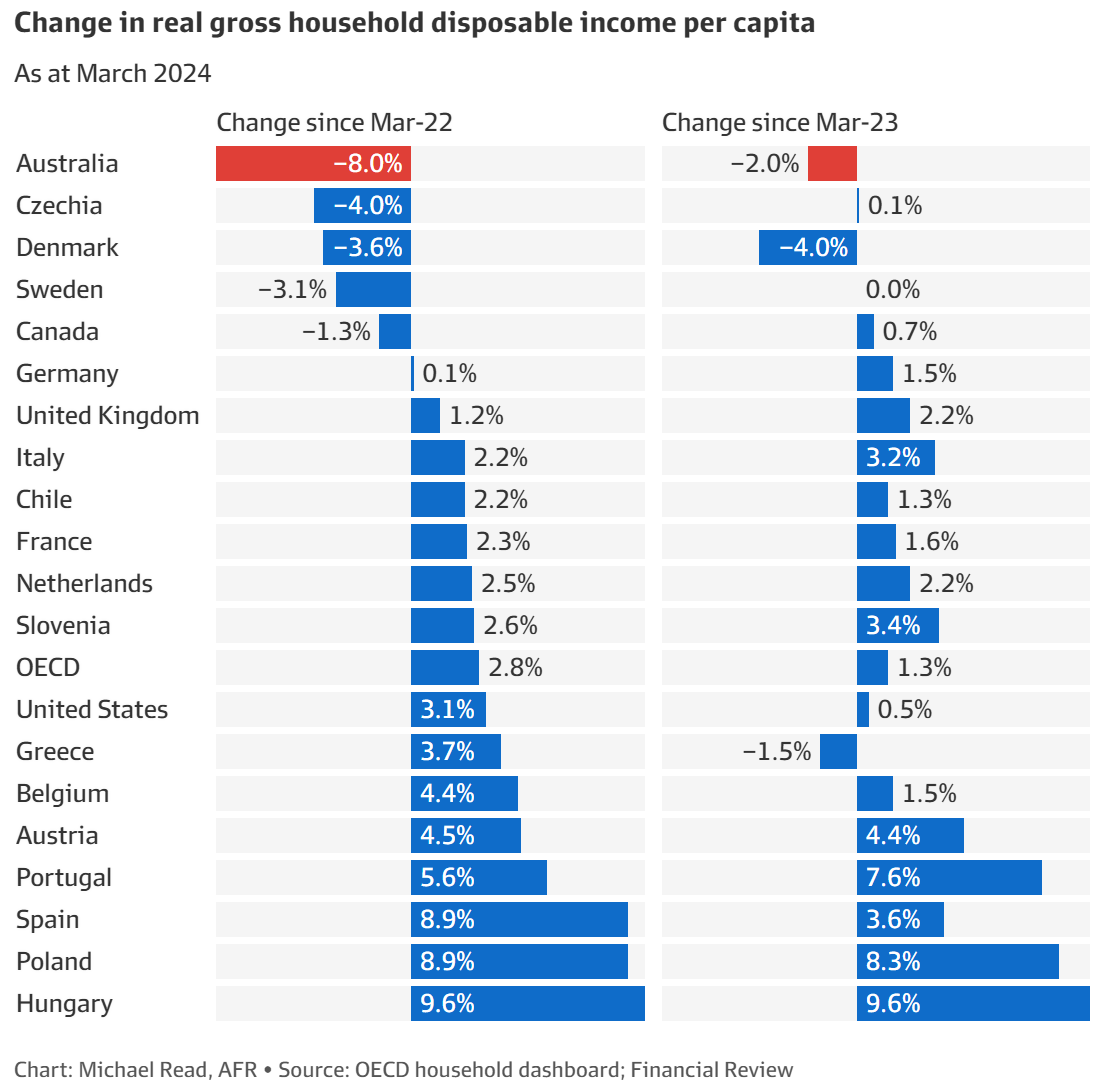

The AFR’s Economics Correspondent, Michael Read, published an analysis showing that “Australian households experienced the largest fall in disposable incomes across the OECD over the past two years”:

