Australia’s governments want to ‘solve’ the housing crisis by pushing Australians into high-rise apartments.

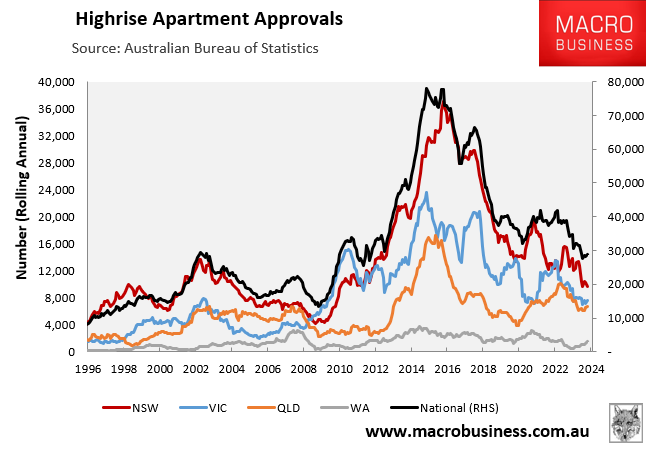

However, high-rise apartment approvals have collapsed, as illustrated in the following chart:

Since peaking between 2015 and 2017, high-rise approvals have fallen by the following amounts across the major markets:

- NSW: down 74% from the September 2016 peak.

- VIC: down 68% from the October 2015 peak.

- QLD: down 60% from the April 2016 peak.

- Australia: down 63% from the October 2015 peak.

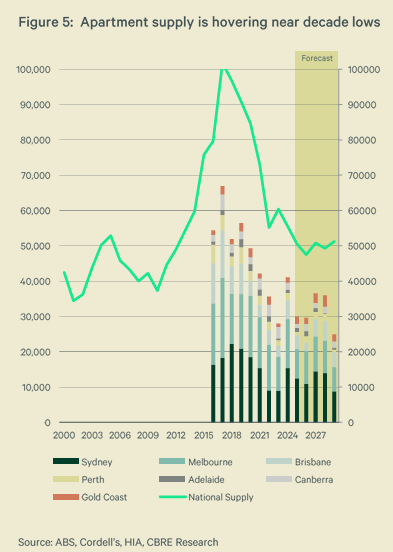

Last month, CBRE forecast that overall Australian apartment supply would average only around 50,000 units annually between 2025 and 2029. This would be around half the level of the 2017 peak and well below the rate of supply needed given projected population growth.

Given the high cost of renting, many consumers would like to purchase a moderately priced apartment. However, developers state that increased costs and longer development times make it difficult to build them, and that only the most lucrative higher-end projects are feasible at the present time.

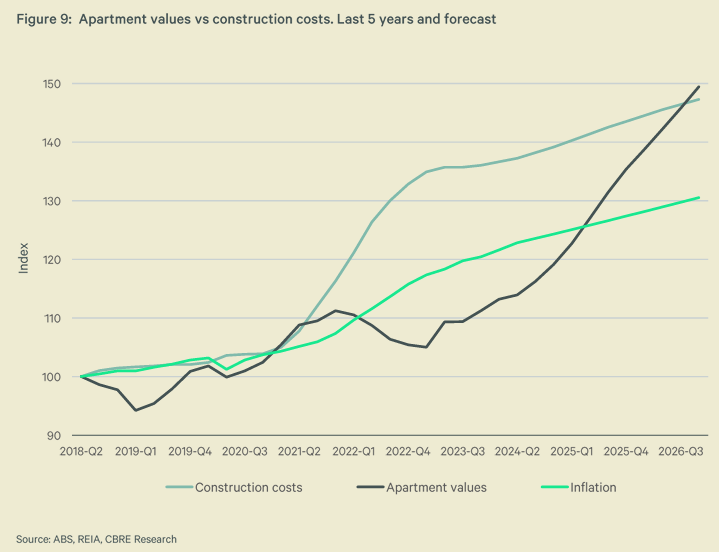

CBRE warned that apartment values had failed to keep pace with construction costs over the past five years, and that prices would need to rise significantly to make construction feasible.

“That disparity [between prices and costs] is currently at 23%”, said Sameer Chopra from CBRE. “We expect this gap to close out and revert to a premium”.

“In our view, apartment values will need to accelerate significantly higher to entice developers”, he said.

Charter Keck Cramer also said that apartment prices for new and established stock needed to rise, which would choke out many prospective buyers.

“Because building costs have jumped by 30% to 40%, prices have to basically go up to be about 30% higher compared to pre-pandemic levels”, Charter Keck Cramer national executive director of research Richard Temlett said.

“The prices of established units need to recalibrate upwards by around 15% for new stock to be accepted by the market at current price points”.

Lendlease’s Tony Lombardo also told last week’s Australian Financial Review housing roundtable that the cost of building a high-rise apartment block has surged by 25% to 30% since the pandemic.

New figures from the Master Builders Association show that it took 18.5 months in 2011 on average for a new apartment project to go from approval to completion, but that figure rose to 33.3 months last year.

“There is a range of contributing factors, including labour shortages, declining productivity, union pattern agreements, supply chain disruptions, complex regulatory requirements, occupational certificate backlogs and critical infrastructure delays”, MBA chief executive Denita Wawn said.

