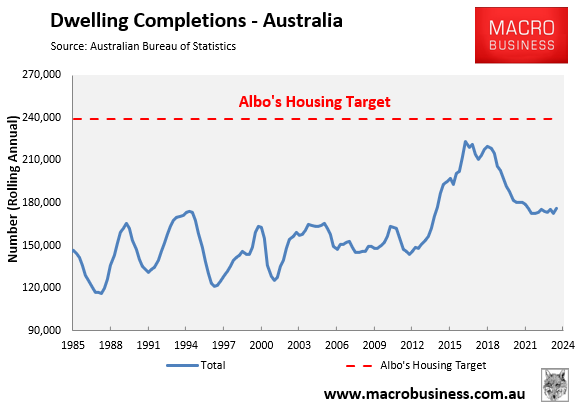

The Albanese government’s target to build 1.2 million homes over five years has gotten off to a rocky start, with construction rates behind by around one-third.

To meet its target, the government needs high-rise construction to accelerate.

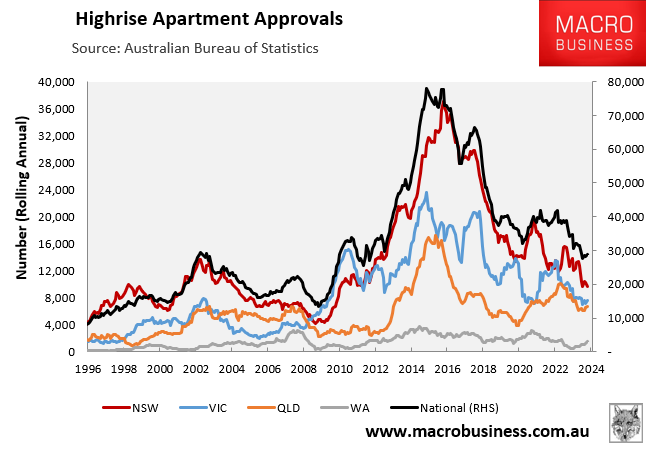

The governments of Australia’s two largest states, New South Wales and Victoria, have undertaken zoning reforms to facilitate the construction of high-rise apartments in established inner and middle-ring suburbs.

However, as shown in the following chart, approvals for high-rise apartments have collapsed across Australia:

Nationally, annual high-rise approvals are tracking 63% below their peak, with New South Wales (-74%) and Victoria (-68%) tracking even further behind.

A new report from the Property Council warns that building high-rise apartments is no longer financially viable.

The cost of delivering an apartment was generally higher than the market was willing to pay; therefore, projects do not stack up.

The report blamed rising construction costs alongside labour shortages, driven in part by competition from government projects.

“Contrary to the common rhetoric, margins are not driven by ‘greed’; there are minimum thresholds necessary for securing project finance and managing risks”, the report said.

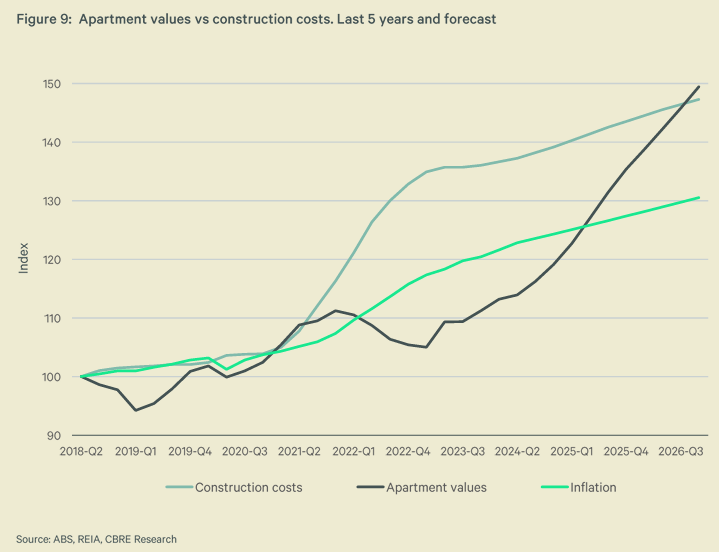

“Anecdotally, developers report that construction estimates are now almost double the cost of similar developments five years ago”.

