Following a strategic review of the student visa program in 2011 (the “Knight Review”), the Gillard government significantly enhanced employment rights for graduate (485) visas in 2013.

In particular, 485 visa holders were not needed to meet skills shortage requirements and were allowed to stay in Australia for two to four years after finishing their studies, as opposed to the prior 18 months.

In contrast to temporary skilled shortage (TSS) visas, holders of graduate (485) visas were not required to be qualified for any of the jobs on the Skilled Occupation List.

They did not require a solid offer of employment from a firm.

They were not required to receive a minimum rate of pay.

They also did not have to find a job that matched their qualifications or required a specific degree of expertise.

Their visa also remains valid even if they are unable to find work.

The Knight Review strongly advocated for expanding post-study work rights (PSWR) since it would significantly boost Australia’s appeal as a destination for international students, helping Australian universities and employers.

Australia’s graduate (485) visas are now regarded as among the most appealing worldwide, granting full employment rights. They are also highly coveted by international students since they are viewed as a means to permanent residency.

As Peter Mares explained in 2013:

Knight stated plainly that an expanded work visa was essential to “the ongoing viability of our universities in an increasingly competitive global market for students.” Vice-chancellors also made the connection explicit.

At the time, Glenn Withers, chief executive of Universities Australia, said that Knight’s “breakthrough” proposal was as good as or better than the work rights on offer in Canada and the United States.

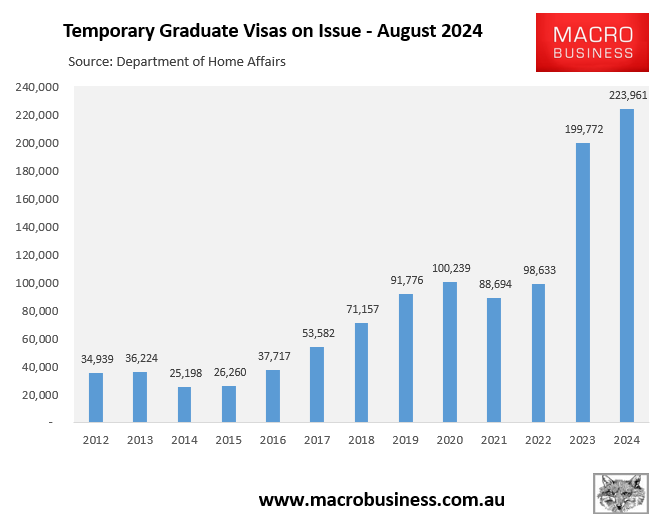

As a result, international education was rapidly transformed into an immigration industry and graduate visa numbers soared from around 36,000 in 2013 to 224,000 currently:

A classic example of international education masquerading as immigration was on display this week, with international students and advocacy groups protesting against the government’s decision to cap the age limit for temporary graduate visas to 35:

Graduate visa holders protest against age limits. Source: SBS News.

“On Friday, October 11, international students across Australia held a Vigil of Hope to protest recent changes to the Temporary Graduate (485) visa”, SBS reported.

“The changes, which include an age cap of 35, are expected to impact approximately 20,000 students, many of whom fear being forced to return to their home countries once their visas expire”.

“We don’t deserve to be singled out because of our age! Australia, you need us! You need my skills!” said JC Coca, a speaker at the event.

The last time that I checked, student visas were temporary, meaning that holders were supposed to return home at the completion of their studies. They were never an automatic pathway to residency.

Second, speaker JC Coca’s claim that Australia needs their skills is laughable, given international graduates typically work in low-skilled jobs.

Two years ago, academics Ly Tran and George Tan warned that graduate (485) visas were failing dismally to fill skills gaps across the economy, leaving many visa holders exploited, working menial jobs, or unemployed:

Out of the 1156 international graduates from 35 Australian universities in our survey, 76% said access to the visa was an important factor in their decision to study in Australia…

However, a range of systemic issues persist…

Our survey found that more than half were unemployed or working outside their field of study, in lower skilled areas like retail and hospitality…

Our research shows that many international graduates become disillusioned because they were given the impression, mostly from offshore education agents, that the 485 visa is a guaranteed pathway to permanent residency or employment.

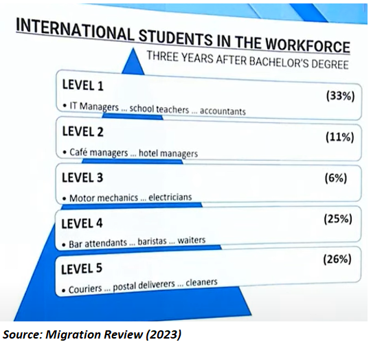

Labor’s Migration Review also showed that more than half (51%) of international student graduates with bachelor’s degrees were working in low-skilled jobs three years after graduation:

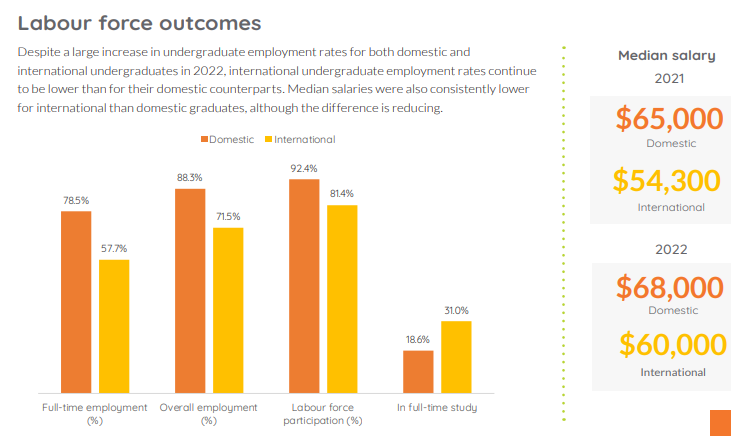

The Graduate Outcomes Survey (GOS) also consistently shows that international graduate employment rates, participation rates, and median salaries are well below those of domestic graduates:

Source: Graduate Outcomes Survey (2022)

It is a sad indictment of the international education system that it produces so many graduates working in low-skilled and low-paid jobs. It is also one of the drivers of Australia’s low productivity.

Australia must instead target a smaller intake of higher-quality international students by:

- Raising entry standards (i.e., English-language proficiency and entrance exams before being offered a place);

- Raising financial requirements, with funds deposited in an escrow account for use while studying in Australia; and

- Removing the explicit link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

The above reforms would lift student quality, raise export revenues per student, and lower enrolment numbers to sensible and sustainable levels that align with international norms.

These reforms would also help improve teaching standards and the experience for domestic students, which should be our universities’ top priority.

Student visas must not be perceived as de facto work visas and tickets for permanent residency.

It was a mistake for the Knight Review to include immigration and work rights in the international education compact.

The federal government needs to unwind the prior decade’s foolishness.