“As a result, we’ve seen productivity decline by 18% over the last decade”.

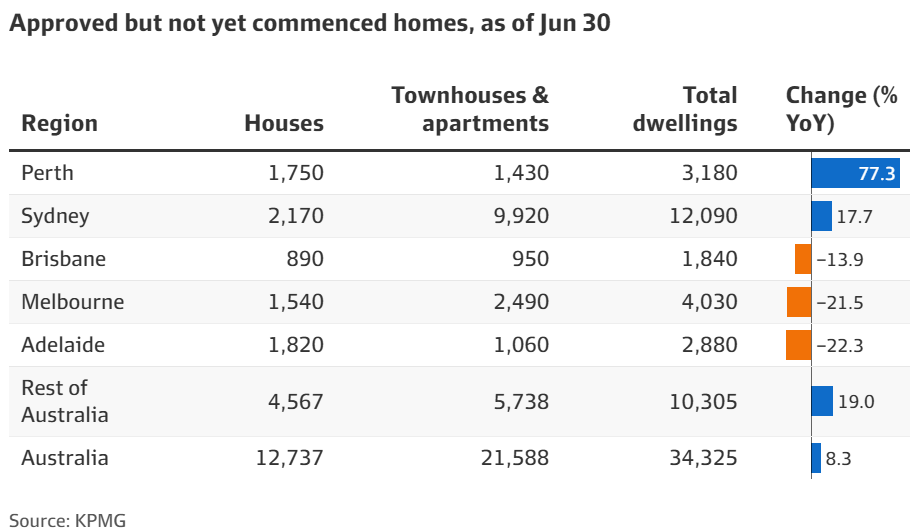

Meanwhile, KPMG reported last month that about 30,000 new homes have been approved but not started, with over 80% in Sydney being apartments and townhouses.

These dwellings usually take longer to build than detached houses, as they need sufficient presales to get going in the first place and need larger and more skilled workforces to deliver.

“With all the construction price increases and where interest rates have landed, it’s hard for developers to make those more medium to high-density projects stack up”, KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley explained in May.

“Sometimes people also forget that interest rates also impact on the developer side as well – it means they can’t borrow as much to get the projects up and running”.

Apartment developer Tim Gurner also recently admitted that easing planning rules wouldn’t materially lift housing construction due to capacity constraints:

[Gurner] estimated that less than half of the 51,000 new dwellings approved in Victoria last year would actually get built, due to poor pre-sales, financing or developer capability.

The Municipal Association of Victoria says that, as of September, 120,000 houses, townhouses and units had been approved with construction yet to begin, with councils using this to hit back at claims they are to blame for the housing bottleneck.

Clearly, the government’s and YIMBYs approach of rezoning our cities for high density will not solve the supply problem. Costs are too high and there is a lack of labour and capacity across the industry.

There are also legitimate concerns surrounding the quality of high-rise construction.

A November 2023 NSW government strata survey found that more than half of newly registered buildings since 2016 had at least one major defect, costing an average of $331,829 per building to fix.

Research by the Strata Community Association NSW revealed that waterproofing was the most common serious defect followed by fire safety.

These issues were captured in the Four Corners Report, “Cracking up”, revealing a systemic failure to regulate and protect the buying public from shonky workmanship.

Construction lawyer Bronwyn Weir warned that accelerating the construction of high-rise apartment complexes would inevitably result in corners being cut and more quality issues.

“On current estimates, 50% of what will be built will have serious defects”, Weir told The AFR in January.

She warned that “thousands and thousands of apartments have serious defects in their buildings”, describing the problem as “enormous”.

“We have what is now, you know, a systemic failure that is quite difficult to unravel”.

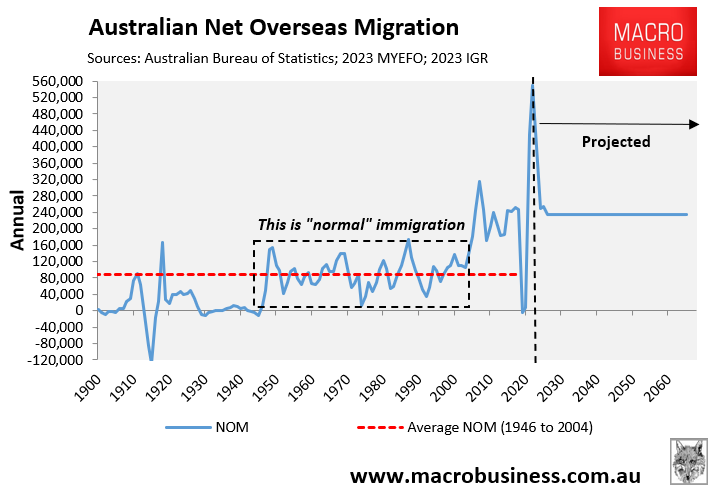

Of course, we would not need to transform our cities into high-rise slums if the federal government did not choose to grow the nation’s population like an out-of-control science experiment via extreme levels of immigration.

The cheapest, easiest, and fastest solution to the nation’s housing supply problem is to limit net overseas migration to a level that is below the nation’s capacity to supply housing and infrastructure.