The RBA says the jobs market is too tight:

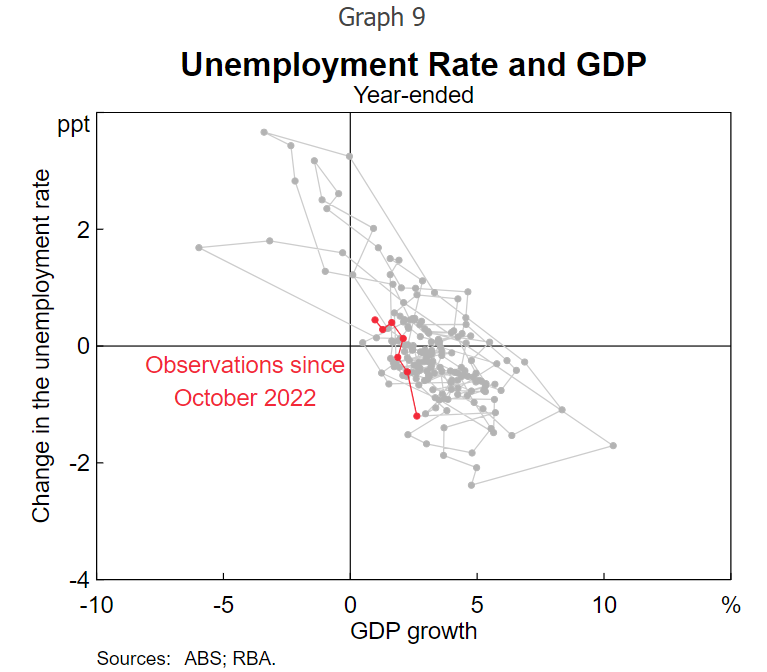

It’s true that recent unemployment rate outcomes have not been unusual given the historical relationship between changes in the unemployment rate and GDP growth rates (Graph 9).

What has been more surprising is the strength in the labour force participation rate and, as discussed earlier, the limited easing more recently in some measures such as the underemployment rate and average hours worked. This is occurring against a backdrop of slow momentum in the economy, a decline in vacancies and a gradually rising unemployment rate.

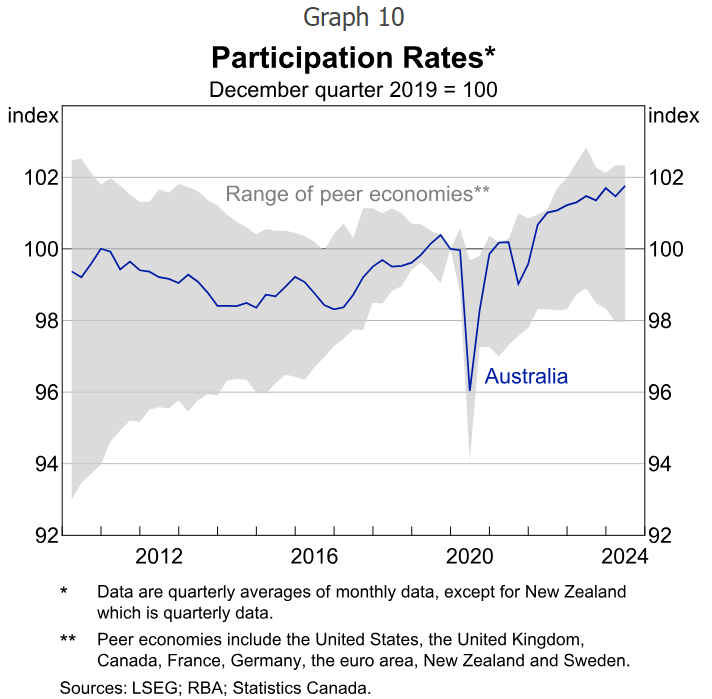

The participation rate has continued to trend upwards, reaching a record high in July. This has not been the experience in most other peer economies (Graph 10). Whereas participation rates amongst this group have largely begun to stabilise, in Australia the participation rate has continued to increase steadily in the post-pandemic period.

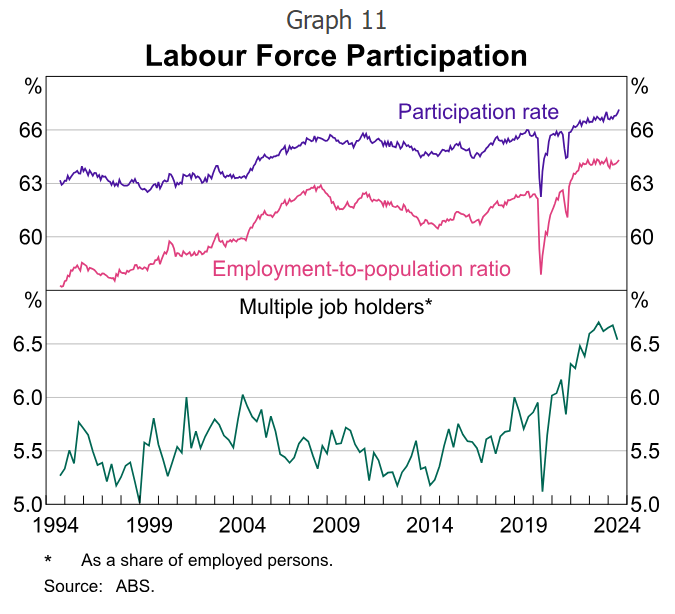

While the slowing in the economy may have weighed on the participation rate (all other things equal), other factors have likely provided support, including the longer-run trend towards greater female participation. We have also seen the share of employed people with multiple jobs continue to trend upwards since the pandemic, notwithstanding the decline in the latest quarterly data (Graph 11).

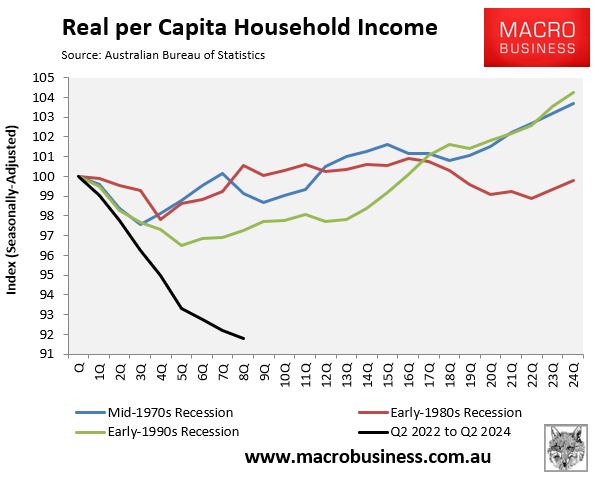

That does not seem such a mystery to me. In the circumstances of the Chalmers’ stagflation, rising participation is a logical outcome.

Everything is full, everything is expensive, and everybody needs more work to not go backwards.

Multiple jobs and more hours are the price labour pays to sustain living standards, which is, of course, a form of declining living standards.

If so, it raises the possibility that the RBA is misreading the function of high participation.

It is not a figment of labour market strength but of income weakness as wages comprehensively fail to keep pace with inflation:

If so, high participation does not represent wage pressures or inflation.

Just the opposite!