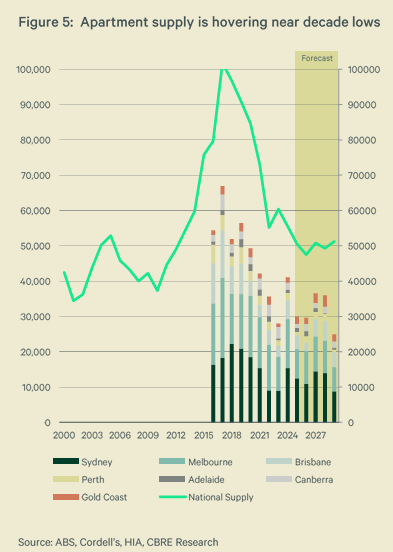

Similar sentiments were expressed by CBRE, which projected that only 50,000 units would be constructed annually between 2025 and 2029, which is around half the level of last decade’s peak.

CBRE also said that apartment prices needed to rise significantly to make construction feasible for developers.

“That disparity [between prices and costs] is currently at 23%”, said Sameer Chopra from CBRE. “We expect this gap to close out and revert to a premium”.

Charter Keck Cramer also warned that new and established apartment prices needed to rise significantly to make development feasible, but that it could choke off buyer demand.

“Because building costs have jumped by 30% to 40%, prices have to basically go up to be about 30% higher compared to pre-pandemic levels”, Charter Keck Cramer national executive director of research Richard Temlett said.

“The prices of established units need to recalibrate upwards by around 15% for new stock to be accepted by the market at current price points”.

Meanwhile, Sydney developer Luke Berry warned that the shortage of apartment supply would worsen “because it’s very hard to make them stack up due to high costs”. As a result, prices will will shoot higher.

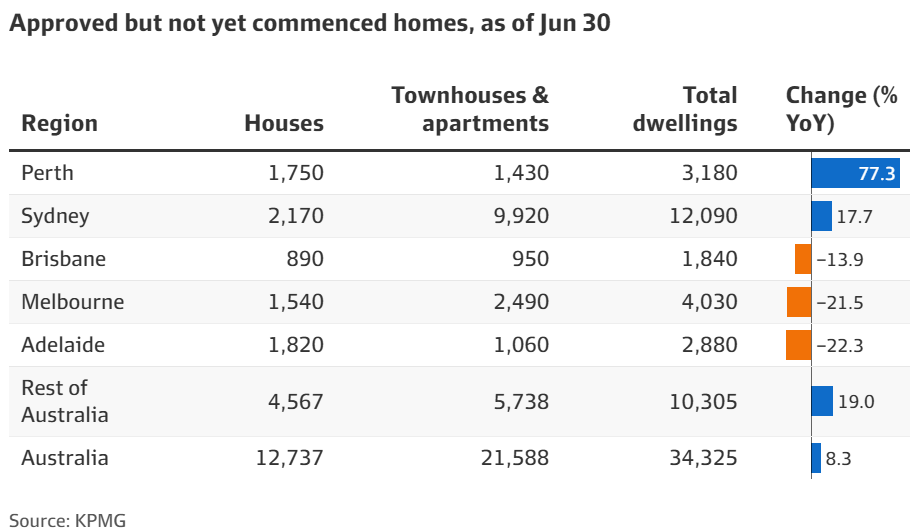

According to a recent KPMG report, more than 30,000 dwellings have been approved for construction but have yet to be started, with most being apartments and townhouses.

The building climate is unlikely to improve anytime soon, given that:

- Interest rates are expected to remain structurally high for an extended period.

- Construction expenses are around 40% higher today than before the pandemic.

- Thousands of home builders have gone bust.

- Builders are competing with government ‘big build’ infrastructure projects for labour and resources.

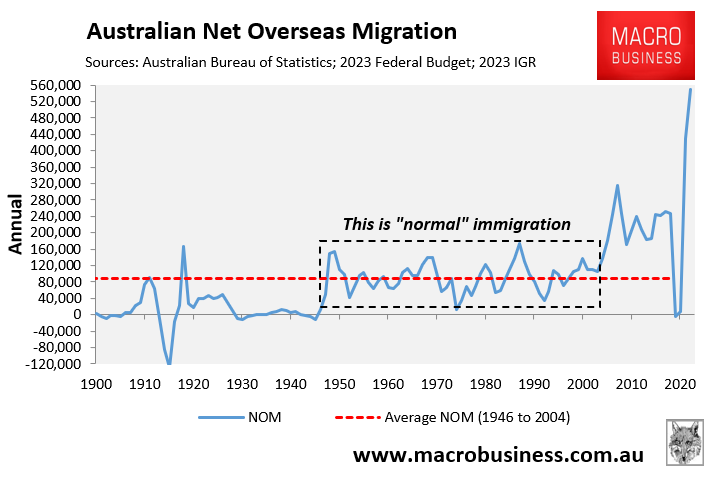

With the supply side of the housing market likely to remain stunted for the foreseeable future, the federal government needs to slow demand by cutting back hard on immigration.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing crisis will deteriorate further.