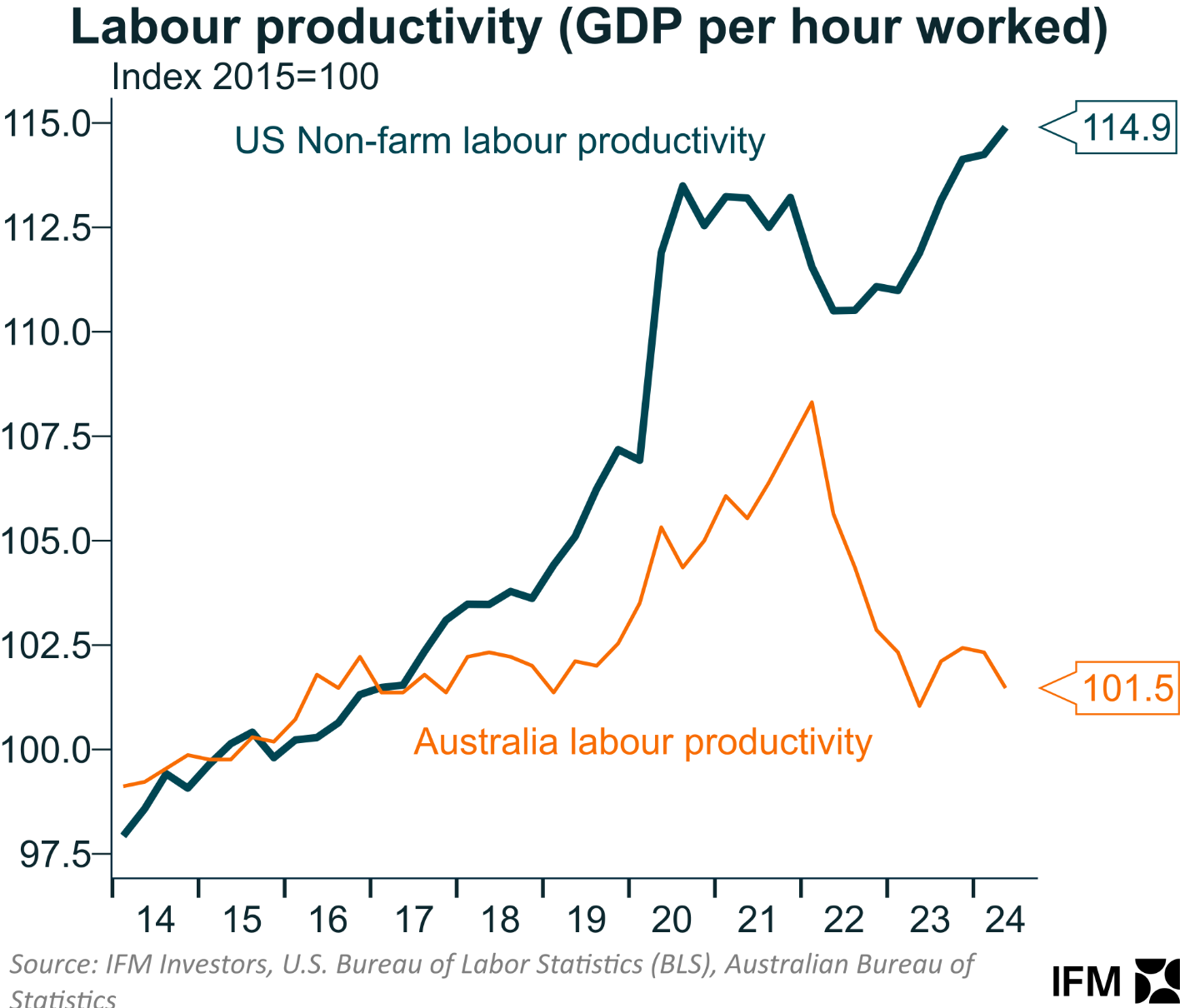

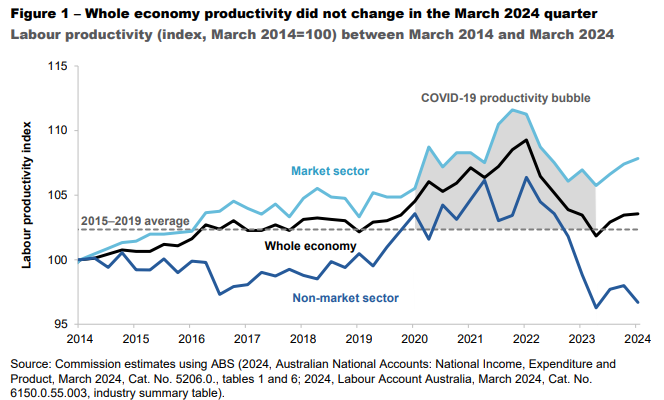

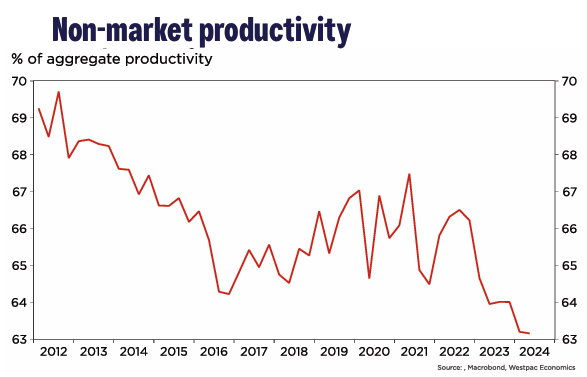

Australia’s labour productivity is deplorable, tracking at around 2016 levels:

Much of this productivity decline can be traced back to the explosion in government-funded jobs, which have historically experienced poor productivity growth:

With this background in mind, it is concerning to read Westpac’s forecast that government spending will continue to rise as a share of the economy.

“The increase in new public spending as a share of the real economy is unprecedented in speed and scale”, Westpac senior economist Pat Bustamante said.

Bustamante claimed the surge in government spending rivalled the mining boom in terms of its significance for the structure of the economy.

However, unlike the mining boom, current levels of public spending can only be funded by recurrent government revenue and higher taxes.

“The [spending] increase to date has been driven by government consumption, essentially the increased provision of subsidised public goods and services including childcare, education, healthcare, aged care and disability support”, Bustamante said.

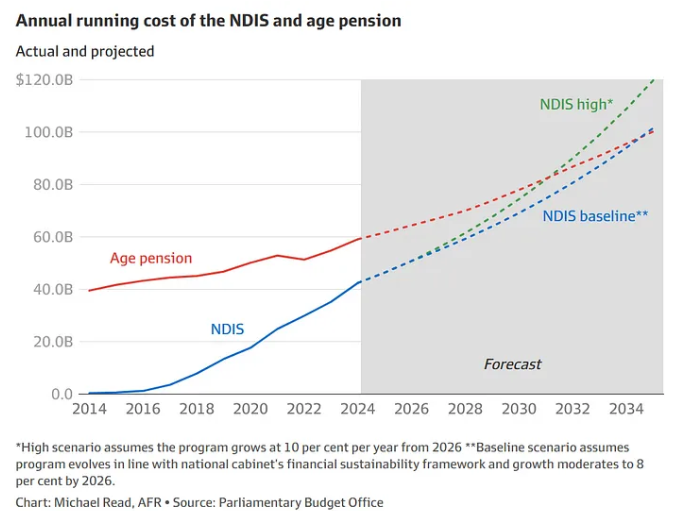

