Over the weekend, Victorian Premier Jacinta Allan chose the wealthy suburb of Brighton to launch her plan of seizing planning controls away from local councils to create 50 activity centres the government has earmarked for higher density.

These areas will be rezoned for high-rise apartment complexes of 10 to 20 storeys near train and tram stations, alongside “gentler, scaled” height limits within 800 metres of train stations.

These activity areas also include other wealthy areas, such as Armadale, Glenferrie, Glen Iris, Malvern, and Toorak.

Allan is attempting to frame herself as the champion for young people, with the opposition and nimbys painted as the villains.

It is all part of Labor’s target of building 800,000 homes over a decade—a level of construction that has never been built before—and 2 million new homes by 2051.

The reality of the situation is that just because the Victorian government has rezoned these areas for high-rise does not mean that more homes will be built. Nor will it make housing more affordable.

As reported by The Age, “developers will be forced to pay a new charge to fund schools, parks and public transport with the state government set to trial the fee in the first 10 of its so-called activity centres, as it considers a universal model for all areas where new housing is built”.

Will a high-rise future deliver affordable housing to the residents of Melbourne? Absolutely not. They haven’t done so over the past 20 years.

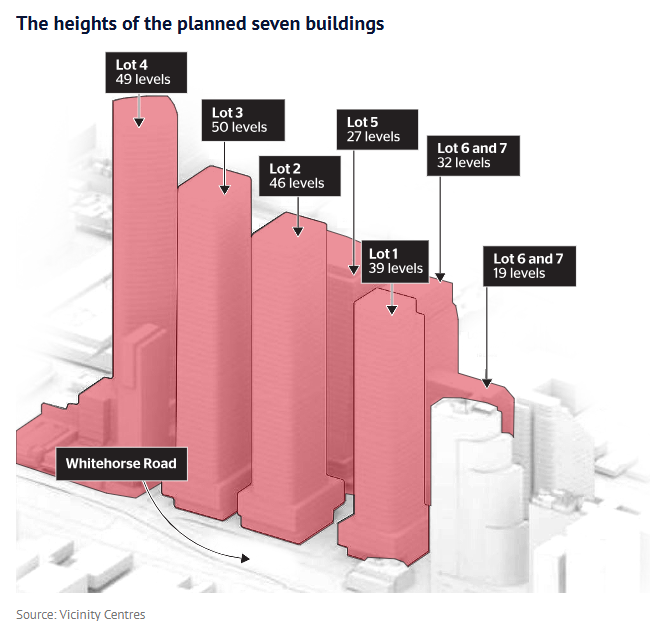

The absurdity of the situation was illustrated this year when The Age reported that “the Planning Minister, Sonya Kilkenny, had approved the $1.57 billion Vicinity Centres project – which will change the shape of Box Hill with towers up to 50 storeys and a total of 1700 apartments”.

So, that is $1.57 billion to build 1,700 apartments, which equates to $923,529 per apartment. In what world is that affordable?

To add insult to injury, housing experts warned that these new apartment complexes will not be viable unless there is a substantial rise in the average price of apartments.

Property industry analysts Charter Keck Cramer argue that apartment prices will need to rise by at least 15% to encourage developers to build new high-density homes.

However, this will price apartments above what many buyers are willing or able to afford.

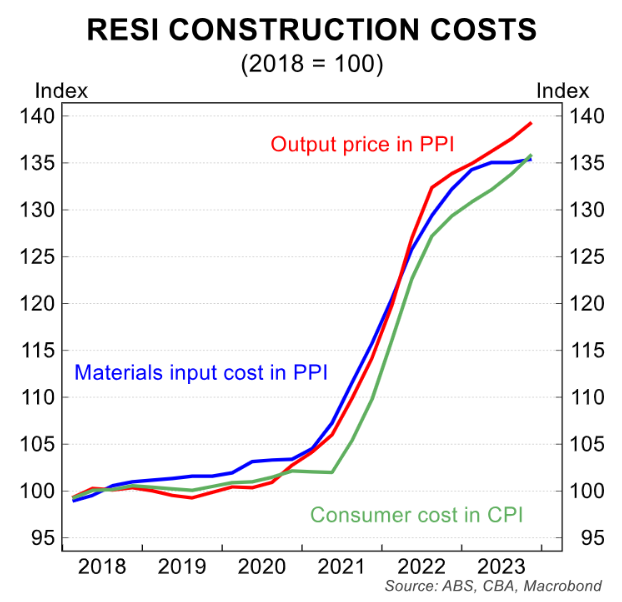

“Because building costs have jumped by 30% to 40%, prices have to basically go up to be about 30% higher compared to pre-pandemic levels”, Charter Keck Cramer national executive director of research Richard Temlett said.

