We know that Australia’s economy is being increasingly driven by government spending.

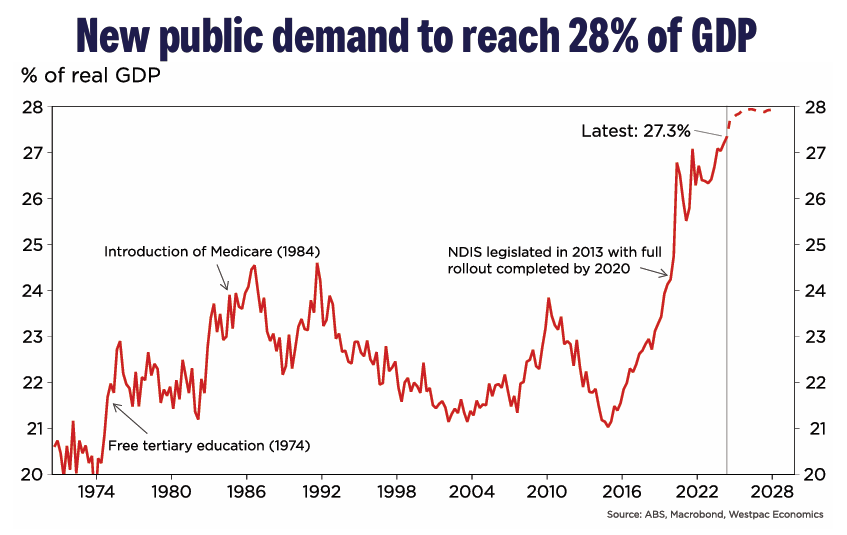

Public demand as a share of GDP hit a record high 27.3% in the June quarter of 2024, and Westpac forecasts that its share of the economy will continue to grow:

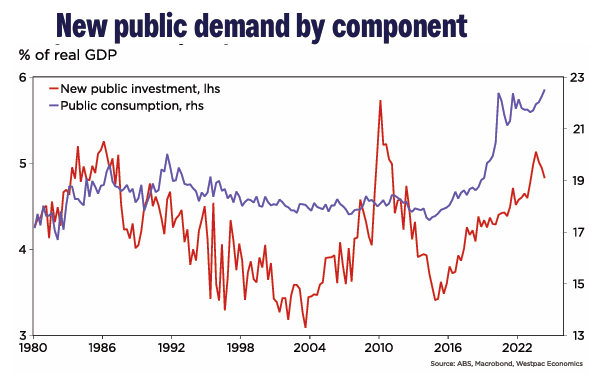

Much of this spending relates to the NDIS, which is growing in cost by around 20% annually and is projected by the Parliamentary Budget Office to cost around $100 billion annually in a decade:

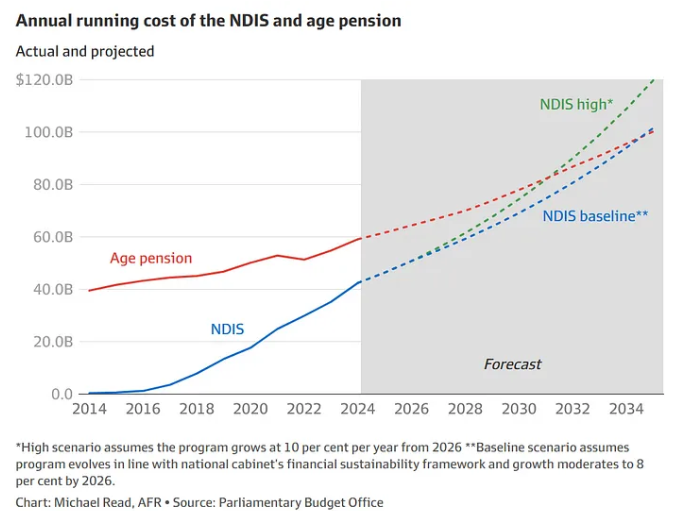

The government’s influence on the job market has been even more pronounced.

