Jarden economist Anthony Malouf says the investment bank has concluded that increased government spending on the $49 billion National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) is contributing to inflation and could reduce the chances of the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) cutting interest rates.

Jarden attributes the increased spending on the NDIS to the jump in the number of children joining the NDIS for developmental delays, with 43% of the NDIS’s 650,000 participants under the age of 14.

“Whilst it is clear that there is a strong need for the NDIS, we find that the macroeconomic impacts of the rise in disabilities and NDIS spend are added pressure to already elevated government spending measures which could have inflationary impacts”, Jarden economist Anthony Malouf said.

“It is clear that government spending decisions could have inflationary impacts”.

“We highlight this as a key risk moving forward, particularly as the RBA tries to rein in inflation”, he said.

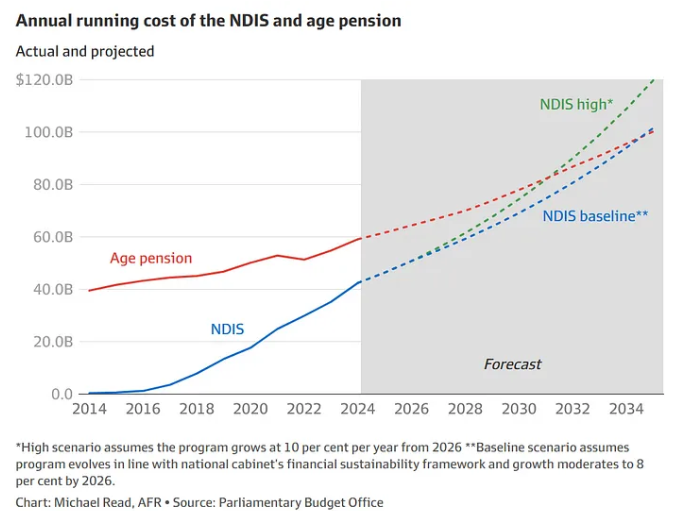

Despite being under a decade old, the NDIS already costs taxpayers more to run per year than the aged care system ($36 billion), Medicare ($32 billion), federal government funding for hospitals ($30 billion), and the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme ($20 billion).

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) also anticipates that by 2030, the NDIS will surpass the age pension as the most expensive area of government spending.

Economist Steven Hamilton also told The AFR that the NDIS has grown from 0% of GDP to 2% of GDP in only a decade.

“In ordinary times, such a massive surge in public spending would put pressure on the economy, but with the economy operating beyond its capacity, it will have meaningfully contributed to the inflation crisis”, Hamilton said.

“Setting aside the obvious merits of caring for people with disabilities, drawing away such a large share of the economy’s resources to what are economically unproductive activities will have meaningfully contributed to our big slowdown in productivity”.

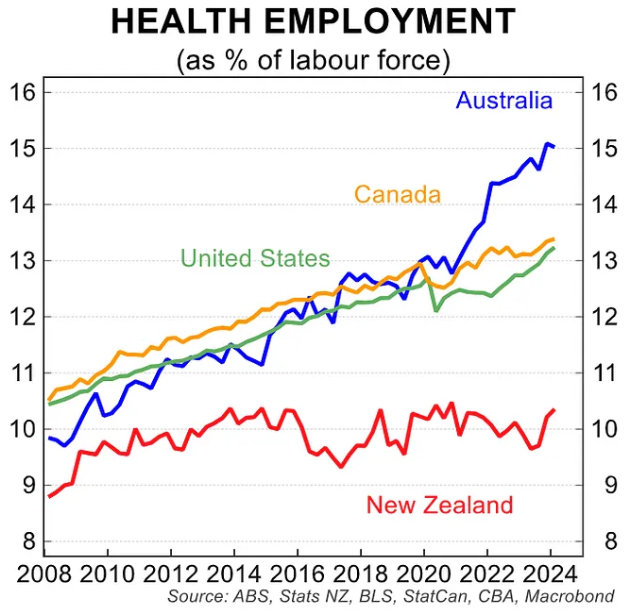

The following chart from CBA shows the explosion of healthcare & social assistance jobs in Australia relative to comparable Anglo nations:

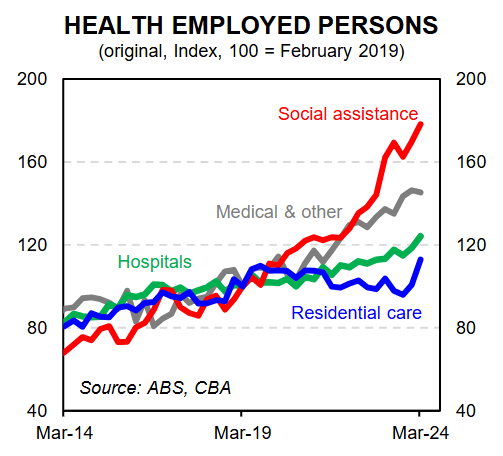

Most of these new roles have been caring jobs in the social assistance category:

