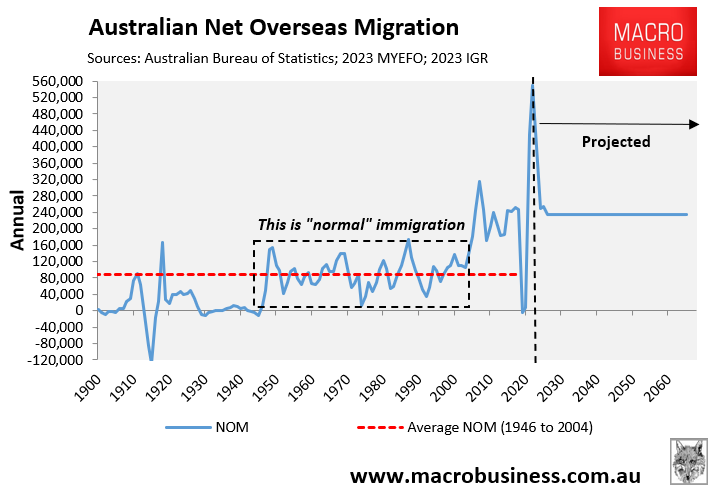

The key macroeconomic data for Australia shows that this century’s immigration boom has been deleterious to the nation’s productivity and living standards.

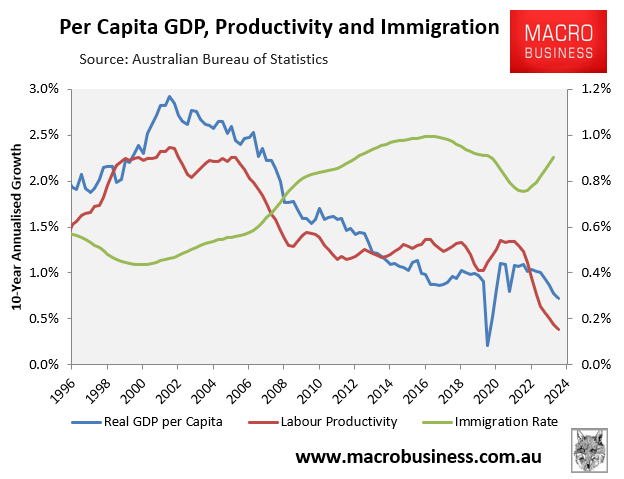

The following chart plots Australia’s long-run trend per capita GDP growth against labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) and the immigration rate (net overseas migration as a share of the population).

Clearly, productivity and per capita GDP growth collapsed after net overseas migration was massively increased in the mid-2000s.

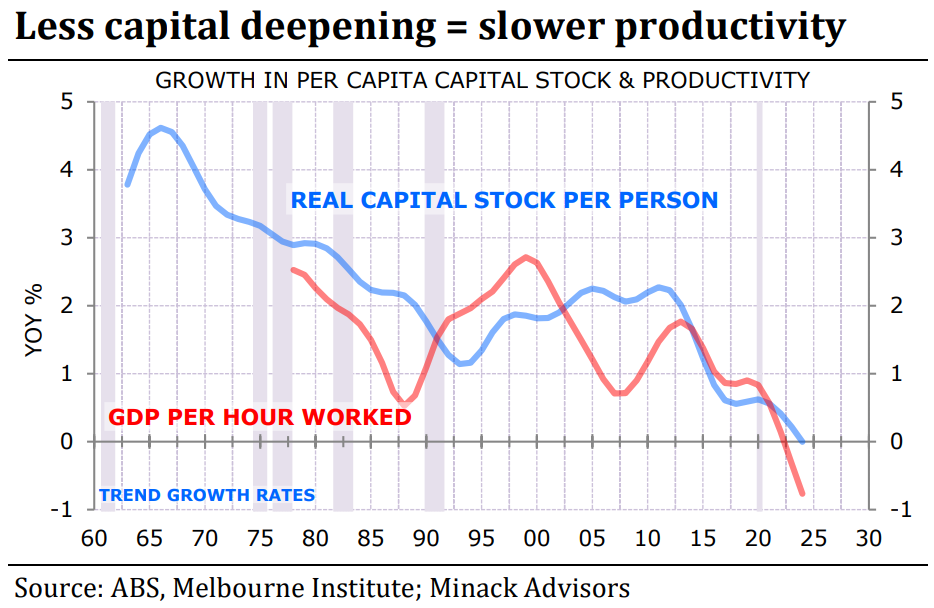

This collapse in productivity is explained by “capital shallowing”, which occurs when a nation’s population grows faster than business investment, infrastructure, and housing, reducing the amount of capital per person.

Independent economist Gerard Minack’s latest analysis, published on Wednesday on MacroBusiness, explained Australia’s capital shallowing in exquisite detail.

