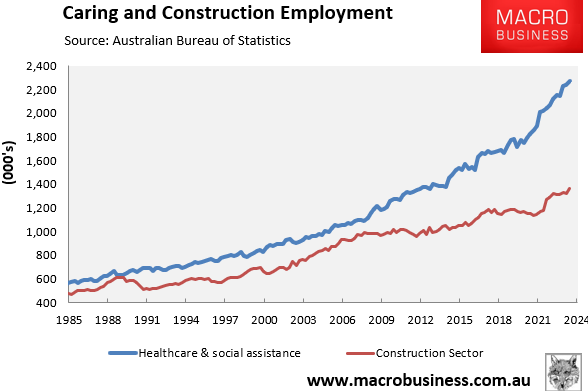

Analysis of data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) shows that the number of employees in the construction industry rose by just 2,772 to 1.22 million in the two years to June.

In contrast, the number of workers in the so-called ‘care economy’, which includes social assistance and healthcare services, has ballooned by more than 336,000 to 2.37 million over the same period.

Economist Saul Eslake claims jobs in the care economy have risen due to increased federal and state government spending on social services.

He added that the low growth in construction sector jobs reflects that the surge in immigrants under Labor has not included many skilled tradespeople.

“Although borders have been reopened since March 2022 and there’s been a surge in overall immigration numbers since then, there hasn’t been much by way of immigration of skilled construction tradespeople in that surge”, Eslake said.

“Notwithstanding strong demand for people with skills in construction trades, they simply haven’t been available”.

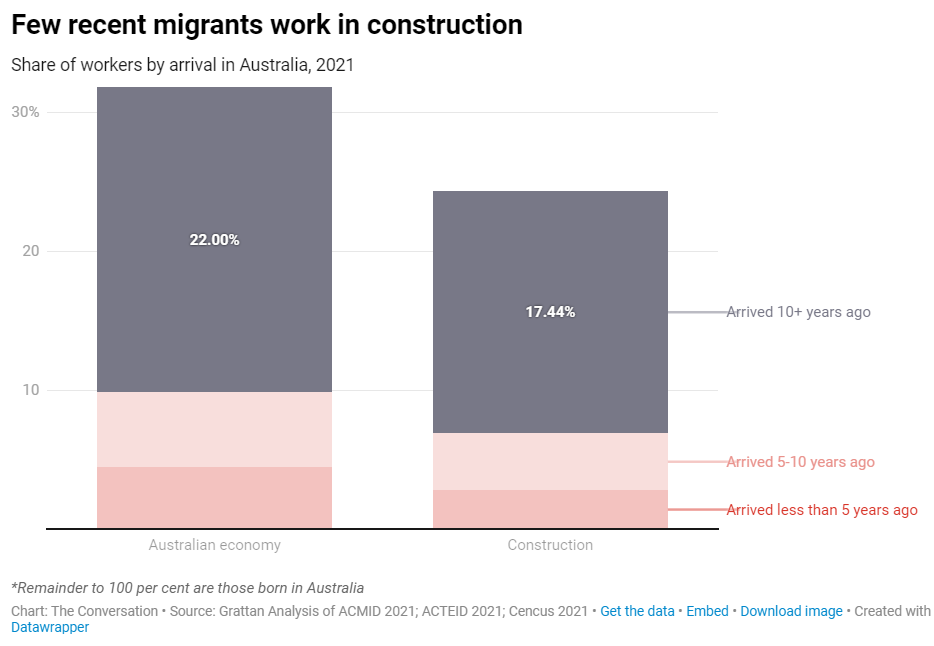

Saul Eslake has a point. Record immigration into Australia has dramatically lifted demand for housing, pushing up rents and prices.

However, migrants are woefully underrepresented in the construction sector, as illustrated below:

This means Australia’s immigration system directly drives up housing demand without sufficiently adding supply.