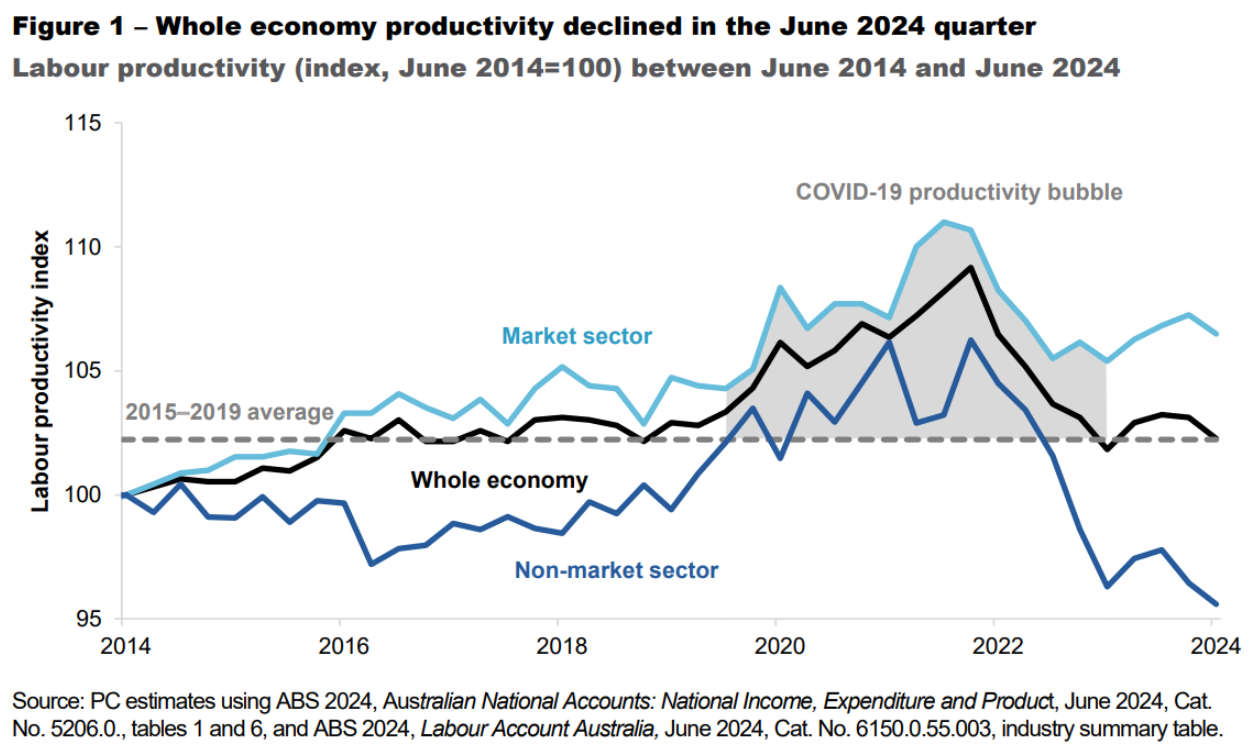

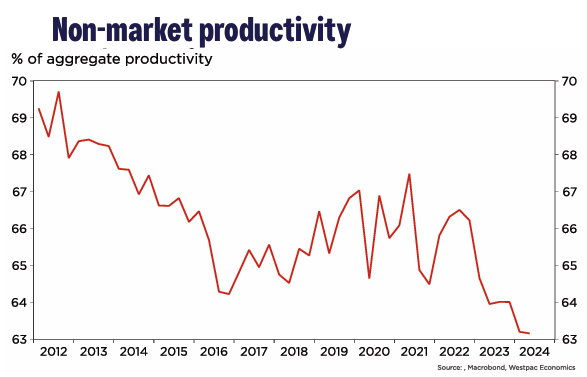

As noted by Hamilton, the surge in NDIS jobs would have contributed to Australia’s productivity slowdown, since non-market sector jobs are less productive than market-based jobs:

Therefore, the expansion of the NDIS necessarily means slower productivity growth for Australia.

Millions of Australians haven’t just found out that they are disabled.

Rather, a massive fiscal incentive has driven an entire industry around the disabled.

New terms like “neurodivergence”, “ADHD,” “spectrum”, and others have emerged to describe disabling conditions.

I am certainly not claiming that these conditions do not exist. Of course they do.

However, many of today’s disabilities were previously common “anxiety” or introversion, and were not treated with costly interventions funded by the taxpayer.

On the supply side, we have seen private equity firms, billionaires, and even organised criminals abusing the system.

Earlier this month, The Australian reported that there are around 170,000 NDIS providers at present, with about 150,000 of them currently operating without oversight. How has this been allowed to happen?

With a honeypot of nearly $50 billion on offer, the NDIS was bound to attract shady players, necessitating strict regulation and control.

In this respect, the NDIS was built to fail from the start.

Every time the federal government has established a privatised market with a large sum of money on offer, there has been extensive rorting, misuse, and waste.

We saw extensive abuse of the private vocational education and training (VET) system, the pink batts program, and child care subsidies. The NDIS is merely the latest example.

The plague of disability alongside the ballooning cost of the NDIS cannot be ignored.

As more resources are drawn into the NDIS, the economy will become less dynamic and income-generating.

The entire NDIS sector is dependent on other sectors to bear the deadweight loss, as well as public borrowing.

How will the NDIS be funded to the tune of $60-70 billion over the next five years, given that national income will be in freefall with commodity prices?

These are legitimate questions that must be answered by policymakers.