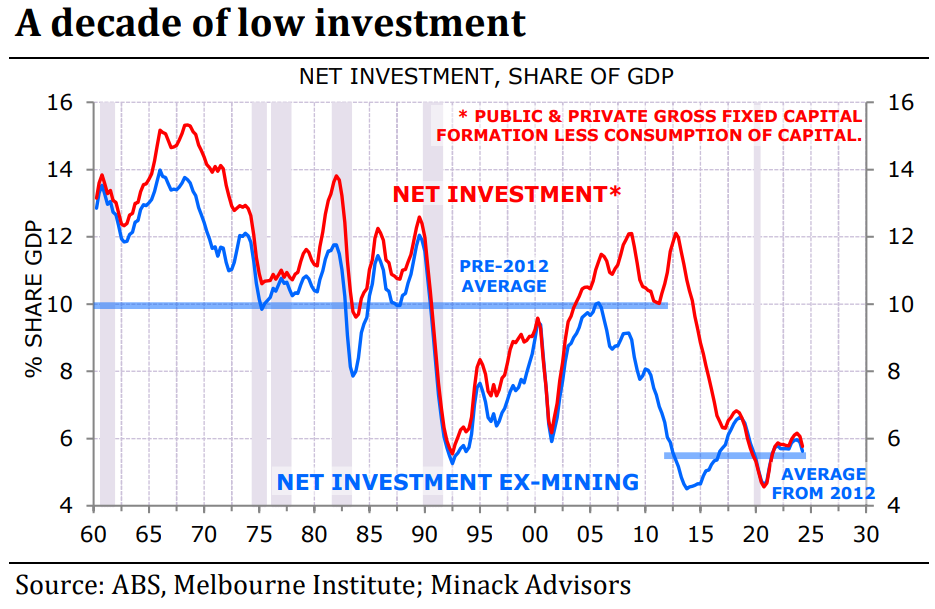

Minack noted that “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

To make matters worse, Minack shows that “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

“Population growth naturally requires investment in public infrastructure and housing. This investment doesn’t improve living standards, it’s required to stop living standards from falling”.

“If investment doesn’t match population growth, then schools, roads and hospitals become more crowded, and housing shortfalls increase house prices and rent”.

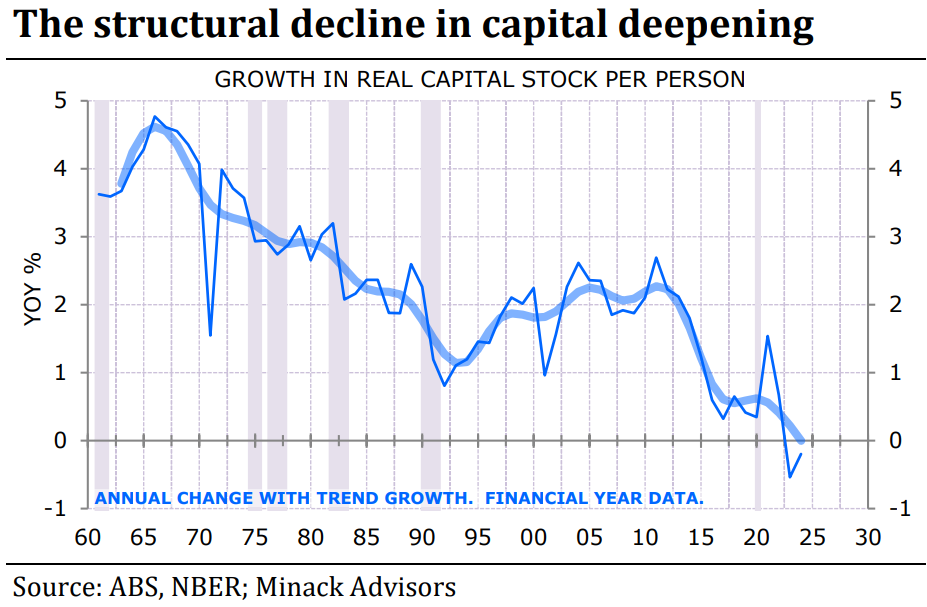

As illustrated by the following chart from Minack, “the fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, according to Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

“The renaissance in Australian productivity from the late 1980s to 2000 was undoubtedly driven by major structural reforms. But it also coincided with the slowest population growth of the post-1945 era”, noted Minack.

Australia is now caught in a productivity ‘catch-22’ as the federal government has committed to permanently high population growth via strong net overseas migration.

We have seen the consequences of this growth in the debate over housing and infrastructure in NSW.

Last month, Mirvac, the NSW Productivity and Equality Commission and Treasurer Daniel Mookey called for less investment in infrastructure to free up labour and resources to build housing.

By contrast, the Committee for Sydney called on the state government to expand infrastructure investment and to build hundreds more Metro, train, and light rail stations to alleviate the housing crisis.

“We need more train stations before we can get more housing”, Committee for Sydney chief executive Eamon Waterford said.

“We should be delivering a new Metro line every four to six years in Sydney”.

“I’m sympathetic that there’s no money but if we are going to solve the long term housing crisis we have no choice”, he said.

The reality is that if the federal government is going to continue expanding the population like an out-of-control science experiment through high immigration, Australia will need massive investment in housing and infrastructure. It is not an either-or proposition.

However, if governments cut back spending on infrastructure and divert it to housing, that will merely substitute one problem for another (and vice versa) and further erode productivity and living standards.

Australia cannot simultaneously have high population growth, high housing investment, and high infrastructure investment.

The optimal solution for Australia’s productivity, housing, and infrastructure woes is to significantly cut back immigration to 1990s levels.

That way, the economy will once again experience capital deepening.