The Q2 2024 Labour Market Account from the ABS revealed that 268,000 jobs were created in government-funded roles in 2023-24, whereas only 33,000 jobs were created in the market sector (i.e., all other industries):

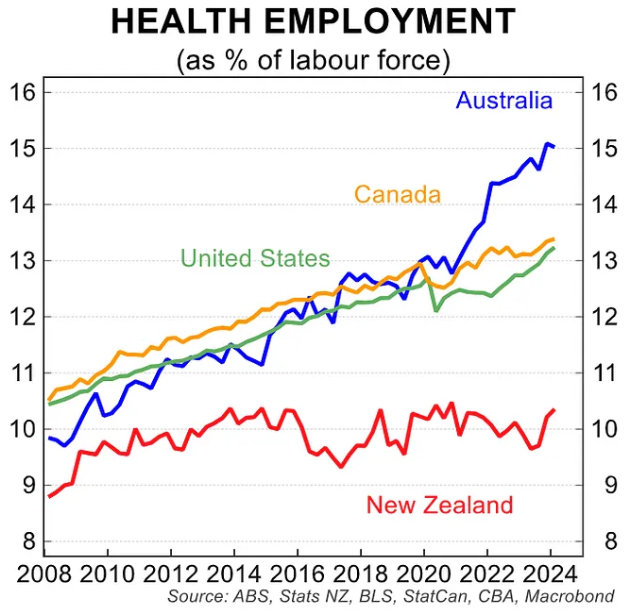

The following chart from CBA shows that the growth in healthcare & social assistance jobs in Australia has dwarfed other Anglosphere nations since 2021, reflecting the expansion of the NDIS:

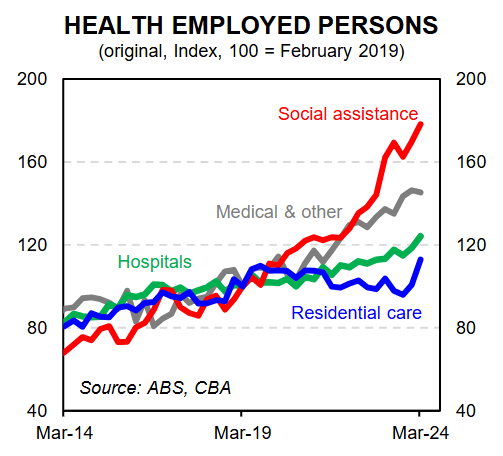

Most of these new roles have been caring jobs in the social assistance category:

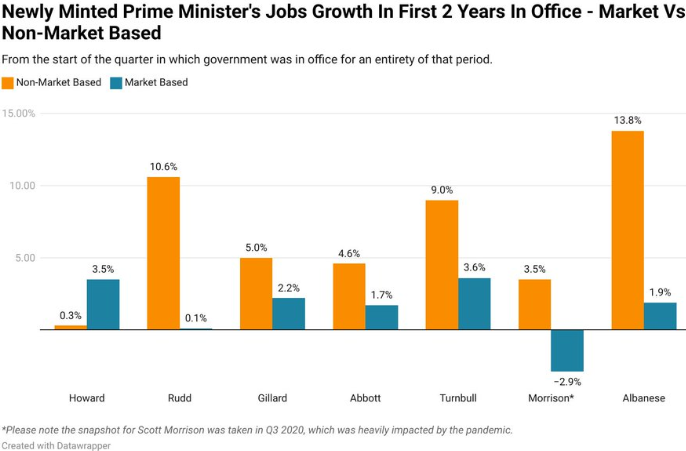

Independent economist Tarric Brooker has created the following chart tracking job growth across the first two years of the past seven Prime Ministers:

According to Brooker, “Albo wins the crown for the highest level of non-market based jobs growth of any PM since records began”.

The number of government-funded (non-market) jobs ballooned by 13.8% in the first two years of the Albanese government, easily eclipsing the 10.6% growth recorded under the Rudd government and 9.0% recorded under the Turnbull government.

By contrast, the 1.9% growth in market-based jobs under the Albanese government ranks fairly poorly.