“And what that means is that even with these incentives in place, there’s certain projects that will still not be financially viable”.

“The prices of established units need to recalibrate upwards by around 15% for new stock to be accepted by the market at current price points”, said its report, describing the price discrepancy between new and established apartments as a “major handbrake” for delivering new homes.

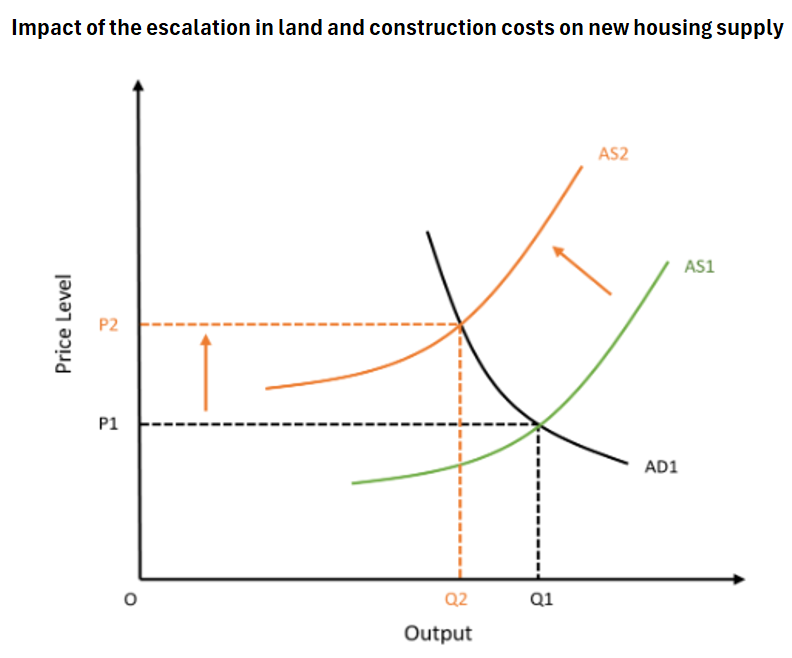

As I noted on Tuesday, the escalation of costs and labour shortages, not planning, are the major impediments to delivering more housing.

These supply shocks have effectively shifted the housing supply curve to the left, making it more expensive to build homes at each price point and reducing overall construction capacity:

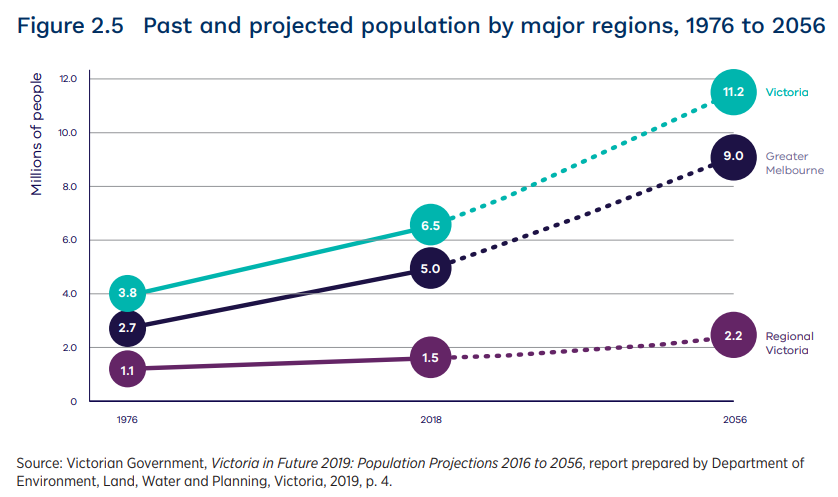

The inconvenient truth about Victoria’s housing situation is that the government is desperately trying to create supply in a bid to keep up with the state’s extreme immigration-driven population growth.

Melbourne’s population has grown like an out-of-control science experiment this century, from 3.5 million at the turn of the century to around 5.4 million people currently.

Melbourne’s population is officially projected to grow by another 3.6 million people over the next 32 years—i.e., by more than the city’s entire population in 2000.

Such an extreme increase in population will inevitably transform Melbourne into a crowded high-rise city.

Is that what Melburnians want?

Victoria’s housing policy debate should really be a debate about immigration levels.