Escalating costs are arguably the greatest barrier to meeting the Albanese government’s target of building 1.2 million homes over five years.

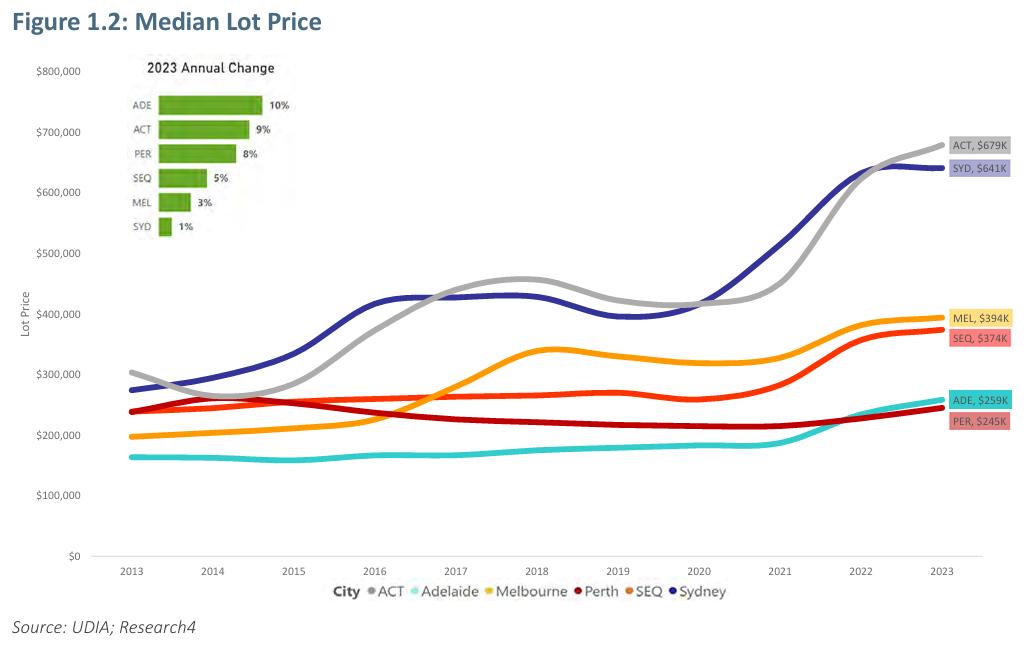

The Urban Development Institute of Australia’s (UDIA) 2024 State of the Land report showed that Greater Sydney’s median lot price was $641,250 as of Q4 2023, Greater Melbourne’s was $394,250, South-East Queensland’s was $374,250, Perth’s was $245,250 and Adelaide’s was $258,560.

As shown above, all major capitals have experienced significant land cost inflation since the beginning of the pandemic in early 2020.