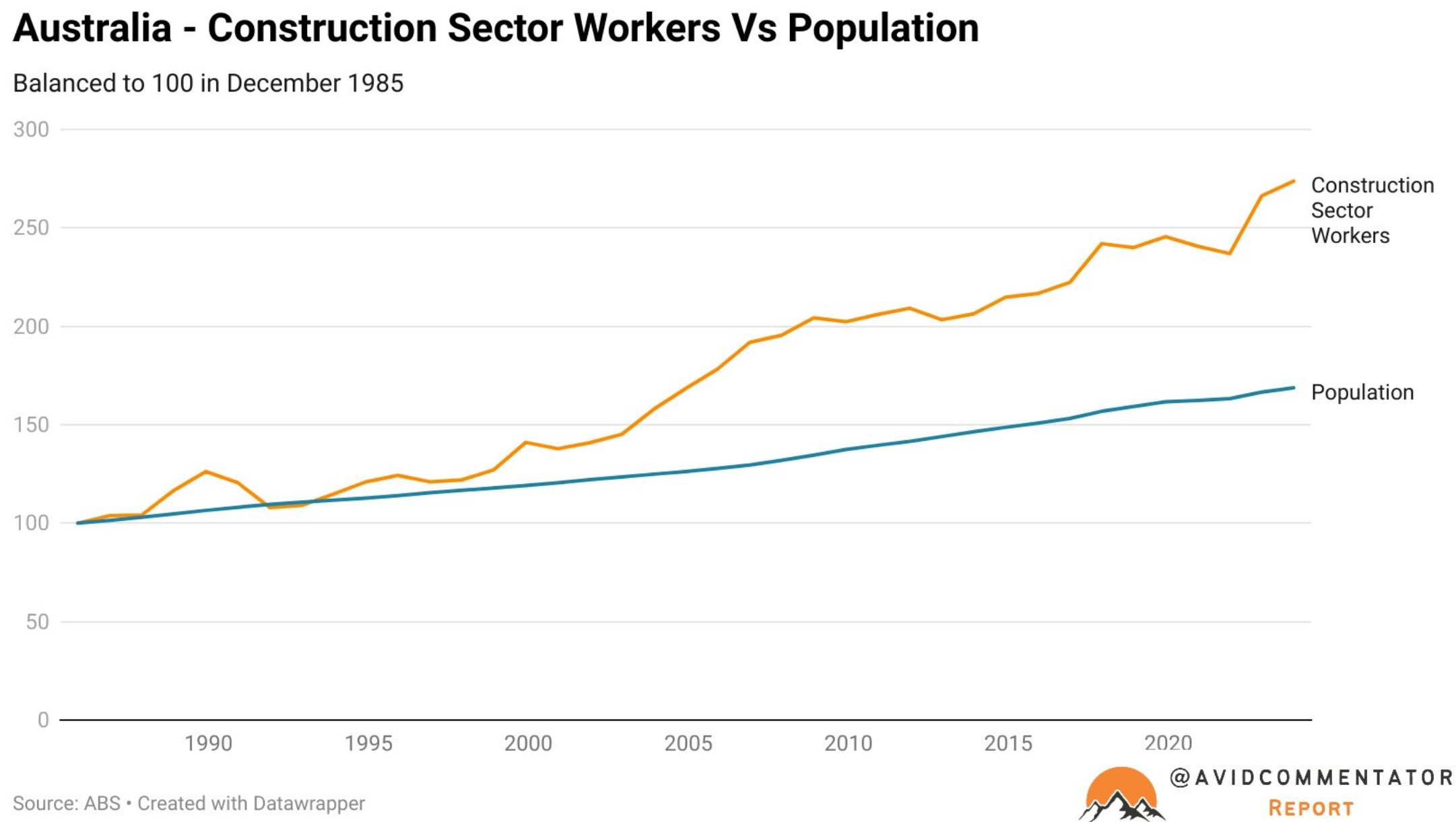

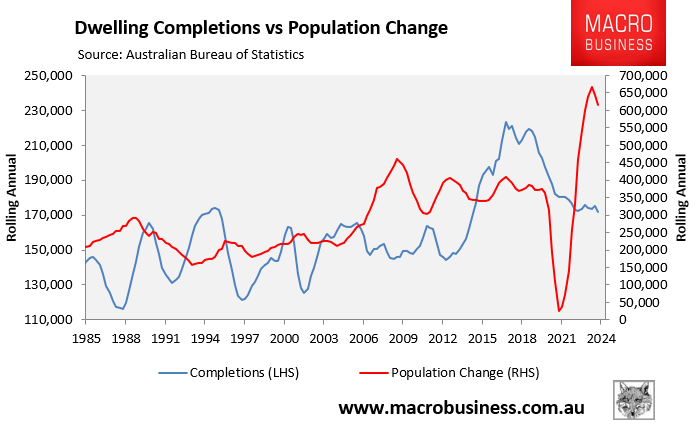

That being said, the following chart from Tarric Brooker shows that the number of construction workers in the Australian economy has outpaced the growth in Australia’s population:

