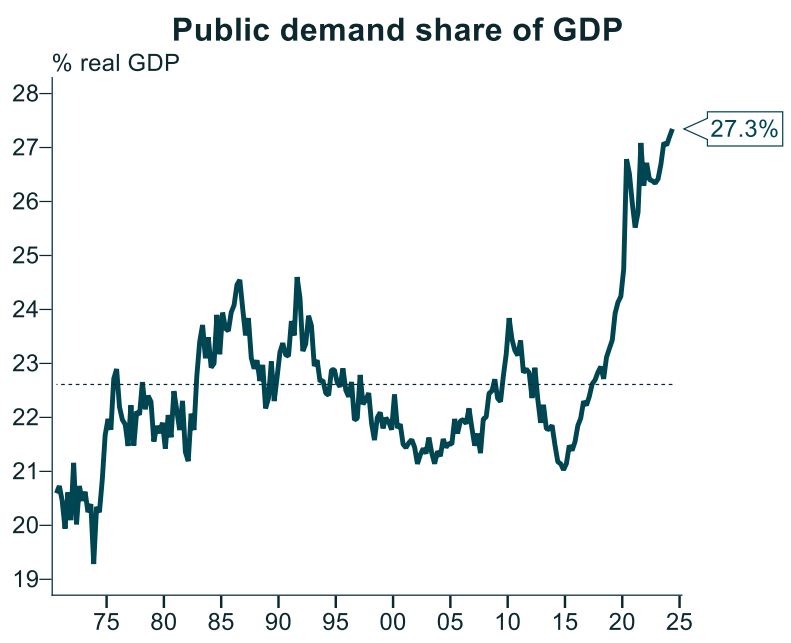

Treasurer Jim Chalmers was busy claiming that record federal spending has kept the economy out of recession.

Source: Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

“I’m old enough to remember when government’s budgets helping to avoid recession was seen as a good thing”, Chalmers said.

“We’re going for a soft landing in the economy. Our political opponents really want to see a hard landing in our economy. And they want interest rates to kind of clean up the mess afterwards”.

“They basically want to see a crash, and then to sweep up afterwards. We want to avoid the crash in the first place”, he said.

Chalmers is right in one sense. Australia’s real GDP grew by 0.2% in Q2, with the public sector contributing around 0.4% of that growth.

The public sector grew by 1.5% in Q2, whereas the private sector declined by 0.6% over the quarter.

Therefore, the overall economy would have declined by around 0.2% if not for the record public sector spending.

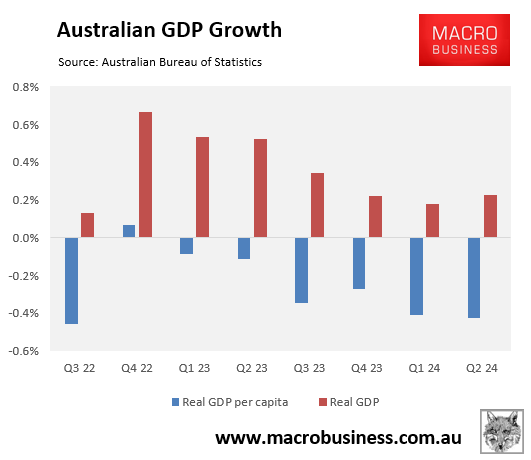

The situation is obviously much worse in per capita terms and worse again for Australian households.