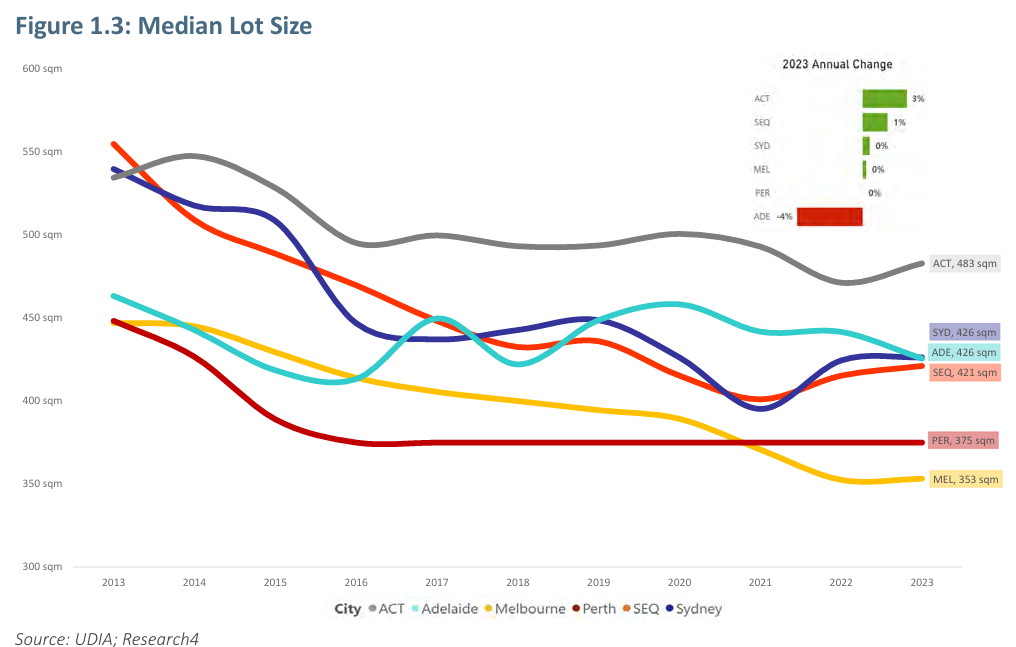

Not only have lot prices risen, but the size of the blocks has decreased too:

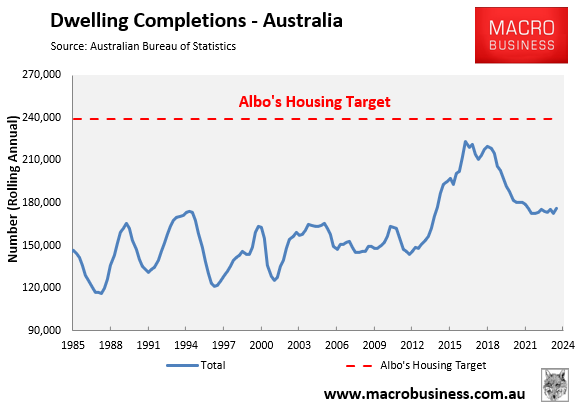

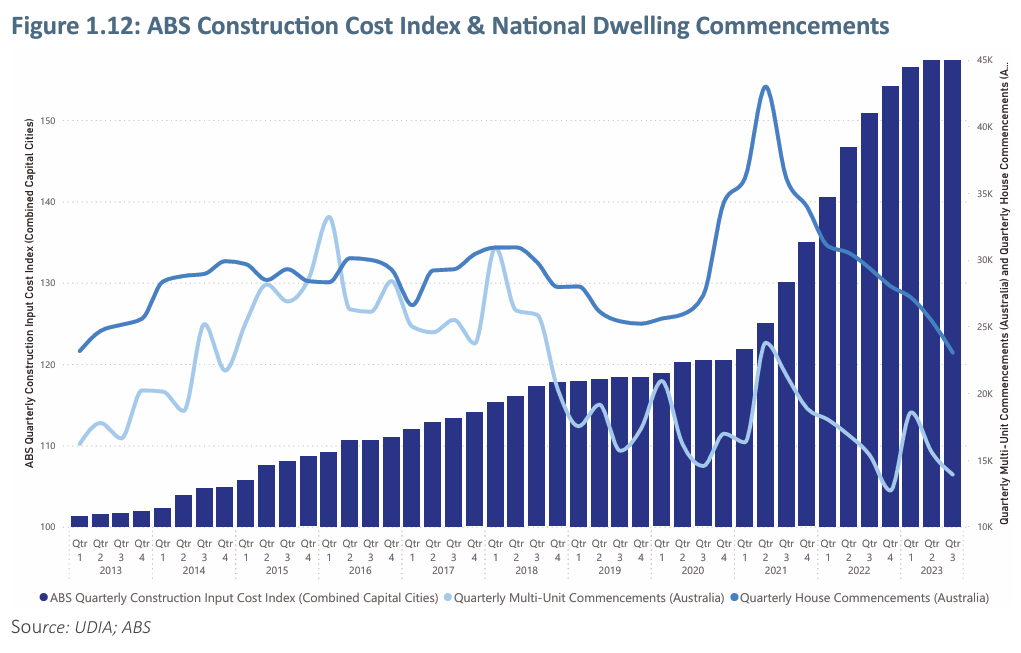

The cost of building a house on the inflated lot has also surged by nearly 40% since the start of the pandemic, which is clearly having a negative impact on construction rates:

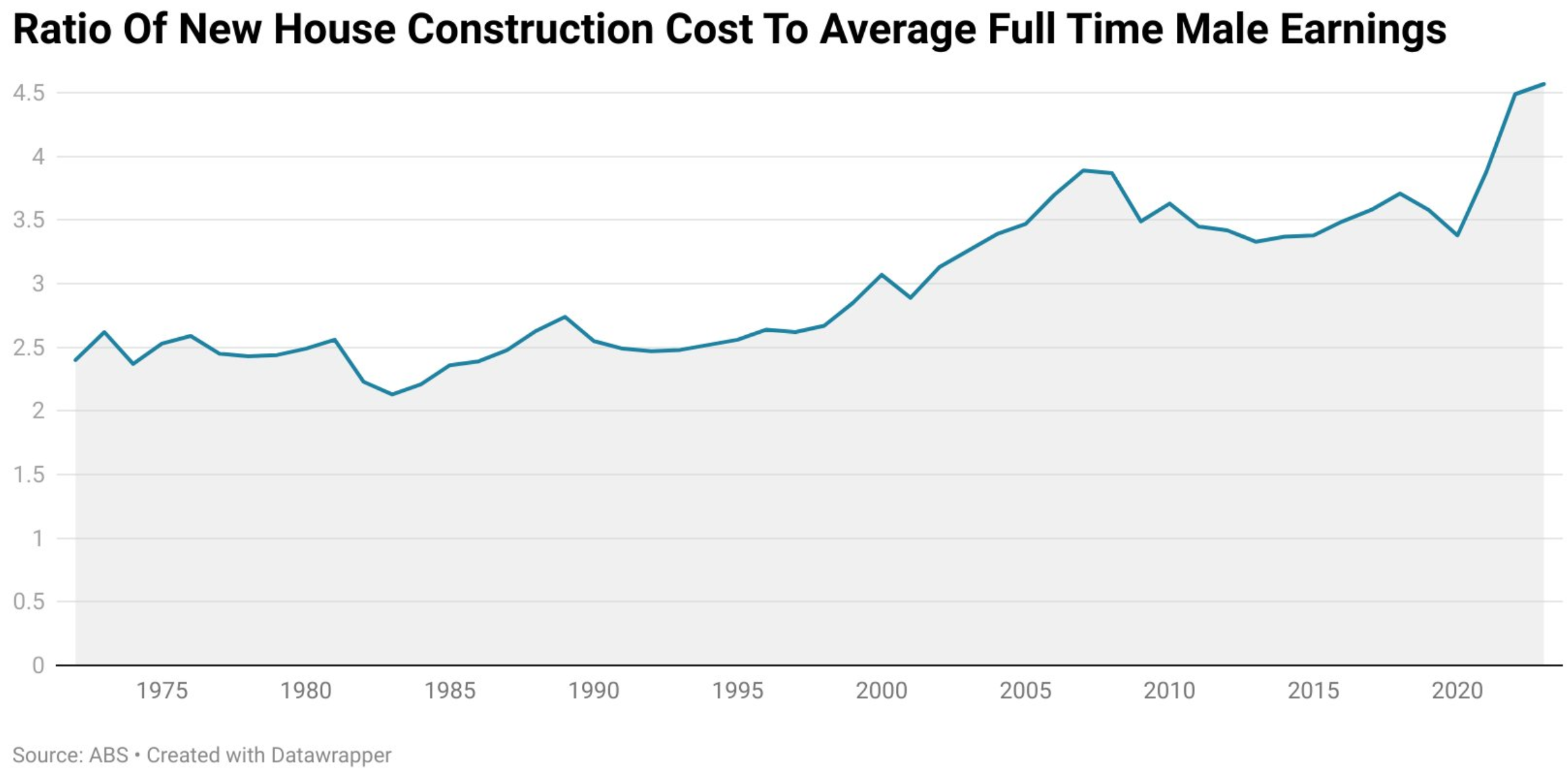

According to independent economist Tarric Brooker, “part of the reason why housing construction keeping up with demand in Australia will be challenging in the coming years is cost”.