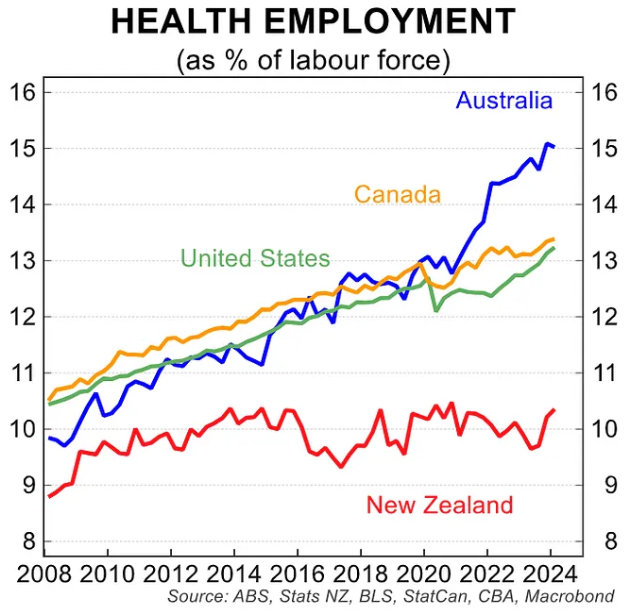

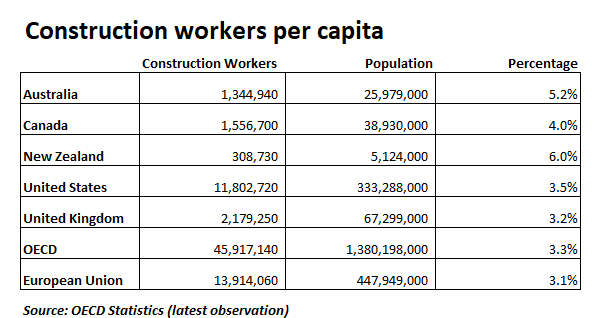

Australia also has one of the highest concentrations of construction workforces in the world relative to the population:

This data suggests that Australia should be adequately supplied with construction workers.

So why, then, has Australia’s dwelling construction lagged so badly behind population growth?

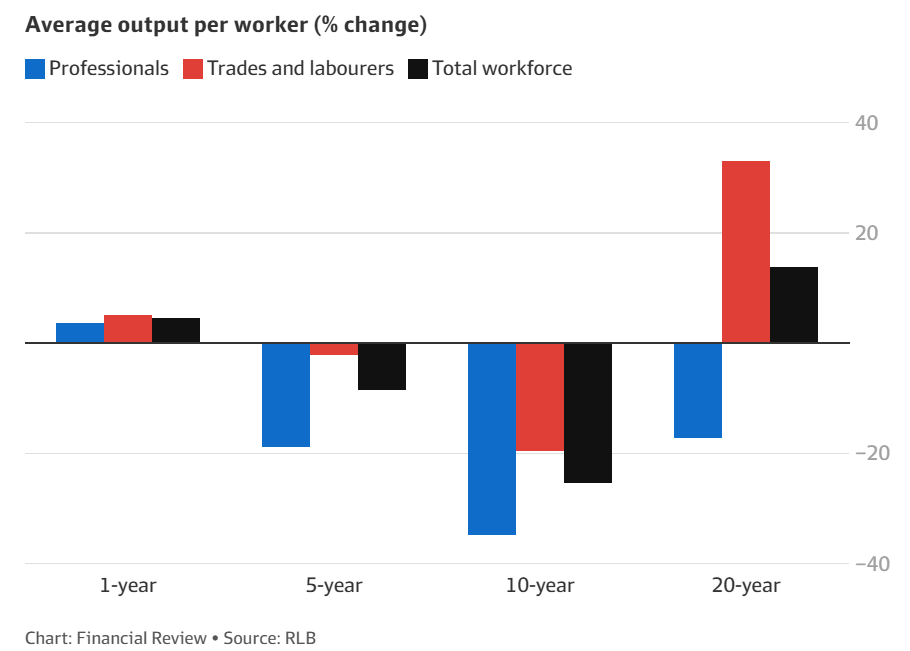

Australia’s construction sector appears to have been inundated with administrators in suits rather than tradespeople, which has bloated the workforce and contributed to lower productivity.

“The rapid rise in the number of professional workers that are now required to deliver projects across the country is at odds with the number of workers ‘on the tools’”, noted RLB’s Oceania director of research, Domenic Schiafone.

“In 2003, professional workers accounted for 28% of the construction workforce. By 2023, this had risen to 38%.”

Michael Bleby at The AFR noted that “the industry as a whole is suffering from an imbalance of too few workers on the ground and too many in the office”.

As a result, the construction sector’s productivity has deteriorated over the past decade:

“The growth in professional employees – professionals with tertiary degrees and building technicians with advanced diplomas – surged, rising 125% over the two decades from 242,900 to 547,300”, Bleby wrote.

“But the annual output per professional worker fell 17.2% to $470,900 from $568,900”.

Much like the rest of the economy, the construction sector has too many administrators and not enough front-line staff to produce and deliver the product.

The above analysis also highlights why Australia needs a much smaller immigration intake targeted at areas with genuine skills shortages.

Otherwise, Australia will continue to suffer chronic shortages of housing, infrastructure and services.