The RBA is still going to cut in December.

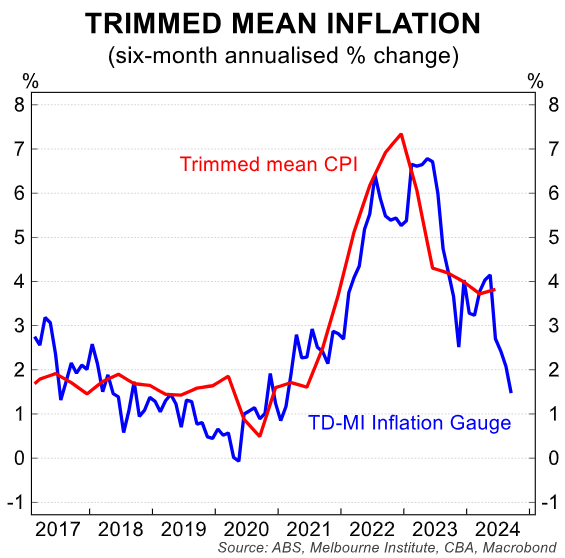

The reason is inflation will be too weak if it does not, Especially so after another round of energy bill rebates is announced:

Gareth Aird at CBA:

Hiring continues to grow at a strong pace, albeit most of the jobs growth has come in the non‑market sector over the past year. And there is not yet evidence that the weakness in private demand growth has spilled over to job losses in any discernible way.

Overall, the recent labour market data does not strengthen the case for the RBA to commence normalising the cash rate this calendar year. Indeed at the margin it weakens it. That means the conviction we have in our call for a 25bp December cut to the cash rate has dipped today. But while the risk has firmly shifted to a later start date for the first reduction in the cash rate, we stick with our call.

The RBA has the dual mandate of price stability, as defined by the 2‑3% inflation target, and full employment. There is no numerical target around what constitutes full employment. Instead full employment is the current maximum level of employment that is consistent with low and stable inflation.

The RBA’s point estimate of the non‑accelerating inflation rate of unemployment (NAIRU) is 4.3% (i.e. 0.2ppts above the current unemployment rate). But there is a lot of uncertainty around this estimate.

Pre‑pandemic the unemployment rate at ~5¼% was too high. Wages growth was too weak and inflation was below target. But the cyclical trough in the unemployment rate post‑pandemic of 3.5% was too low to be consistent with the inflation target.

The massive fiscal and monetary policy stimulus injected into the economy due to the negative shock of the pandemic meant the economy roared back to life and the unemployment dropped like a stone to 3.5%.

The speed at which this occurred meant there was no time to gather evidence and ‘test’ where the NAIRU might be. As such, estimates of the current NAIRU are still clouded in a lot of uncertainty (see facing chart for a version of the Philips Curve since inflation targeting started in 1993).

Given this uncertainty, the RBA will be looking to the inflation and wages data to guide where full employment might conceivably sit. This process is somewhat of an experiment that is being conducted in real‑time. As such, it makes the job for policymakers a little more complicated than usual.

Very good. The RBA has no clue where NAIRU is. The reason is the economy is never the same.

- Pre-pandemic, we had an income-starved economy with a perpetual supply-side labour market shock.

- During COVID, we had a tearaway private sector economy juiced by massive monetary and fiscal stimulus cut off from global labour supply.

- Post-pandemic, we have a moribund private sector economy crowded out by public spending on low-rent health care and the return of a permanent labour supply shock.

Is three any more wage growth positive than one? Pfft. If so, it’s not by much.

Even under the conditions of two, wages barely flopped over 4% in Australia, far below the inflation rate.

Australia’s NAIRU is far lower 4.3% today and could probably go back to 3.5% and lower if all the jobs are going to cheap migrants, which they are.

Australians lost about 100k jobs in the last year.

Worrying about wage growth in Australia is like worrying about being impaled by a runaway unicorn.

The RBA will cut as inflation disappears.