“The average cost to build a new house is now over 4.5x average male FT earnings and that is just the build, no land, no infrastructure, nothing else”, Brooker noted on Twitter (X):

Separately, Brooker noted that “between the national median new land price and the average cost of constructing a new house, a new house now costs over $800,000”.

“I suspect we may have reached a tipping point, where home construction may not fully recover for a decade or more”.

Tarric Brooker is right, of course. The cost of purchasing a lot and building a new home is now structurally much higher than it was before the pandemic.

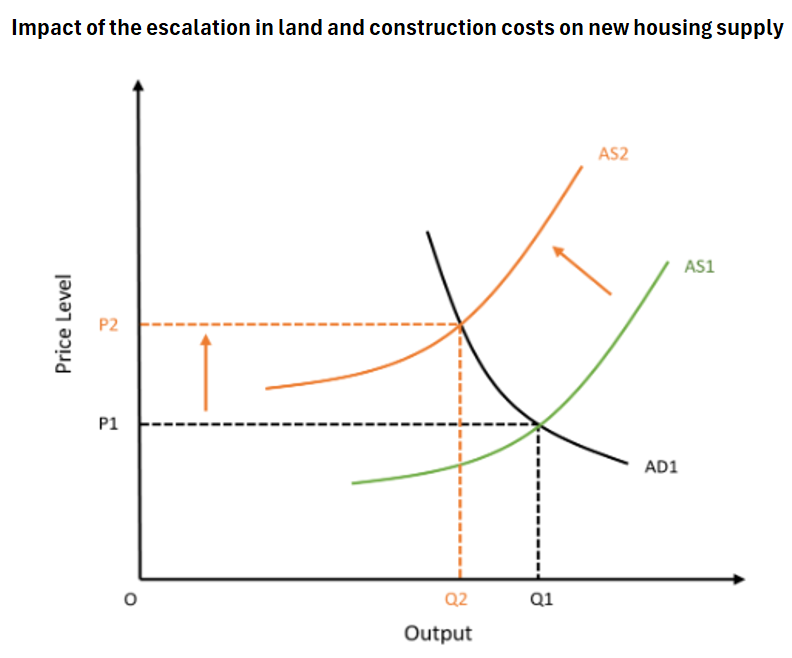

In economic terms, this cost-push inflation has caused a shift in the aggregate supply curve to the left, reducing overall capacity for producing homes at every price tier:

A large number of home builders have also collapsed in recent years, reducing the nation’s capacity to build homes, as has the loss of tradies and labourers to government infrastructure projects.

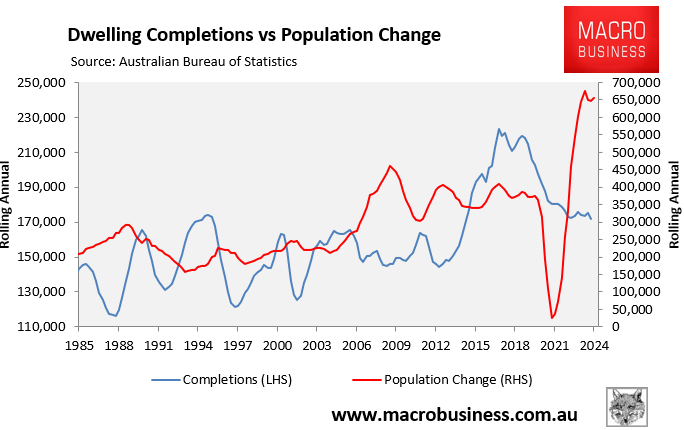

In short, Australia’s construction capacity has been reduced, meaning that we are likely facing a prolonged period of stunted housing production.

