Australian apartment developments aren’t fit for purpose

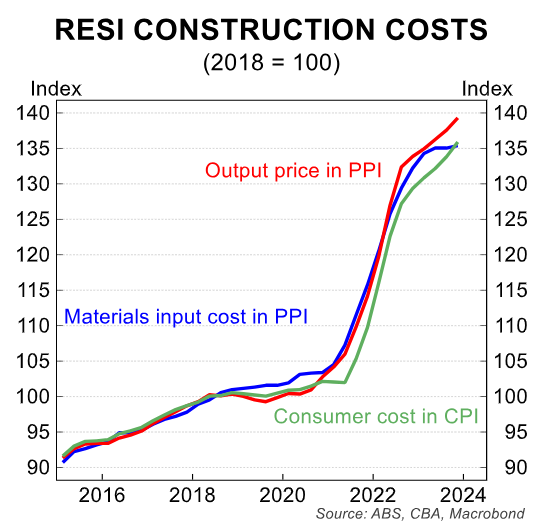

The costs of building housing in Australia have rocketed since the pandemic.

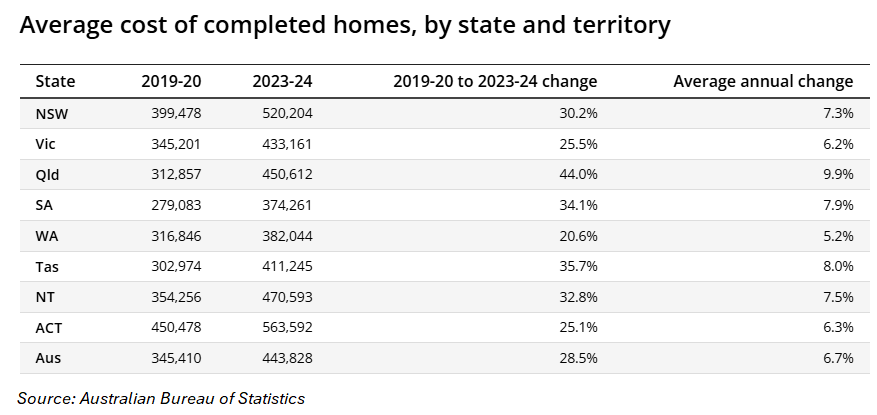

Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data published last week showed that the national average construction cost for homes, including houses, townhouses, and apartments, surged 28.5% from $345,410 to $443,828 between 2019-20 and 2023-24.

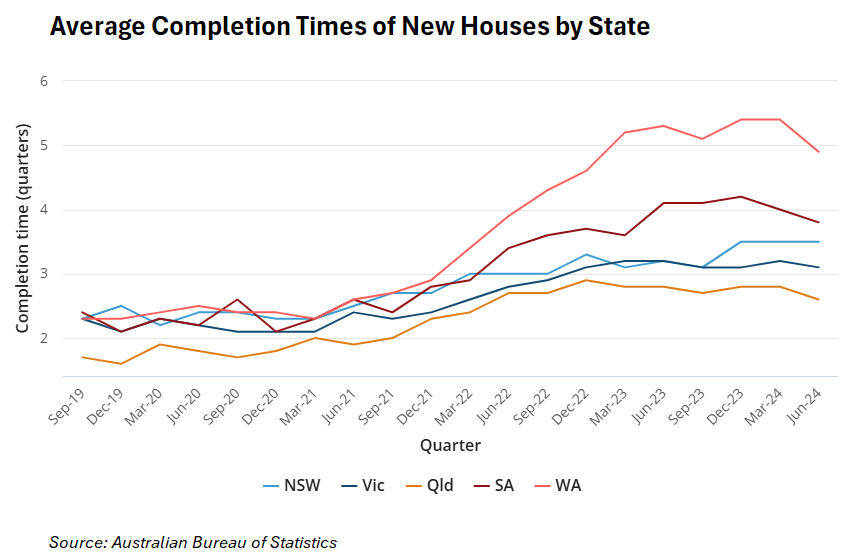

The most significant cost increase has occurred in Queensland (44.0%), increasing from $312,857 in 2019-20 to $450,612 in 2023-24, an average annual growth of 9.9%. However, Queensland homes are completed the fastest, meaning cost increases might have been passed on more quickly.

The smallest increase occurred in Western Australia (20.6%), increasing from $316,846 in 2019-20 to $382,044 in 2023-24, an average annual growth of 5.2%. However, Western Australia also has the longest completion times of all states and territories, which may contribute to a lagged increase in construction costs recorded.

“During the pandemic construction demand increased significantly, coinciding with global supply chain disruptions, rising material and freight costs, and labour shortages. These all contributed to the increased cost to build new homes”, the ABS explained.

However, the ABS notes that the above costs are a lagging indicator and the situation is likely worse now.

“The average cost to build is a lagged indicator of the current construction environment, as it is calculated based on houses which have completed, not those currently under construction”, the ABS noted.

