The housing industry and YIMBYs argue that Australia’s shortage of housing could be solved by rezoning our cities for greater densities, thereby allowing apartments to be built in the ‘missing middle’ of our cities.

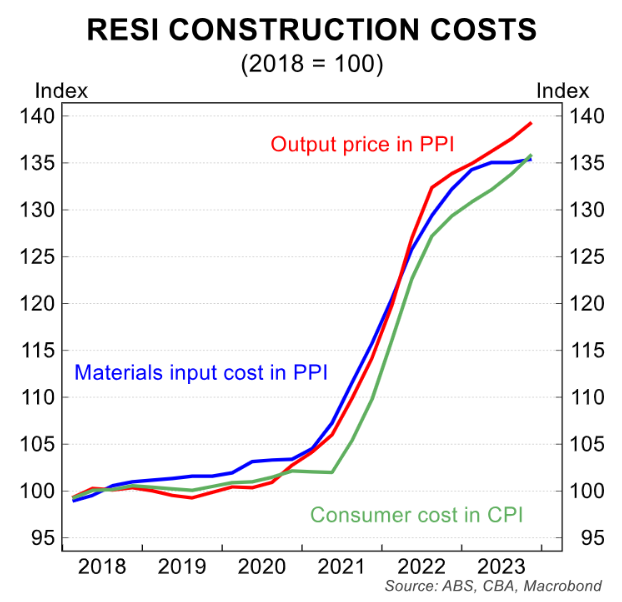

However, their simplistic claims ignore the fact that construction costs have soared by around 40% since the beginning of the pandemic:

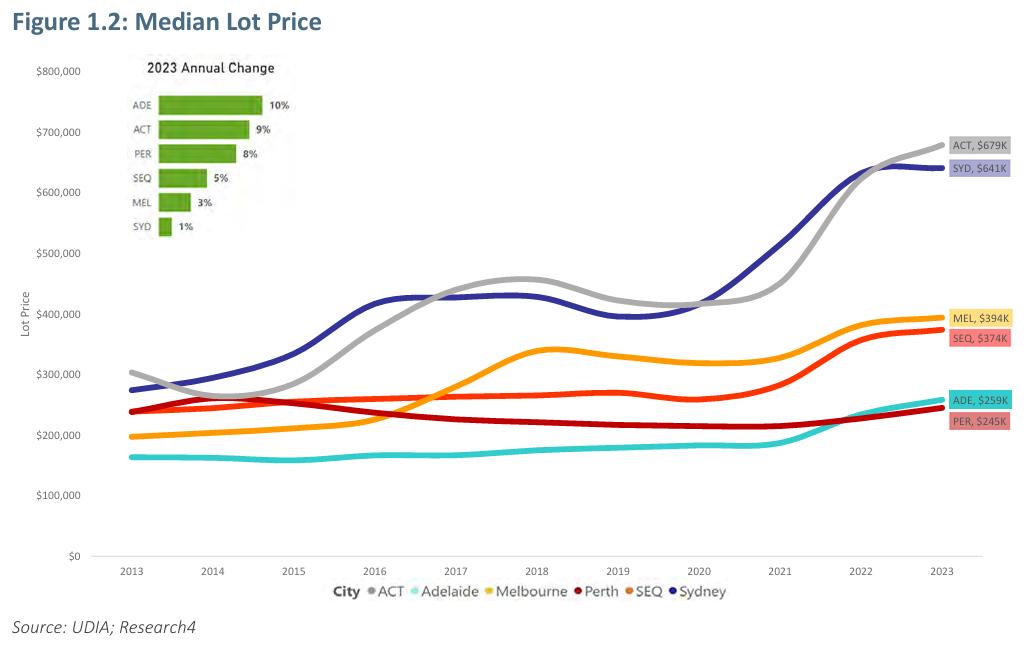

Lot prices have also risen across our capital cities:

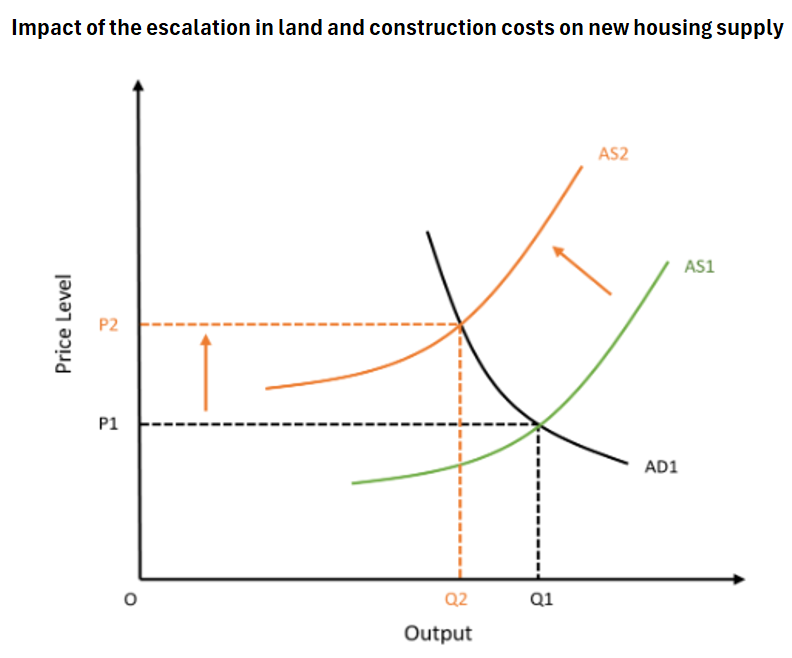

Together, these factors have made it far more expensive to build a home and have effectively shifted the housing supply curve left, meaning that fewer homes can be built at given price points:

Thousands of construction firms have also folded since the beginning of the pandemic, which has reduced capacity in the homebuilding industry.

Builders are also competing for workers against government infrastructure projects, which has further reduced capacity.

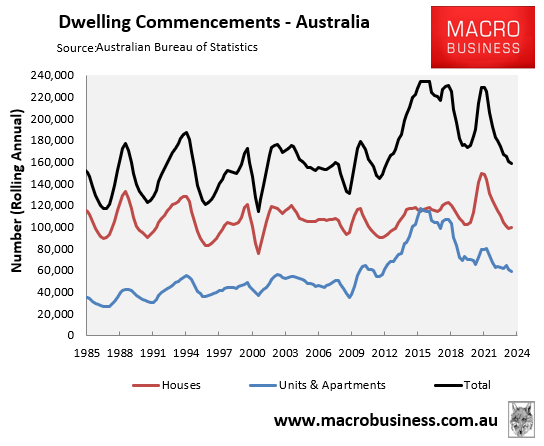

For the above reasons, dwelling commencements have collapsed to an eleven year low, tracking one-third below the Albanese government’s housing target:

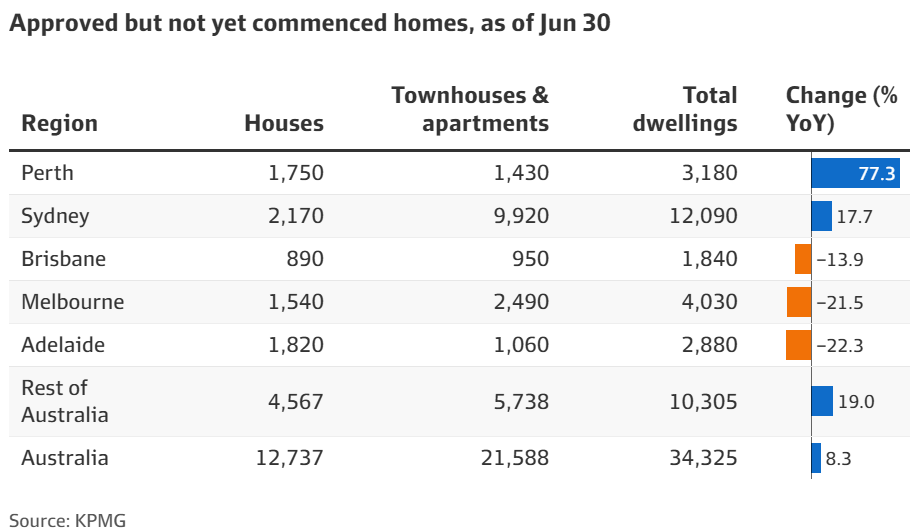

KPMG has reported that there were just over 12,000 dwellings approved but not commenced in Sydney over the year to June, representing an increase of 18%.

The stalled dwellings would be able to house around 30,000 people, based on the average size of an Australian household being 2.5 people, while Sydney accounts for around 35% of the national total of 34,325 dwellings that are approved but not yet under construction.

According to KPMG, 82% of Sydney dwellings stuck in limbo are apartments and townhouses.

KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley says development conditions in Sydney are “very tough”.

“The construction sector crunch in NSW has been more acute than any other state, driven largely by construction cost increases and rising interest rates”, he said.

This follows Rawnsley’s comments in May explaining how rising construction costs and labour shortages were behind the stalled housing commencements.

“With all the construction price increases and where interest rates have landed, it’s hard for developers to make those more medium to high-density projects stack up”, he said.

“Sometimes people also forget that interest rates also impact on the developer side as well – it means they can’t borrow as much to get the projects up and running”.

More than 1400 building companies have gone bust in NSW alone since 2021-22. Those insolvencies have further reduced the supply of labour for residential construction.

Sydney developer Mark Bainey said many developers were finding it hard to secure builders and tradies to complete projects.

“I don’t see things improving much in the near term”, he said.

Apartment developer Tim Gurner has also admitted that easing planning rules wouldn’t materially boost housing construction due to supply constraints:

[Gurner] estimated that less than half of the 51,000 new dwellings approved in Victoria last year would actually get built, due to poor pre-sales, financing or developer capability.

The Municipal Association of Victoria says that, as of September, 120,000 houses, townhouses and units had been approved with construction yet to begin, with councils using this to hit back at claims they are to blame for the housing bottleneck.

Clearly, the housing industry and YIMBY approach of rezoning our cities for high density will not solve Australia’s housing supply problem. Costs are simply too high and there is a shortage of labour and capacity across the industry.

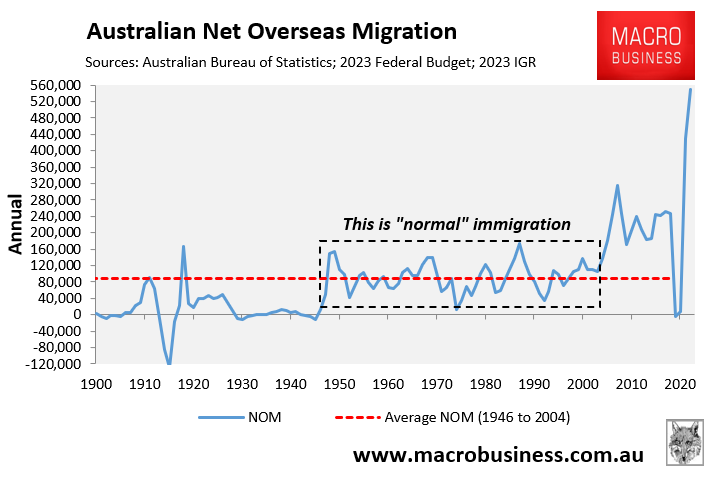

A cheaper, easier, and faster solution to the supply problem is to limit net overseas migration to a level below the country’s capacity to create housing and infrastructure.

Otherwise, due to rapid population growth, housing demand will always exceed supply.