Much of the increase in public spending relates to the NDIS, which is growing in cost by around 20% a year and is projected to hit $100 billion in annual spending in around a decade.

The expansion in public spending necessarily means slower productivity growth, warns Bustamante.

Marcel Thieliant, head of Asia Pacific at Capital Economics, also warned that the explosion in government spending also hampered the Reserve Bank of Australia’s fight against inflation.

“With the economy still operating above capacity, that in turn will make it more difficult for the RBA to rein in persistently strong price pressures”, he said.

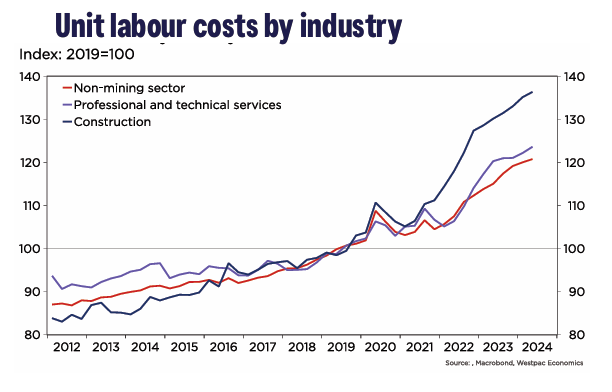

Bustamante agreed, noting that increased government spending in areas already short on resources, such as construction and healthcare, was siphoning resources from the private sector and driving aggregate demand.

“Increased spending in areas that are capacity constrained, such as infrastructure construction, is elongating the disinflationary process, adding to the RBA’s concerns”, Bustamante said.

In other words, record government spending means that interest rates will need to remain higher for longer, negatively impacting household disposable income.

Therefore, a softer landing for the economy from record government spending means a harder landing for Australian households.