One of the ways that the building industry is mitigating rising costs is by shrinking the size of housing and offering less features.

Indeed, the NSW Productivity and Equality Commission recently recommended building higher towers with smaller apartment sizes, smaller balconies, less storage space, no carparks, and looser rules around natural light as a solution to the housing crisis.

A Deakin University study of 115 two-bedroom apartments for sale in Melbourne found that only 18 were found to be appropriately designed for storing and preparing meals, with some residents forced to store food in bedrooms.

Better Renting executive director Joel Dignam suspected some apartment kitchens were poorly designed because they were built for investors who did not intend to live in the homes.

The NSW and Victorian governments have committed to accelerating the construction of high-rise shoebox apartments in response to the housing crisis.

This has prompted expert warnings that apartment quality will suffer.

“These apartments will be around a long time beyond the current conditions”, Jane Keddie, vice president of the Planning Institute of Australia’s Victorian division, said.

“We’re concerned that there’s a narrative around reducing standards to improve development feasibility”.

“They’re clearly just very, very fixated on housing supply and I think the worry is that we’re making very quick decisions that will have very permanent effects on our city”, Urban Design Forum’s Andy Fergus said.

“Taller buildings need wider streets, more public space, larger lots”.

“I have concerns about the heights being proposed in combination with the lack of a comprehensive urban design process”, SGS Economics and Planning senior associate Andrew Spencer said.

Building construction lawyer Bronwyn Weir also warned that accelerating apartment construction to meet government housing targets will inevitably result in corners being cut, poorer quality, and defects.

“On current estimates, 50% of what will be built will have serious defects”, she said.

Torrens University academics also warned that “as the Albanese government fast-tracks its five-year plan to build 1.2 million dwellings”, the serious defects in apartment buildings “will likely worsen”.

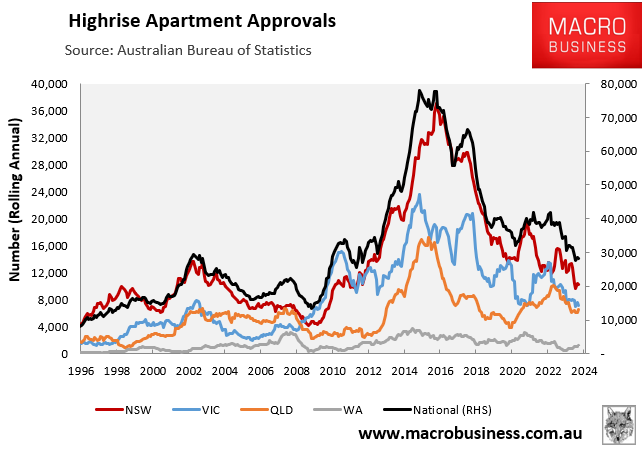

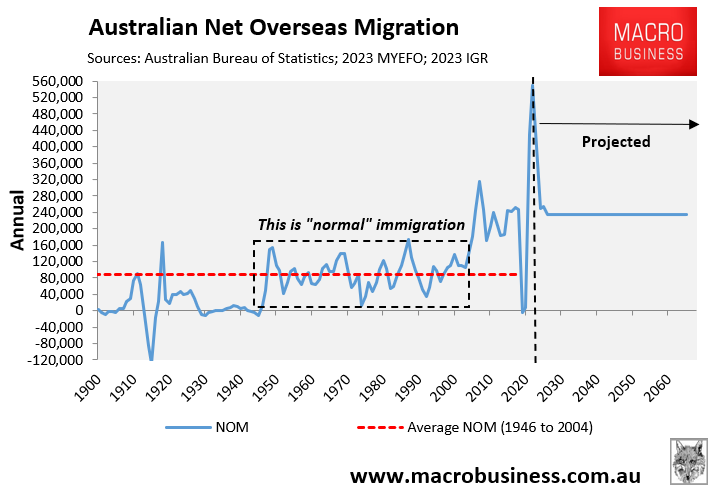

Accelerating shoebox apartment construction to satisfy the federal government’s rapid immigration-driven population expansion will produce results comparable to the previous decade’s high-rise boom.

Build quality will degrade, resulting in the construction of thousands more substandard high-rise shoebox apartments in Sydney and Melbourne.

Congestion will also overrun Sydney’s and Melbourne’s economic and social infrastructure, limiting residents’ access to roads, hospitals, schools, parks, and other public services.

Rather than continuing on this ‘grow at all costs’ path, the NSW and Victorian governments should demand that the federal government decrease net overseas migration to levels consistent with the country’s ability to deliver new housing and infrastructure.

Voters have never backed mass immigration, and the vast majority of Australians oppose it. They also adamantly do not want to live in high-rises.

Our policymakers must stop flooding our cities with people, overloading our housing, infrastructure, water supplies, and living standards.

We already know how this story will end, thanks to the previous decade’s unparalleled apartment boom, which was riddled with defects.

Let us not repeat it.