According to OECD data compiled by Read, real per capita household disposable income declined by 8.0% over the two years to March 2024. This compares to a 2.6% increase in disposable incomes across the OECD:

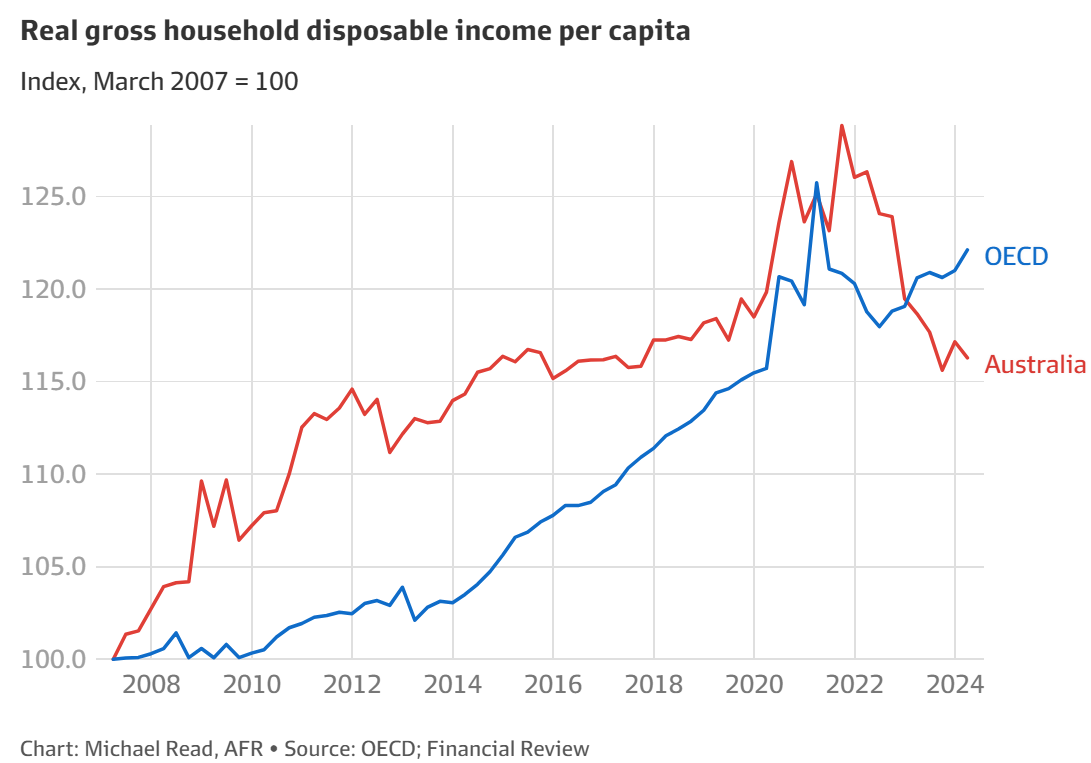

Moreover, Australia’s real per capita household disposable income in the March quarter of 2024 was tracking at the same level as the December quarter of 2014:

