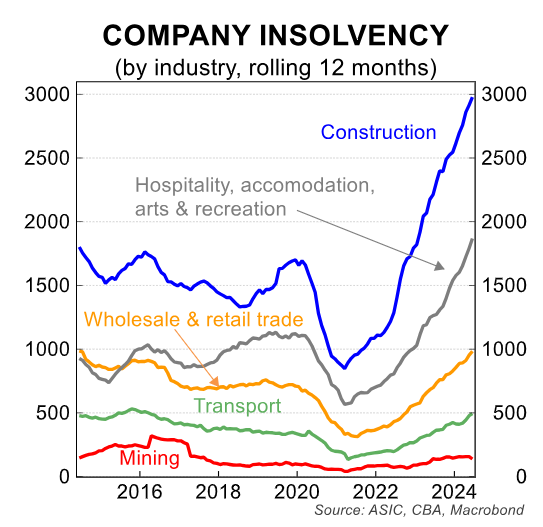

According to insolvency data from the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC), over 1,900 hospitality businesses failed last financial year as food and energy costs rose and discretionary consumer spending fell.

The accommodation and food services sub-sector experienced a 50% rise in insolvency appointments last financial year to a record 1667, surpassing the previous high of 1114 in 2023.

An analysis from The Australian revealed that more than 90,000 jobs have been lost in the hospitality industry over the past year.

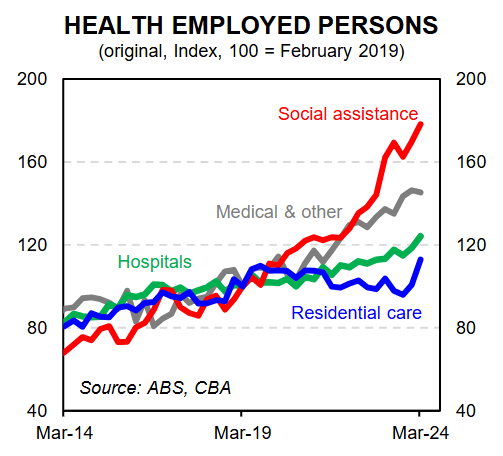

However, these workers have been absorbed by the care economy, where job growth is booming on the back of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS).

Over the last financial year, 171,000 jobs were filled in healthcare and social assistance, according to The Australian.

Australian Hotels Association chief executive Stephen Ferguson said that part of the reason why the number of jobs in the hospitality industry has fallen is because workers were leaving for other sectors, particularly the care economy.

Uber Eats Australia managing director, Ed Kitchen, said that Australia’s hospitality sector faced “a collision” of challenges.

“In our conversations with restaurants, there doesn’t seem to be a singular factor they isolate, but rather … several themes including higher rental costs, competitive pressures, supply chain issues, growing insurance premiums, increasing utility and wage bills, and more expensive raw products”, he explained.

Restaurant and Catering Association CEO Suresh Manickman agreed, explaining that the “unprecedented fusion” of pressures “have created one of the most challenging economic landscapes in recent history … impacting the ability for the sector to operate”.

Restaurant and Catering Australia predicted that one in eleven hospitality businesses will fail over the coming year.

In my opinion, Australia’s hospitality sector needs to downsize, especially the number of cafés.

When I moved to Melbourne’s Ashburton in 2006, my local High Street shopping strip contained about four cafés, which was sufficient.

Over the next 18 years, the number of cafés on or near High Street increased to more than a dozen, with the majority of them remaining empty most of the time.

The story is similar across Australia, where the number of cafés has grown unsustainably.

While a few cafés prosper and remain busy, the majority fail to break even.

Before the pandemic, there were too many cafés to accommodate demand. And, given the cost of living has risen, many cafés will have to close.

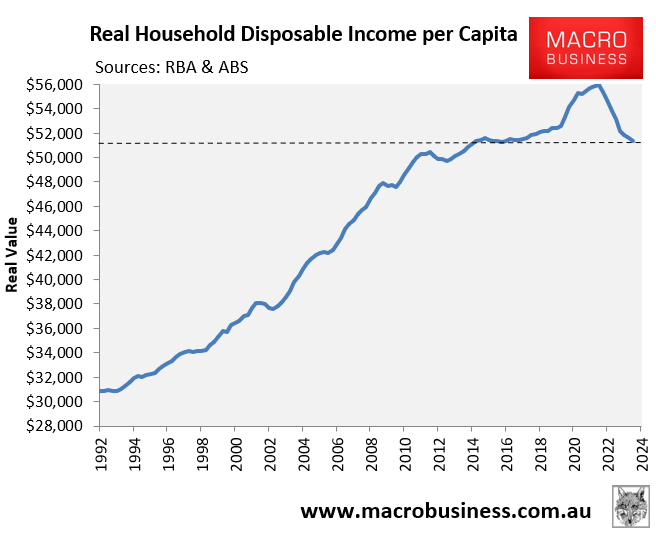

Given the exorbitant cost of mortgage and rent payments, as well as the considerable decline in real household disposable incomes over the last two years, who can afford $5, let alone $7, for a lukewarm coffee?

Financially stretched Aussies are increasingly preparing coffee at home or purchasing machine-made coffee for $2 at a service station or 7-Eleven.

Australia functioned perfectly well with half the number of cafés. It will do so again.