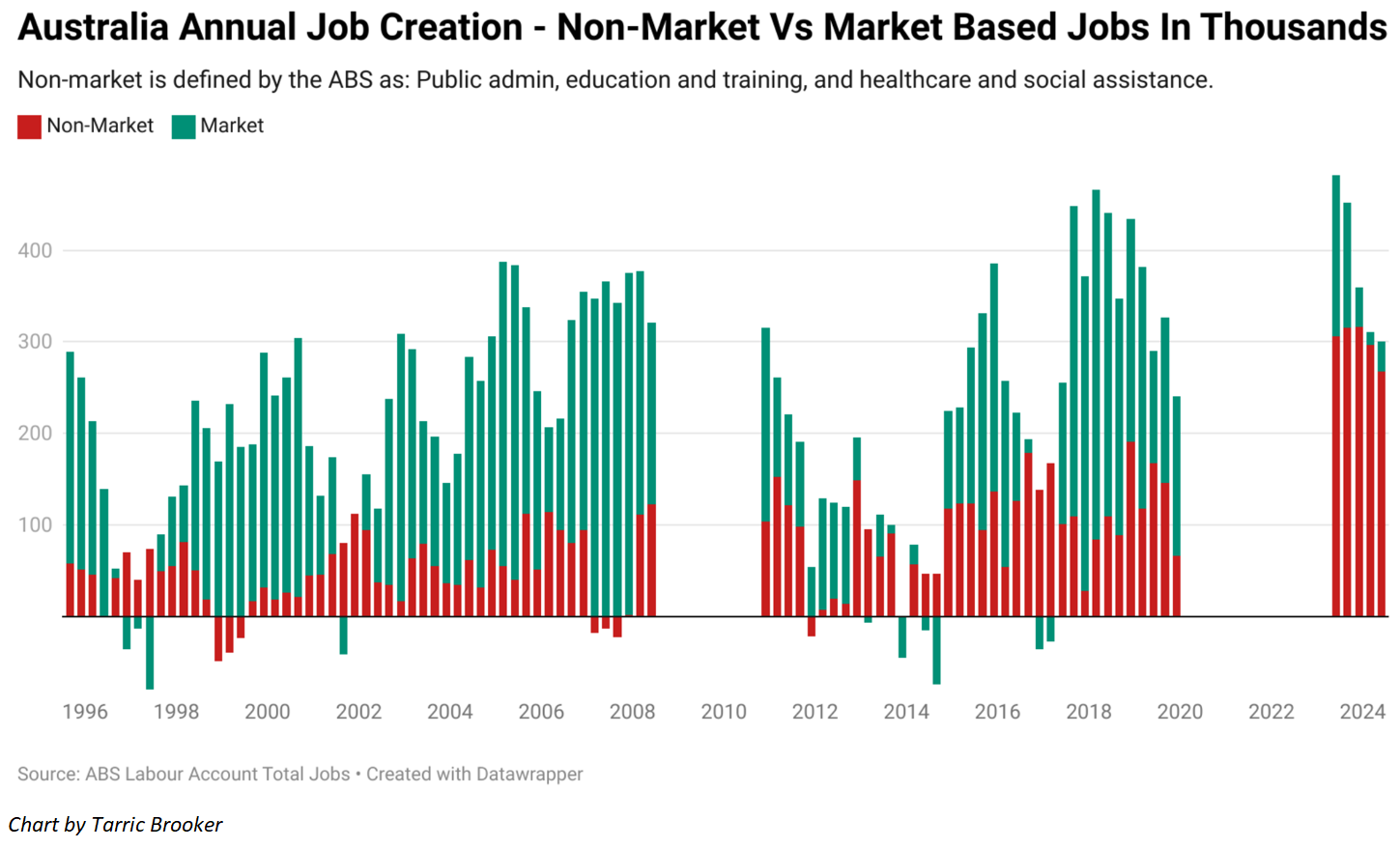

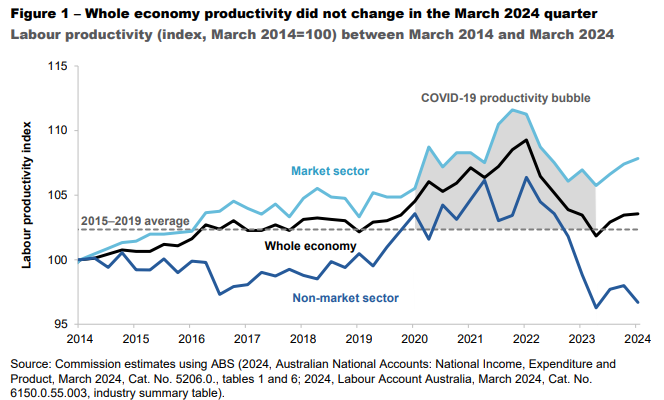

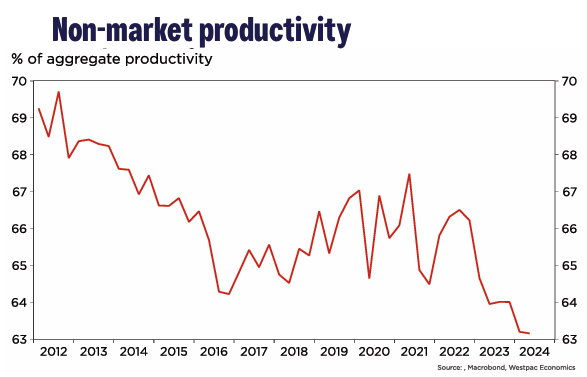

As I keep highlighting, the explosion in non-market jobs has both budgetary and productivity implications for Australia since they are funded largely via tax revenues, and the non-market sector has historically exhibited far poorer productivity growth than the market sector:

The expansion in public spending, therefore, necessarily means slower productivity growth for Australia:

The question follows: where will Australia’s future productivity growth come from?