On Wednesday, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released quarterly data on dwelling commencements and completions.

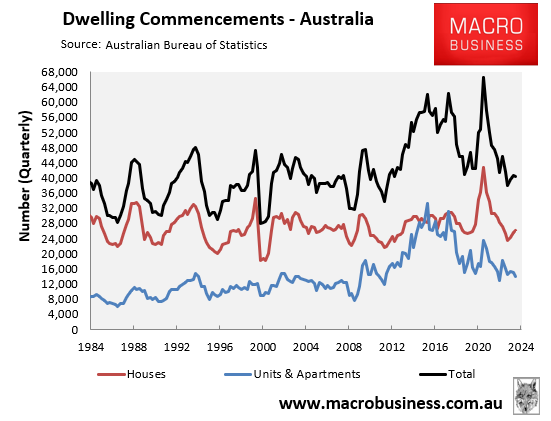

Over the June quarter, 40,300 dwellings commenced construction, nearly one-third below the Albanese government’s five-year 1.2 million housing target, which requires 60,000 dwellings to be constructed every quarter.

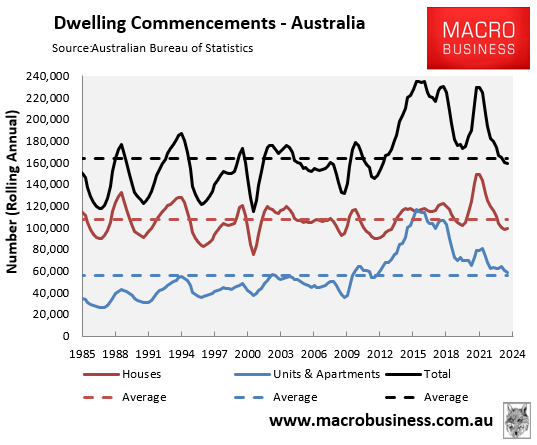

In the 2023-24 financial year, only 158,750 dwellings commenced construction, 81,250 (34%) below Labor’s target, requiring 240,000 homes to be built annually.

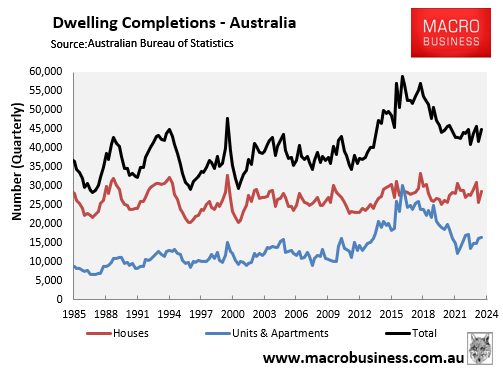

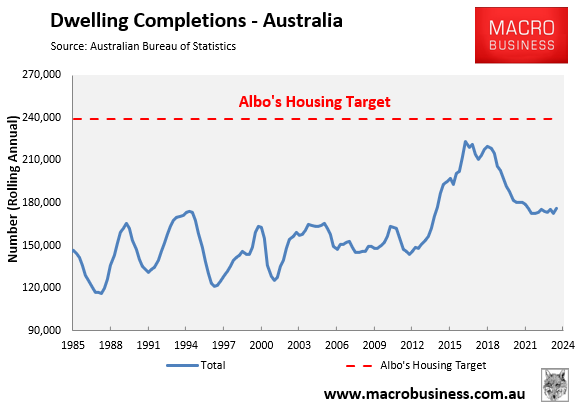

The news was slightly better for dwelling completions, where 44,900 homes were completed over the quarter, still 15,100 (25%) below the quarterly run rate of 60,000 required to meet Labor’s housing target.

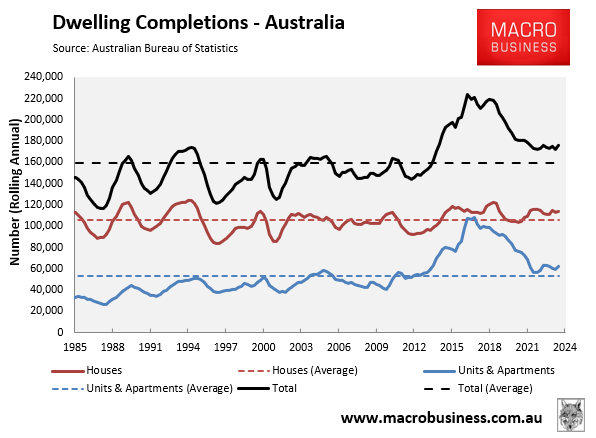

In the 2023-24 financial year, 176,100 homes were completed across Australia, 63,900 (27%) less than the 240,000 required to meet Labor’s housing target.

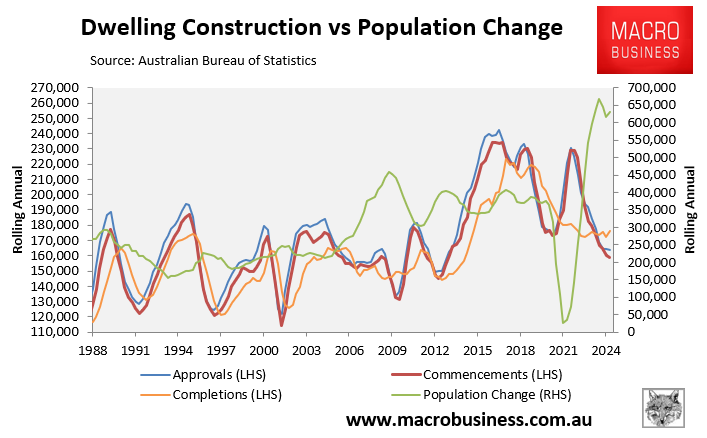

The next chart plots annual dwelling approvals, commencements and completions against population growth and shows how housing supply is failing dismally to keep pace with extreme population demand.

Over the most recent 12-month period:

- 166,200 dwellings were approved for construction, 78,800 (31%) below Labor’s housing target.

- 158,750 dwellings commenced construction, 81,250 (34%) below Labor’s target.

- 176,100 homes were completed across Australia, 63,900 (27%) below Labor’s target.

- Australia’s population grew by 631,300 (as implied by the Q2 national accounts).

Finally, the following chart illustrates the gaping gap between actual construction and Labor’s targeted level:

There is zero likelihood of getting anywhere near Labor’s 1.2 million housing target given:

- Interest rates are likely to remain structurally higher than they were at last decade’s construction peak.

- Construction costs are around 40% higher than they were pre-pandemic.

- Builders are competing for labour and materials against government big build infrastructure projects.

- Thousands of home builders have collapsed.

Therefore, the only realistic solution to Australia’s housing shortage is to dramatically slow net overseas migration to a level below the capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing crisis will become permanent.