The Australian’s Stephen Matchett has written an interesting article on the barriers Australian universities face when opening campuses offshore.

It comes after Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan announced that the government would spend $5 million to help local universities establish overseas campuses and avoid the federal government’s international student quotas.

Matchett notes that only 7% of international students enrolled in Australian courses are outside Australia.

The following reasons are given for the low numbers of overseas enrolled students:

- Limited appetite for setting up overseas and competing with local institutions.

- Australian cost structures in low-income countries make margins thin.

- Students are unwilling to pay Australian prices to learn locally. “There is a chasm between Australian university costs and what Indians will pay at home”, Matchett says.

- India’s national education regulator explicitly rules out low-cost online courses.

- Setting up campuses offshore is expensive, and expatriating profits can be difficult.

- International campuses generally do not make money and are not financially viable.

These above reasons are probably true. However, Matchett has missed the number one reason why overseas campuses fail: because most international students want to work and live in Australia. And without the carrot of work rights and residency, there is little point of studying at an Australian institution.

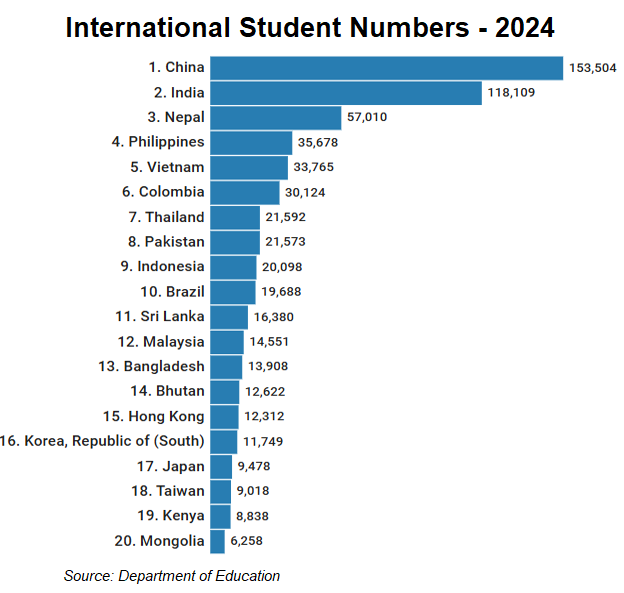

Take a look at the following chart plotting international enrolments in Australia by source country:

As you can see, Australia’s international student intake is heavily weighted towards South Asia (i.e. India, Nepal, Pakistan, Bangladesh, and Bhutan).

South Asia is also the fastest growing source region for international students coming to Australia.

A recent Navitas poll of study intentions showed that students from South Asia chose a study destination based on their ability to obtain work rights, a low-cost course, and permanent residency.

South Asian students care about immigration, not education quality.

As noted by Associate Professor Salvatore Babones’ in his latest book “Australia’s Universities, Can They Reform”:

“For many South Asian students, a student visa is a very expensive but thinly disguised work visa”.

In fact, with the exception of students from China and Europe, all source countries place a high importance on the ability to work while studying and post-study job options.

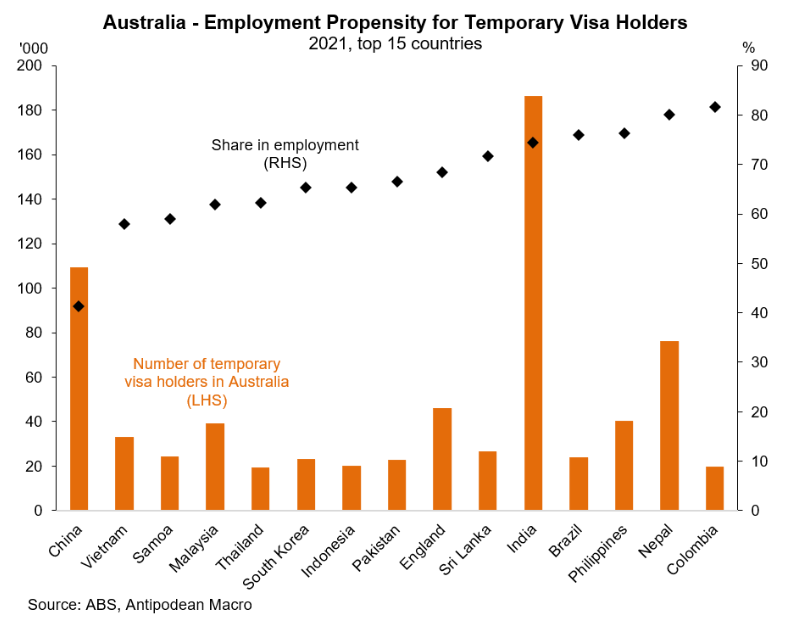

This conclusion is supported by the following chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro, which shows that Chinese temporary migrants are far less likely to be employed than temporary residents from other nations.

The above analysis explains why international education is essentially a people-importing immigration industry rather than a legitimate export sector.

In most cases, student visas are disguised as low-skilled work visas.

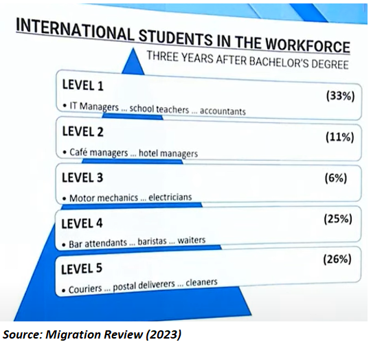

The same is true for international graduates who have finished their education. According to the Migration Review, 51% of international graduates with bachelor’s degrees who had lived in Australia for three years held low-skilled occupations:

These are also likely to be the ‘cream of the crop’ because most graduate visas are only valid for two years. Therefore, the lowest-quality international graduates had most likely already returned home.

The reality is that limiting employment rights and opportunities for permanent residency would drastically reduce the number of students arriving from non-Chinese source countries, because that is their primary goal of “studying” in Australia.

It follows that the only way that overseas campuses of Australian universities could ever take off is if the federal government permitted graduates to work and live in Australia post study.