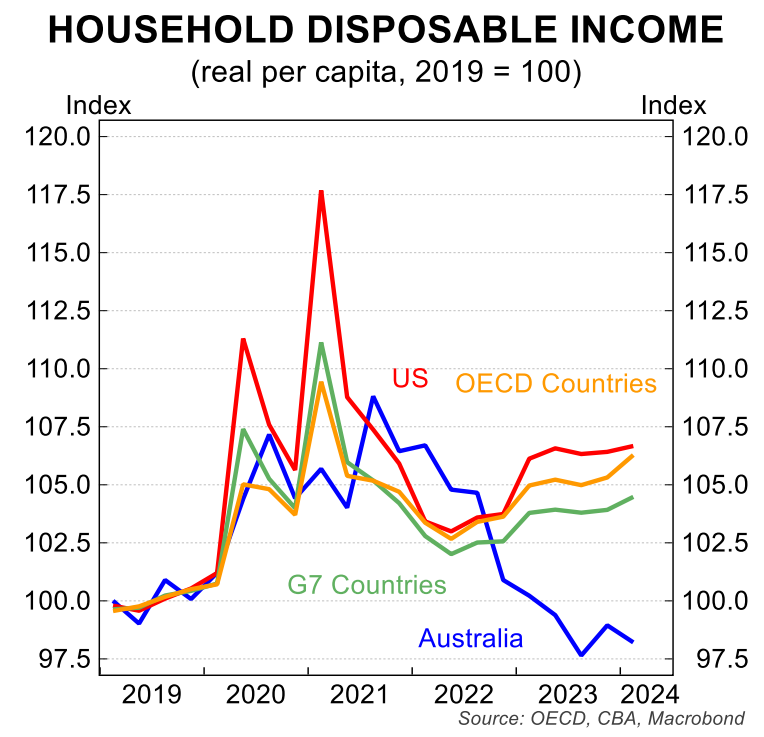

The following chart from CBA plots Australia’s real per capita household disposable income against a selection of major advanced nations:

As you can see, Australia is unique in that it has experienced a decline in household disposable incomes since the beginning of the pandemic, whereas the major advanced nations have recorded increases.

There are three main reasons why Australian households have suffered.

