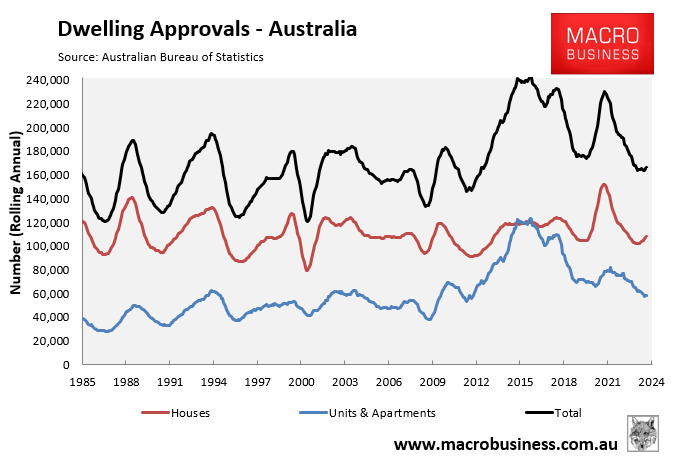

Last week, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) released dwelling approval data, which revealed that only 166,200 dwellings were approved in the year to August, which is 73,800 (31%) below the 240,000 annual run rate required to meet Labor’s 1.2 million housing target.

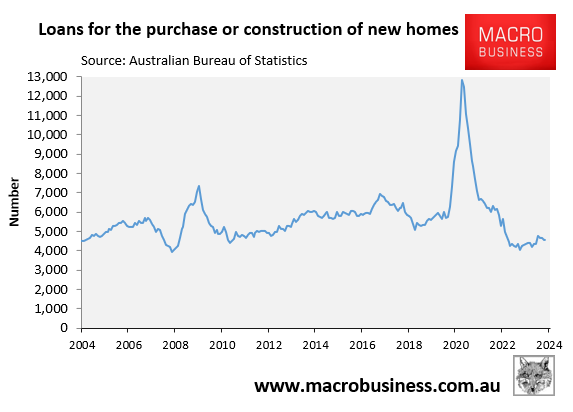

On Friday, the ABS also released data on the number of loans issued for constructing or purchasing new dwellings.

As illustrated in the following chart, there were only 4551 loans for newly constructed homes issued in August, which was 65% below the early 2021 peak:

Tim Reardon, the chief economist at the Housing Industry Association, noted that “lending for new home purchase and construction remained about the lowest levels since 2002”.

The poor result is obviously another blow to the Albanese government’s target to build 1.2 million homes over five years.

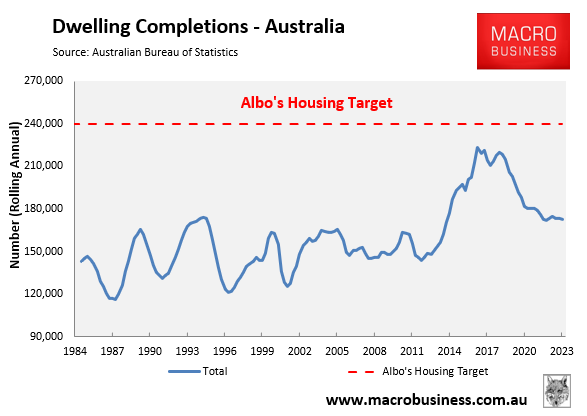

I have argued repeatedly that the government’s housing target is delusional for a number of reasons.

First, Australia has never built more than 223,500 dwellings in a 12-month period. Therefore, achieving 240,000 homes for five straight years is highly improbable even under ideal macroeconomic conditions.

