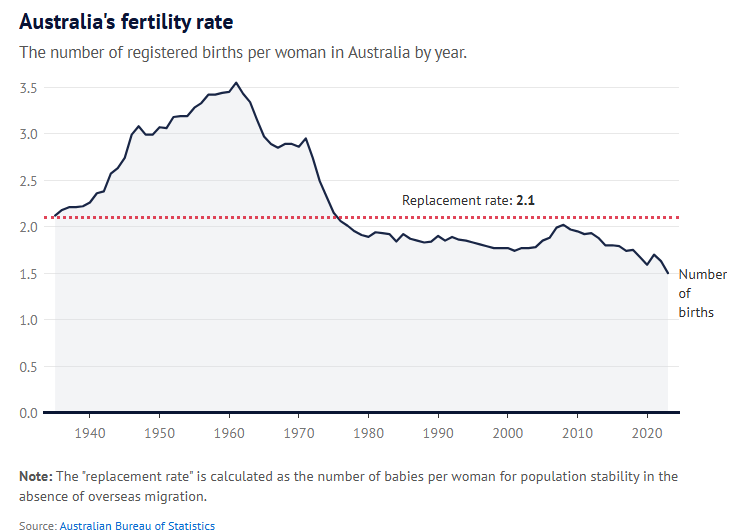

The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) this week released data showing that Australia’s birth rate has collapsed to an all-time low of 1.5 babies per woman:

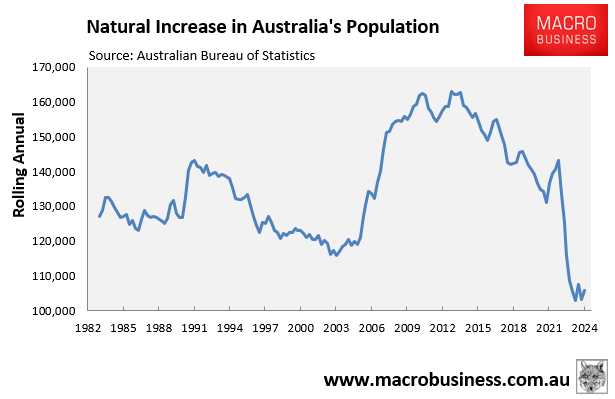

The collapse in births combined with a rise in deaths meant that Australia’s population only grew by 105,600 in the year to March 2024 from natural increase:

The SMH pinned part of the blame for Australia’s collapsing birth rate on “high housing costs and the expense of bringing up children”.

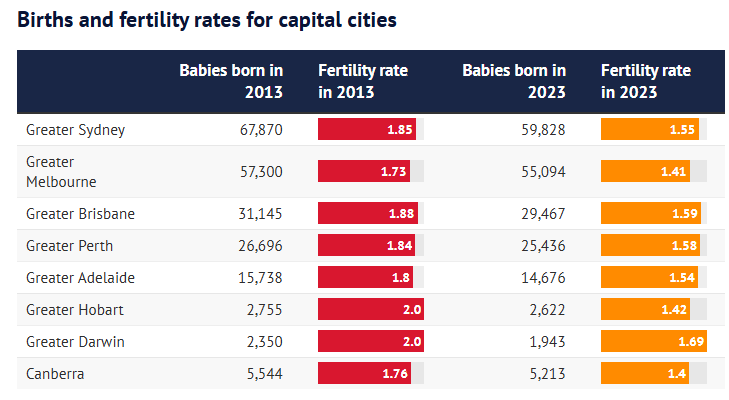

“The epicentre of the collapse is Sydney where the number of births has slumped by 14% since 2018, coinciding with a 50% increase in the city’s median house price”, The SMH wrote.

The following table from The SMH shows the change in fertility rates across capital cities over the decade to 2023:

Source: The SMH

Pro-Big Australia mouthpiece, ANU demographer Liz Allen, shed crocodile tears for young Australians locked-out of affordable housing and from having a family.

“We have young people who say they want to have a child, or a subsequent child, but the barriers in front of them are insurmountable. The rug is being pulled from beneath their futures”, she said.