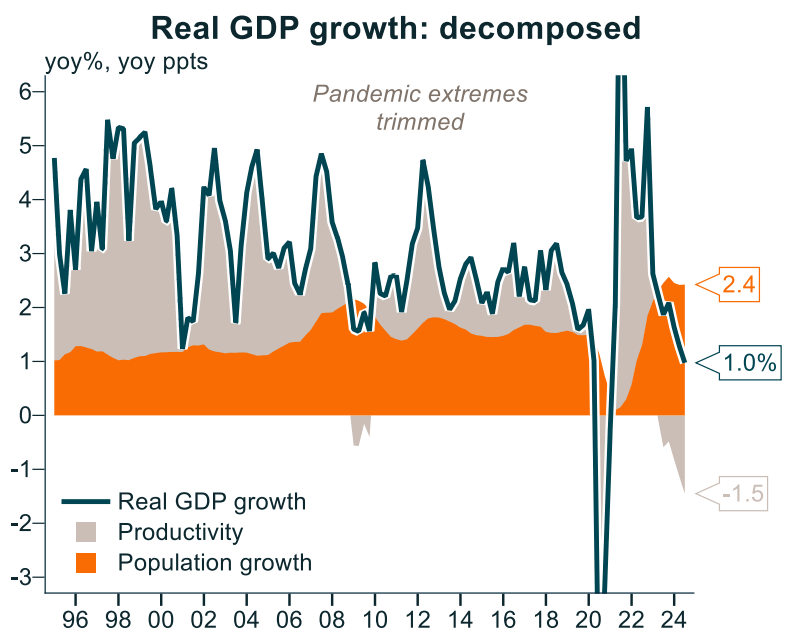

Source: Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

Real per capita GDP shrank by 0.4% in Q2 and has declined for six consecutive quarters and for seven of the past eight quarters.

In fact, Australia’s per capita GDP was 2.0% lower in Q2 2024 than it was in Q2 2022 when the Albanese government came to power.

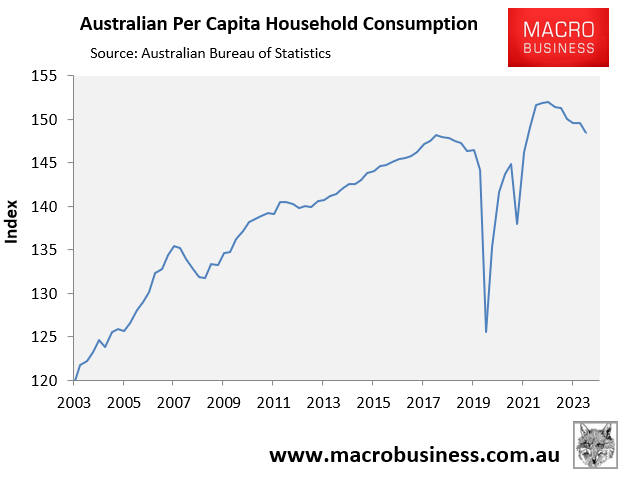

Australian households have been hit especially hard.

Household spending per capita has now contracted for six consecutive quarters, down 2.4% over that period:

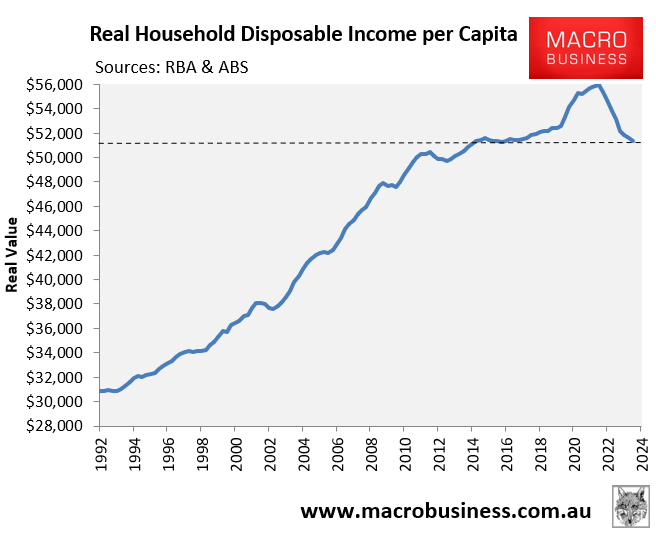

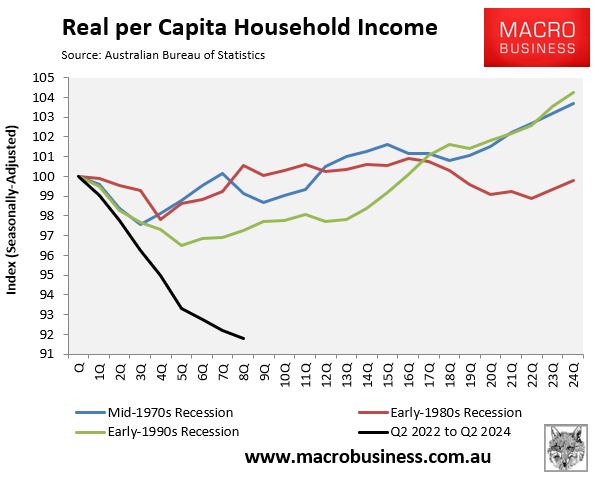

Even worse, real per capita household disposable income is now tracking 8.2% below its Q2 2022 peak. This represents one of the largest declines in the world:

It also represents the deepest decline in household disposable income in recorded Australian history:

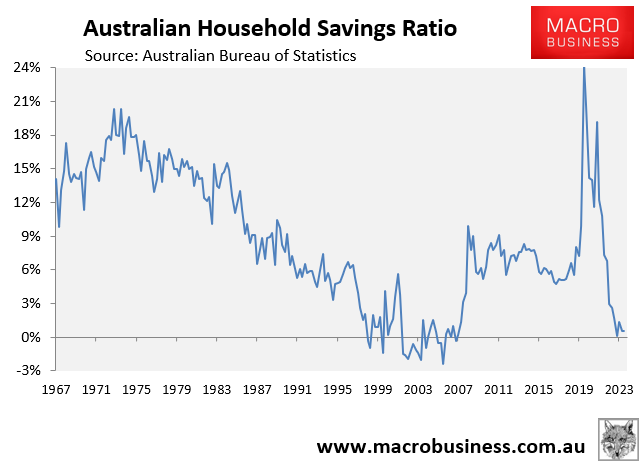

The only reason why household consumption didn’t fall even further is that the household savings rate has collapsed to just 0.6%. This suggests that households have drawn down their pandemic savings [Note: the savings rate is almost always positive due to compulsory superannuation contributions, which are counted as savings but not available for consumption].

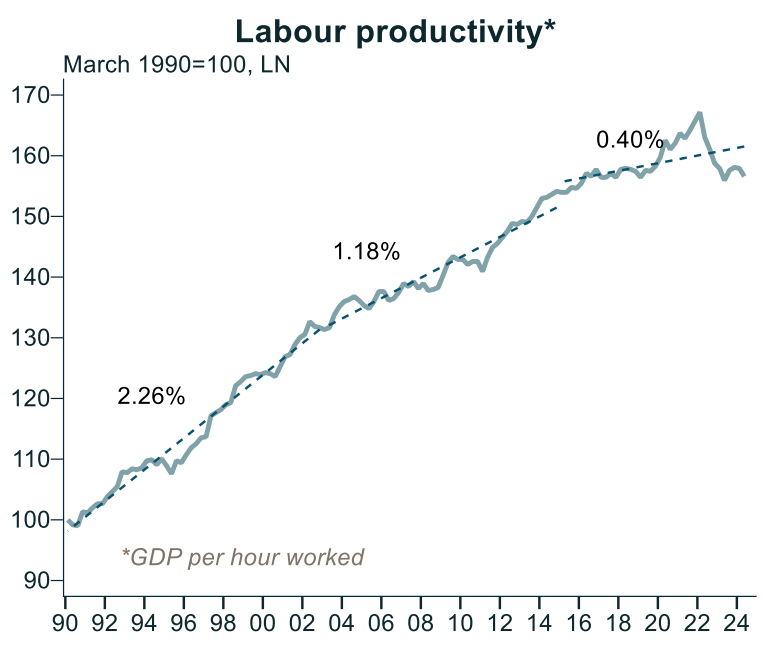

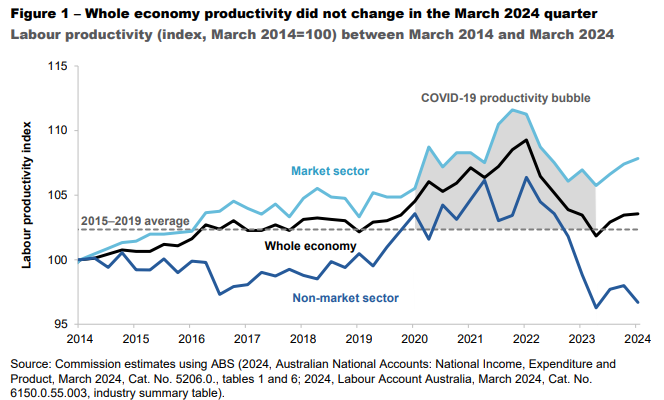

It is also worth noting that Australia’s labour productivity is deplorable, falling by another 0.8% in Q2 to be tracking around levels prevailing in 2017:

Source: Alex Joiner (IFM Investors)

Much of this productivity decline can be traced back to the record growth in non-market jobs, alongside the surge in net overseas migration.

In short, the Q2 national accounts showed a Ponzi economy that was growing slowly via extreme immigration-driven population growth and government spending, but where individual households’ slice of the pie is shrinking at a record rate.

Finally, given that the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) is trying to slow aggregate demand via interest rates, the record government spending means that interest rates will need to remain higher for longer, which negatively impacts household disposable income.

Thus, a softer landing for the economy means a harder landing for households.