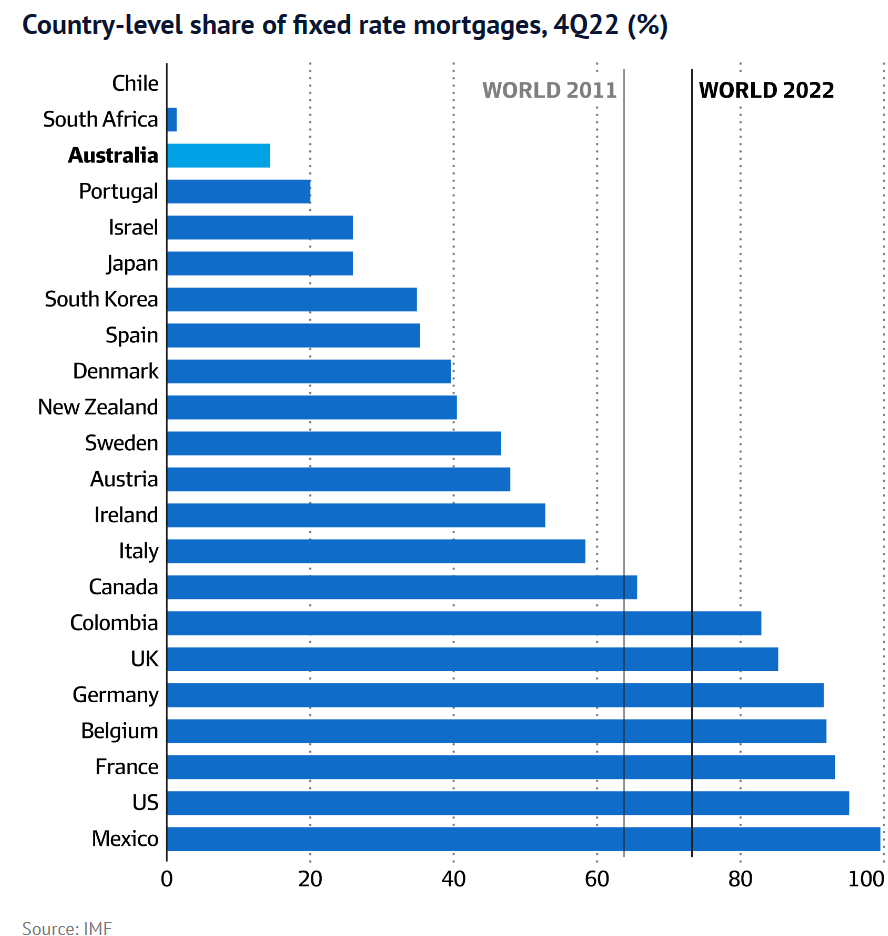

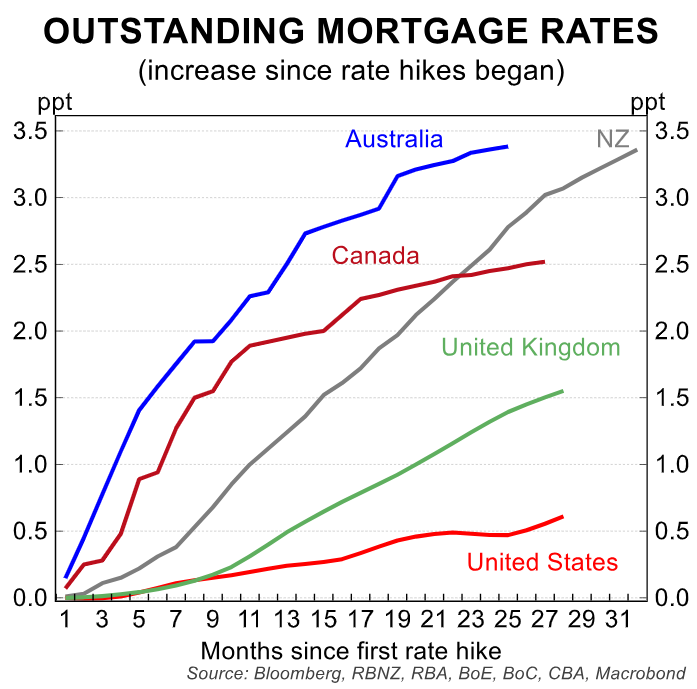

First, Australia is unique in that the overwhelming majority of mortgages in Australia are variable, whereas in most other nation’s fixed rate mortgages dominate.

This has meant that Australian mortgage holders have been hit especially hard by the rise in official interest rates:

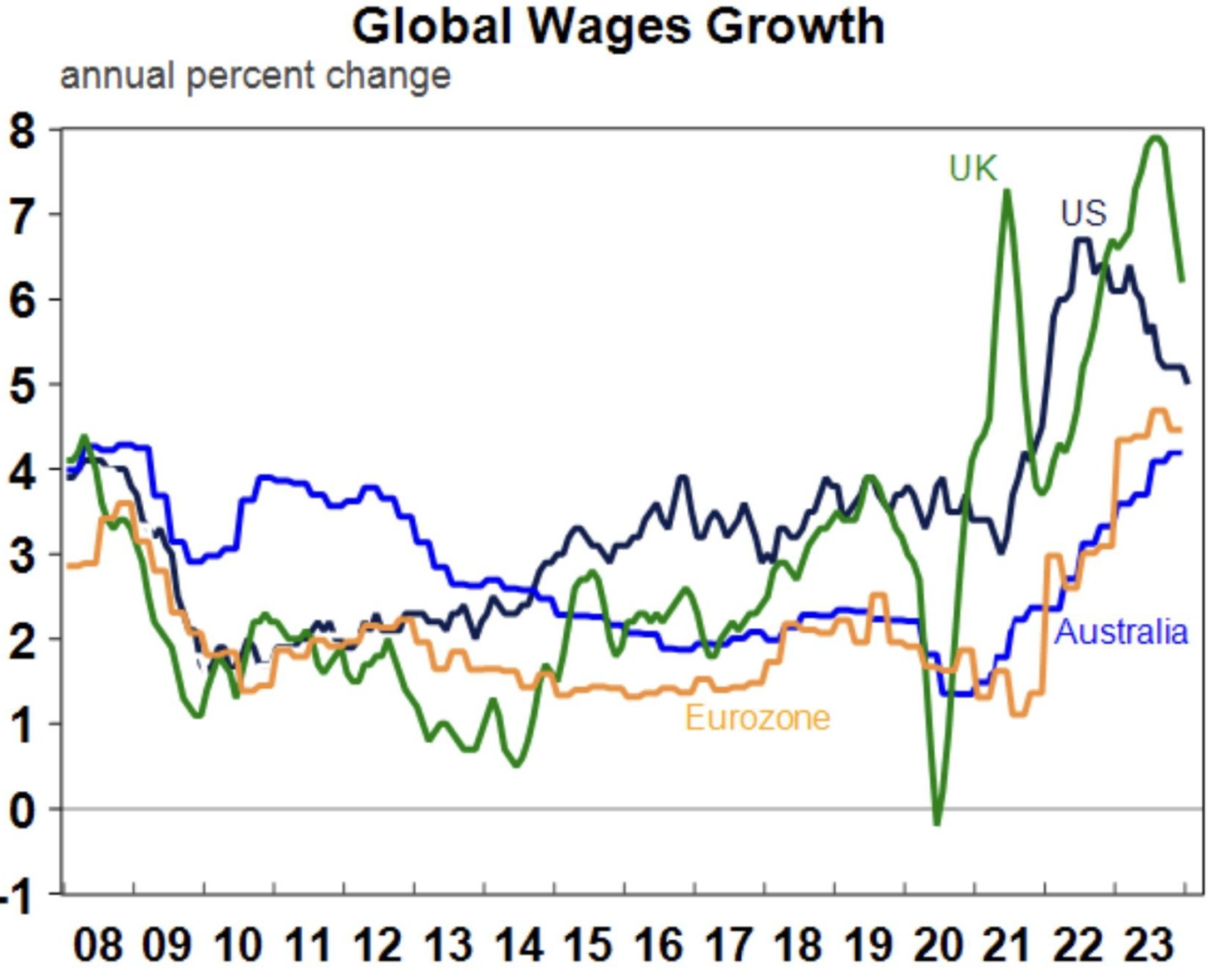

Second, Australians have experienced smaller wage growth than other advanced nations:

Source: AMP

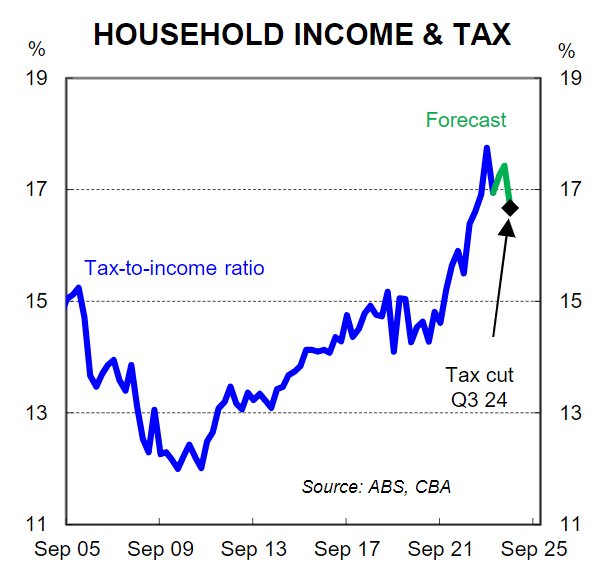

Third, Australians have experienced one of the sharpest increases in personal income taxes:

Australia is one of 21 OECD countries whose tax brackets are not inflation-indexed. Seventeen OECD countries automatically adjust their brackets to account for rising prices.

The expiry of the lower-middle income tax offset has also increased the personal income tax burden in Australia.

As a result, a near-record 16.4% of Australian household income was lost to personal income tax in the March quarter of 2024, according to the ABS national accounts.

HSBC economist Paul Bloxham noted that “exceptionally strong” population growth is the only thing keeping the economy afloat.

“The key here is that population growth has been exceptionally strong”, Bloxham said.

“So despite individual households being hit hard by higher interest rates and income taxes, there have been lots more new households that have arrived, which has meant the overall economy has kept growing nonetheless – albeit only slowly”.

In other words, extreme immigration is masking a ‘lost decade’ of declining living standards for Australian households.