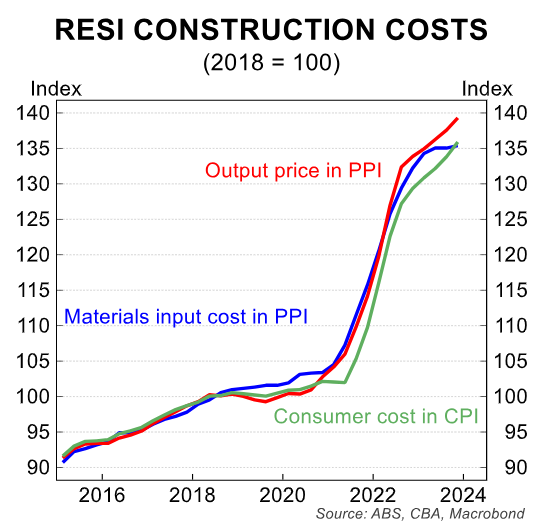

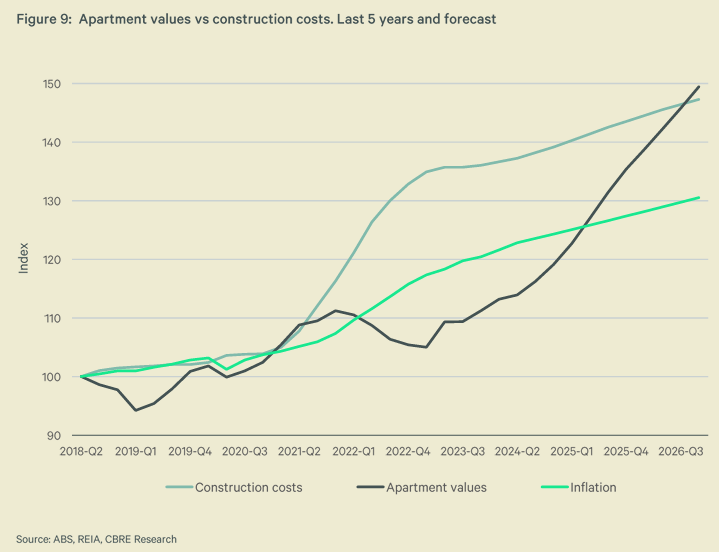

Worse, macroeconomic conditions are far from ideal. Construction costs have risen by around 40% since the beginning of the pandemic:

The official cash rate (4.35%) is far higher today than it was when construction levels peaked in 2017 (1.5%).

Homebuilders are competing for labour against government ‘Big Build’ infrastructure projects.

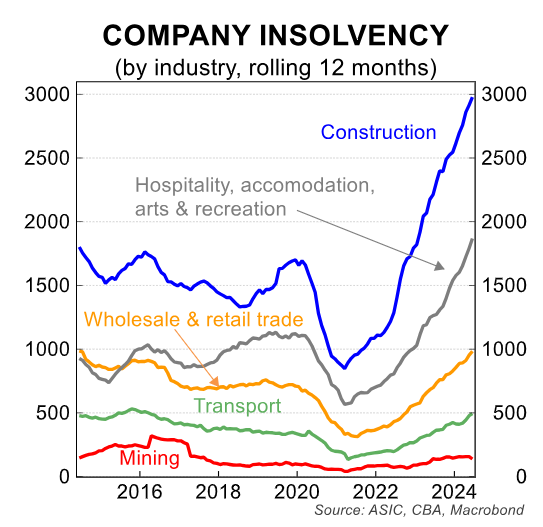

Swathes of homebuilders have collapsed amid high costs and falling productivity:

Indeed, Sameer Chopra, the head of research in the Pacific for the world’s largest commercial real estate group, CBRE, last month argued that the “volume of supply is unlikely to be turned on” until prices rise to match the surge in construction costs.

CBRE notes that “in the last five years, values have not kept pace with construction costs”, as illustrated below.

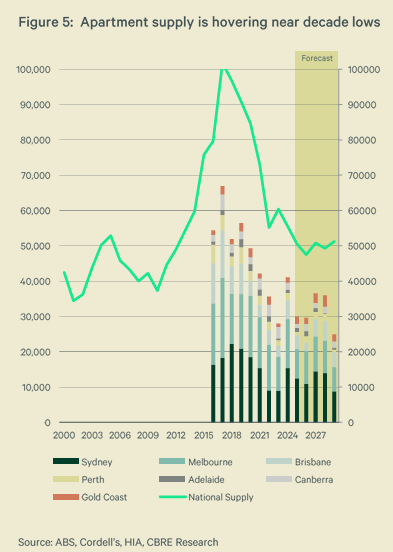

As a result, CBRE forecasts that apartment supply will only average around 50,000 annually between 2025 and 2029, which is around half the 2017 peak and well below the rate required given population growth.

In short, those hoping that more “supply” will magically improve housing affordability are deluding themselves, given that build costs are structurally higher.

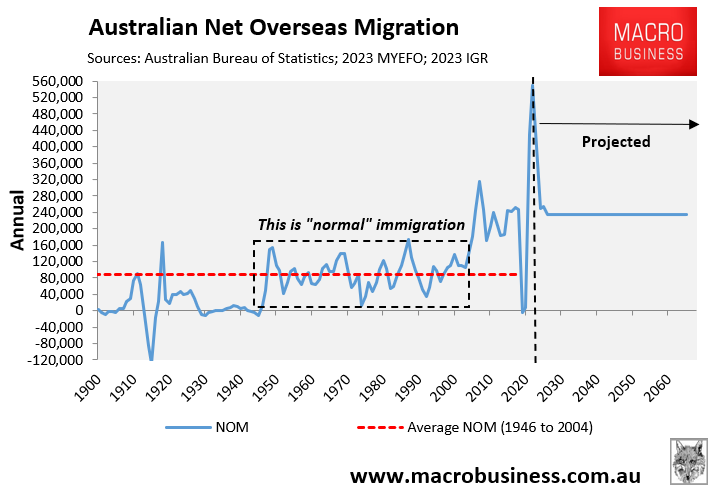

The number one solution to Australia’s housing crisis is to significantly cut net overseas migration to a level that is below the nation’s capacity to build housing and infrastructure.

Sadly, the federal government has targeted high levels of net overseas migration forever, which means that Australia’s housing crisis will become permanent.