Therefore, the only realistic solution to easing the nation’s housing crisis is to temper demand by cutting immigration to a level below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

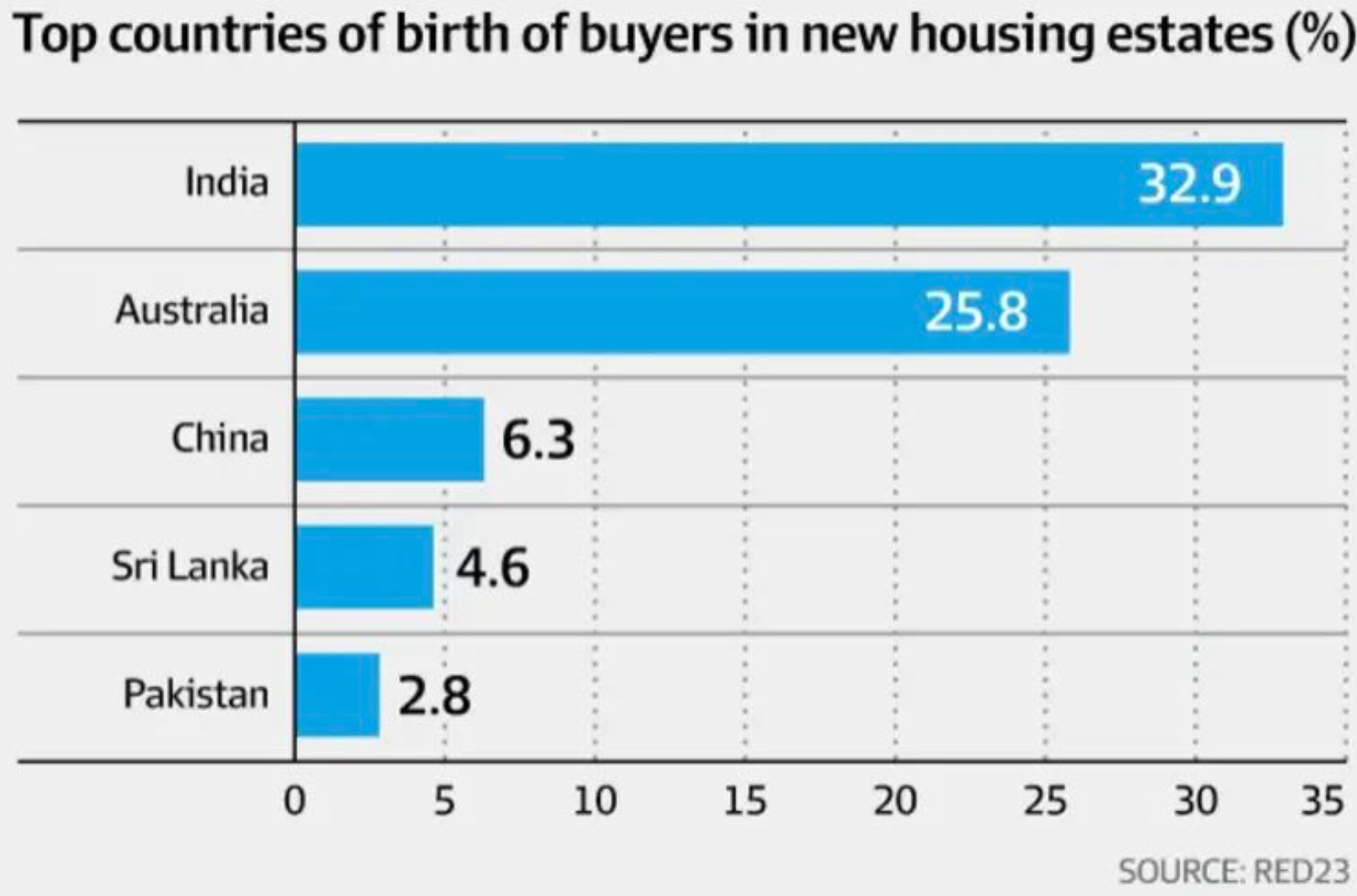

After all, most of the demand for new housing comes from migrants: