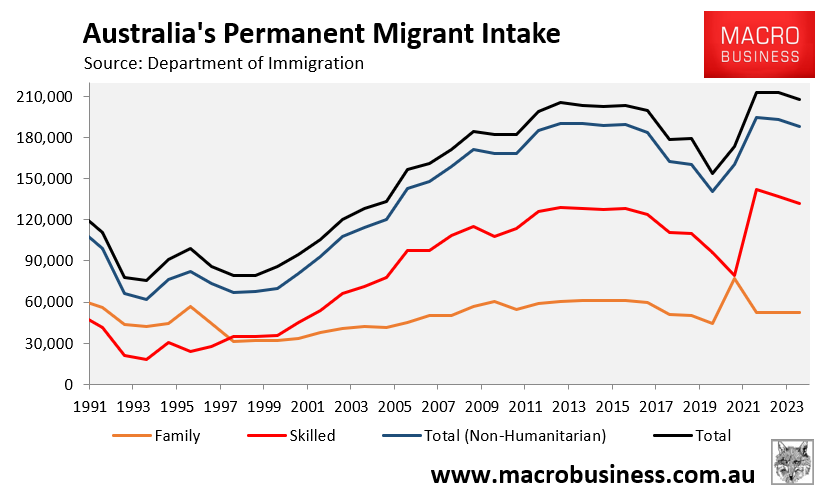

Australia has a very large skilled migration program.

Over the last 20 years, Australia has granted 2.3 million permanent skilled visas.

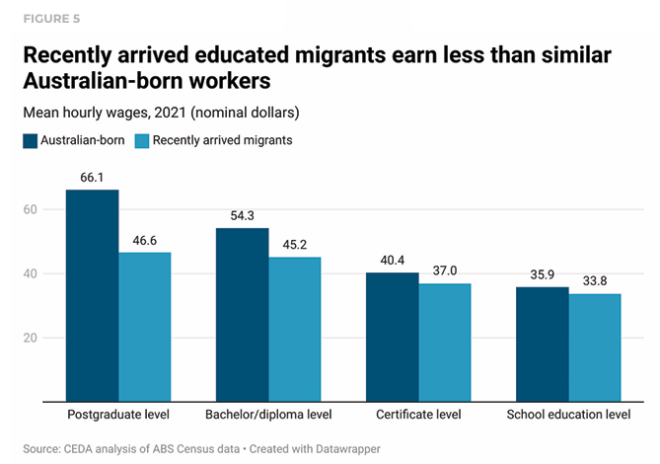

Earlier this year, the Committee for Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) published research revealing that half of skilled migrants work in occupations that are below their qualifications and earn significantly less than Australians with the same skills.

Even if they have identical qualifications, migrants who have been in the nation for 2-6 years earn at least 10% less than Australian-born citizens (see chart below).

CEDA stated that it could take up to 15 years for their incomes to catch up to locals.

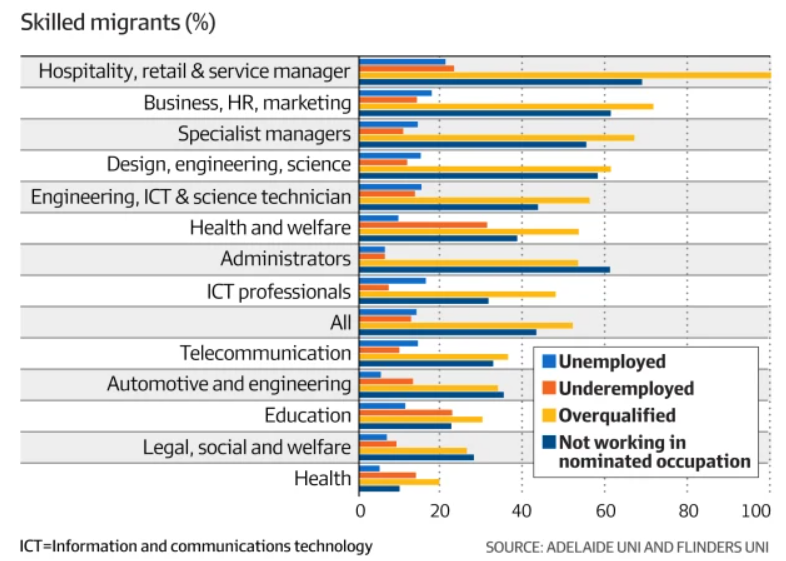

According to research from Adelaide University’s George Tan, 43% of skilled migrants who used the state-government-sponsored visa system were not engaged in their nominated occupation.

Furthermore, the vast majority of skilled migrants working as retail, hospitality, and service managers were overqualified for their positions.

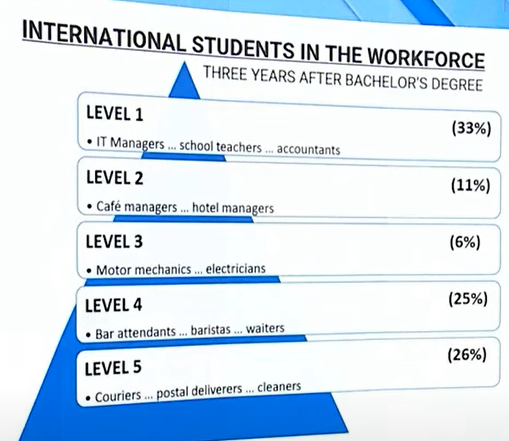

Meanwhile, the Migration Review uncovered that 51% of overseas born university graduates with bachelor’s degrees were employed in unskilled jobs three years after graduation:

Source: Migration Review (2023)

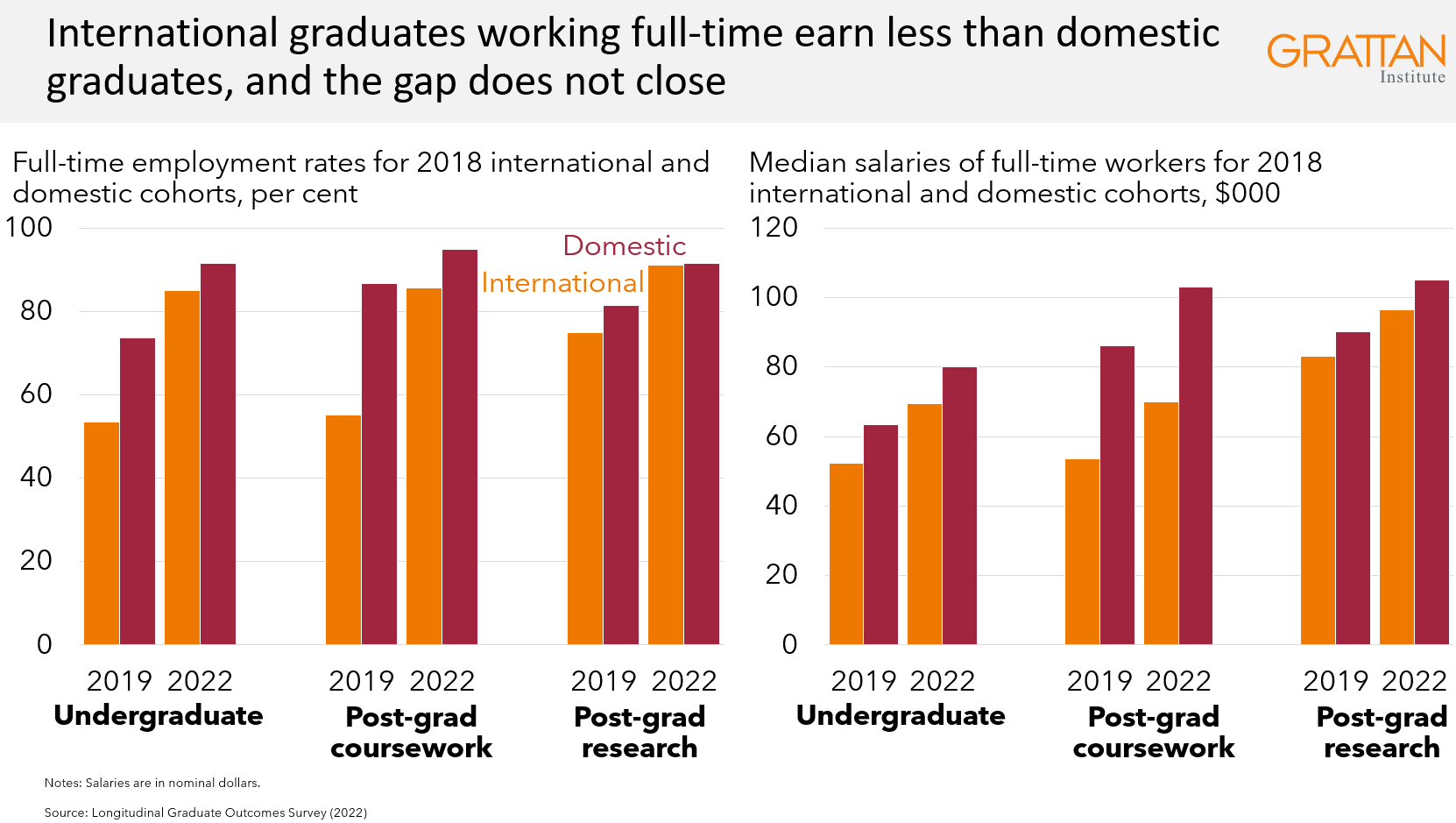

The Graduate Outcome Survey also discovered that student graduates earn much less than local-born graduates and have poorer labour market outcomes:

Activate Australia’s Skills, a partnership of over 50 industry groups and unions, released research this month that revealed 621,000 permanent skilled migrants (44%) are working below their skill level. This is despite the fact that two-thirds of the migrants came through the government’s skilled migration program.

The group urged the federal government to take over skills recognition processes from professional bodies and to introduce a loan program similar to HECS/HELP to assist migrants in meeting “cost prohibitive” training and registration criteria.

“We get … engineers and doctors who are driving rideshare or stacking shelves”, Chief executive of Settlement Services Australia, Violet Roumeliotis said.

“We have qualified nurses who worked for many years in other countries here in Australia, but they’re cleaning, they’re working in retail or hospitality”.

“It’s quite an extraordinary situation”.

Last week, the Guardian’s Greg Jericho released research showing that “we still have very high skills shortages” despite record levels of migration.

“Across the 916 occupations surveyed, 33% of all occupations had skill shortages at the national level… that’s still higher than in 2021 and 2022, and the levels are much higher for jobs needing specific skills”.

“Just over 39% of jobs with “skill level 1” (which requires a bachelor degree or higher) have skills shortages, while jobs with a “skill level 3” (which requires a trade certificate with at least two years of on-the-job training) are very much in need of workers”, noted Jericho.

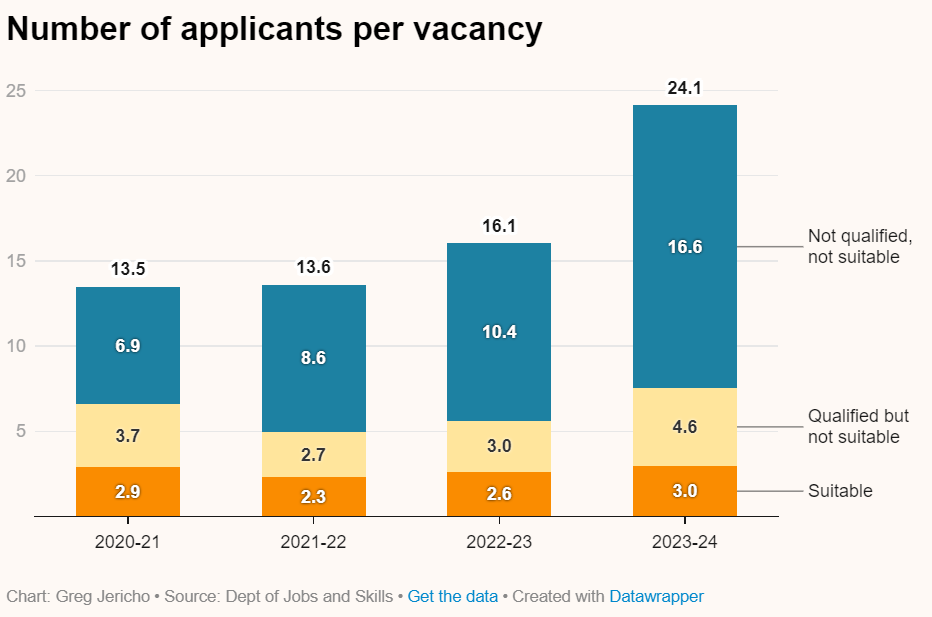

However, Jericho showed that the shortages are not because of a lack of applicants, which have swelled. “There are a lot more people applying for each job”.

Rather, it is because there is a lack of “qualified and suitable candidates applying for jobs”:

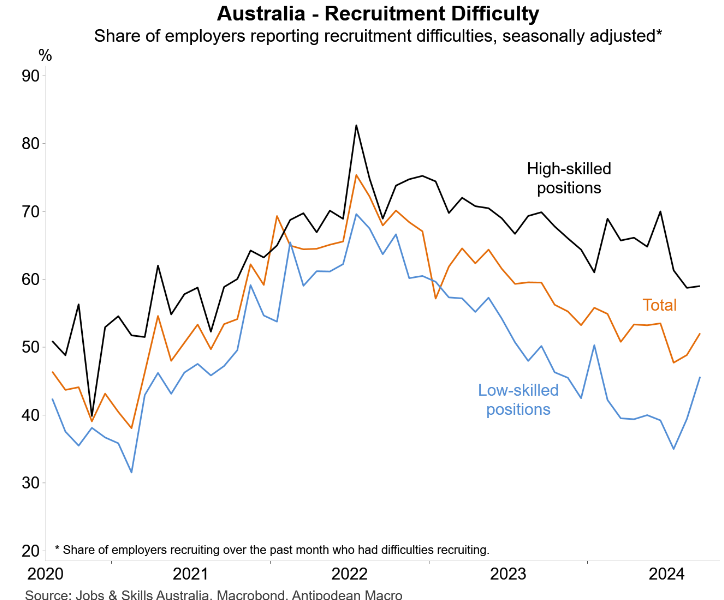

The following chart from Justin Fabo at Antipodean Macro tells a similar story. It shows that Australia is suffering from a chronic shortage of highly-skilled workers but is oversupplied with lower-skilled workers:

All Australians should ask why we are running such a large immigration program when most of the migrants that we import are working in unskilled roles unrelated to their area of qualification?

Surely the best approach is to make all skilled visas employer-sponsored, so that qualified migrants can begin working in their field of expertise as soon as they arrive?

Australia should also increase the minimum salary applying to all skilled visas above the median full-time wage (currently ~$90,000).

The fact that Australia’s population has increased by 8.4 million people (45%) this century alone, but skills shortages are worse than ever, highlights the fatal flaws in Australia’s purportedly ‘skilled’ migration system.

The current system is actually creating skills shortages by supplying the economy with the wrong types of workers, while also exacerbating housing and infrastructure shortages.

Australia, therefore, requires an immigration system that is significantly smaller in size and focused on the skills we actually need.