For years, MacroBusiness has argued that Australia’s productivity has been stifled through “capital shallowing”, which occurs when infrastructure and business investment fail to keep pace with population growth.

The result is less capital per worker, rising congestion costs, lower productivity growth, and lower per capita GDP growth.

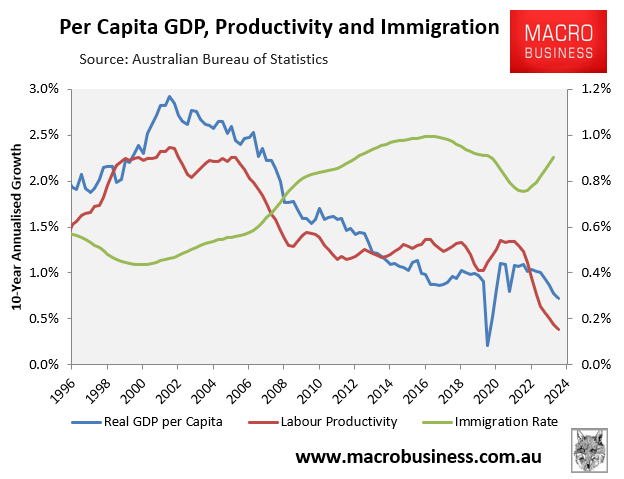

The following chart shows Australia’s long-run trend per capita GDP growth against labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) and the immigration rate (net overseas migration as a share of the population):

Australia’s GDP per capita and productivity growth collapsed after net overseas migration dramatically increased from 2005.

The above chart displays a negative correlation between net overseas migration and productivity and per capita GDP growth.

A new bulletin from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), entitled Productivity in the post-pandemic world: old trend or new path?, claims that part of Australia’s productivity slump can be explained by investment failing to keep pace with strong net overseas migration.

“The investment response in Canada and Australia has lagged growth in the labour force”, the Bulletin said.

“Capital shallowing due to chronic investment weakness has been one reason behind the widely documented pre-pandemic slowdown in productivity growth”.

The BIS also warned that weak productivity growth could deliver high inflation alongside sluggish economic growth.

“In the near term, sluggish productivity growth could delay the convergence of inflation to central bank targets”, the BIS notes.

“In the longer term, persistent weakness in productivity means lower potential growth”.

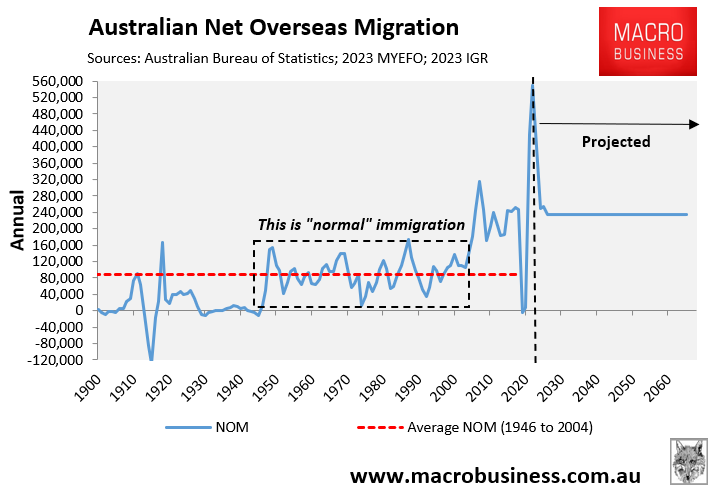

Recall that Australia’s population is officially projected to grow by more than 13 million (~50%) over the next 39 years, driven solely by ongoing high immigration:

The projected population increase is the equivalent of adding another Sydney, Melbourne, and Brisbane to the country’s current population in just 39 years.

Massive amounts of business and infrastructure investment and services and more water and energy resources will be required to accommodate such rapid population growth.

There is absolutely no chance that enough investment will be provided—look at the last 20 years—meaning that capital shallowing will continue, congestion costs will rise, and productivity, per capita GDP growth, and living standards will fall.

Australia’s immigration “Ponzi” economy is a literal recipe for decades of economic stagflation.