“Housing affordability, economic insecurity, gender inequality and climate boiling – that’s a recipe for the most effective contraceptive ever”.

Dr David Knox, an actuary and senior partner at consulting firm Mercer, acknowledged that the significant drop in Australia’s birth rate “reflects economic pressures” including the rising cost of housing.

“Having babies costs money, mortgages are costing more, so I think the cost-of-living pressures are causing people to put off having babies”, he said.

Know also said that the drop in birth rate means “we are going to want skilled migrants in this country”.

“There will be increasing competition for skilled migrants around the world, whether it’s in Canada or the US or even China”, he said.

However, there is also a negative feedback loop in play with immigration given that it is a key driver of the surge in house prices and rents and is forcing families to live in shoebox apartments.

As a result, there is a decrease in fertility rates, which government policies then backfill via immigration.

According to HSBC research published in January, “a 10% increase in house prices leads to a 1.3% drop in birth rates, and an even sharper fall among renters”.

Last month, the NSW Productivity and Equality Commission called on governments to deregulate housing supply to allow for the construction of higher towers, smaller apartments, less storage and natural light, smaller balconies, and fewer car spaces:

NSW Productivity and Equality Commission claimed that these reforms could lower rents by around 10%, thereby improving affordability, but at the cost of amenity.

Tiny high-rise shoebox apartments with no parking, limited storage, limited natural light, or balconies are clearly not conducive to raising a family.

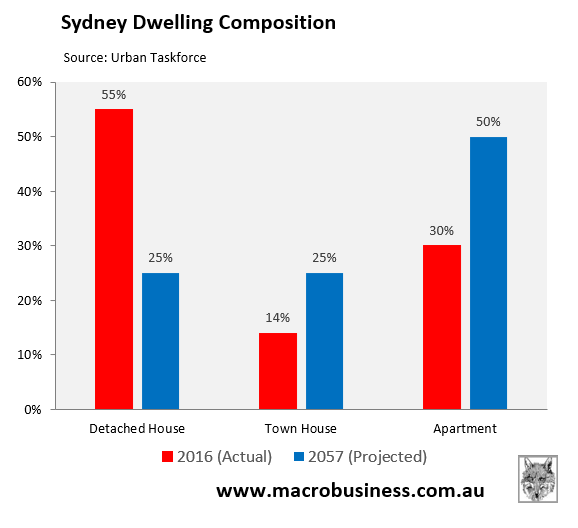

Immigration-driven population growth has affected (and will continue to transform) the composition of our major capital cities’ housing stock, shifting from family-friendly houses with backyards to family-unfriendly one- and two-bedroom high-rise apartments.

Liam Davies, an urban planning specialist at RMIT University, recently cautioned that if Australia does not figure out how to supply more three- and four-bedroom apartments catering to families in inner and middle metropolitan locations, cities will become “very separated”.

“I think that’s a problem that we’ve got — family homes aren’t being built in apartments in inner and middle suburbs — they’re still standalone, separate housing in the outer suburbs and in the growth areas”, he said.

“Middle-income Australians won’t be able to raise families in family homes in the inner and middle suburbs. They’ll be increasingly forced further out”.

Policies around immigration and housing discourage Australians from having children.

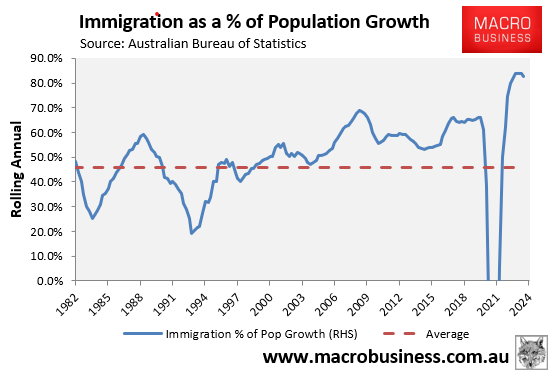

However, rather than addressing the underlying issue, the federal government has compensated for the declining birth rate by increasing net overseas migration to unprecedented levels.

As a result, the government has made housing more cramped and expensive, while also making jobs less secure for young Australians of childbearing age.