A special roundtable hosted by the Business Council of Australia and The Australian Financial Review heard the views of various housing market players on how to boost the supply of homes.

Lendlease’s Tony Lombardo commented that Australia has a structural shortage of tradies because of the inherent bias for school leavers to go to university.

“It would be great to see more construction workers in hard hats, over suits”, he said.

“For the last 15 years, everyone has been telling their children to go to university – but we need a crew going through the trades”.

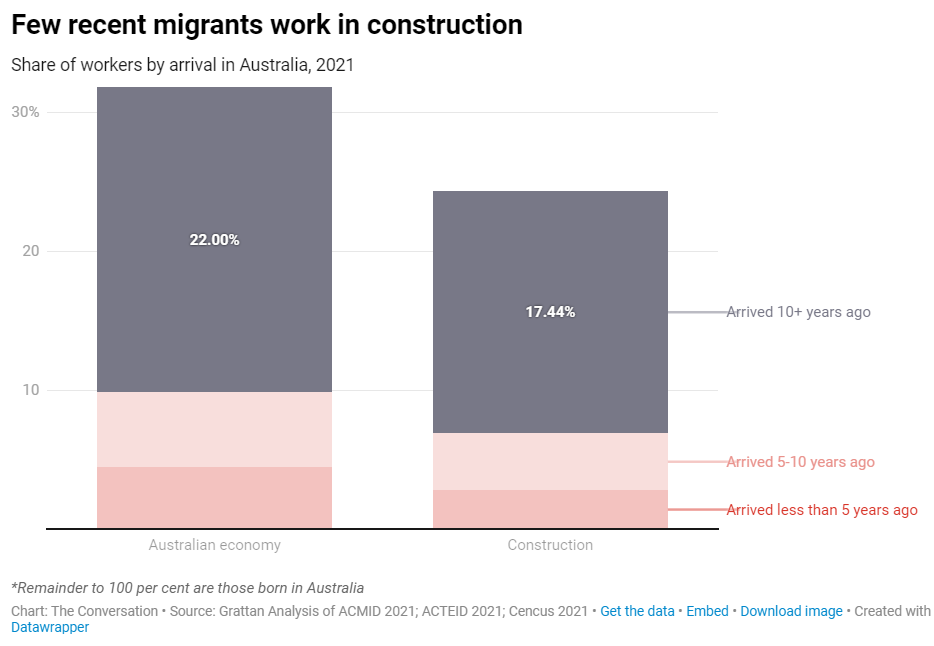

Lombardo wants to see the share of migrants who are construction workers increase to around 10% from only 2.8% currently.

Stockland chief executive Tarun Gupta hit the nail on the head by effectively describing Australia’s housing market as a pressure cooker, forever unable to keep pace with rapacious demand.

“There are capacity constraints. Every time demands picks up, the industry can’t cope”, he Gupta said.

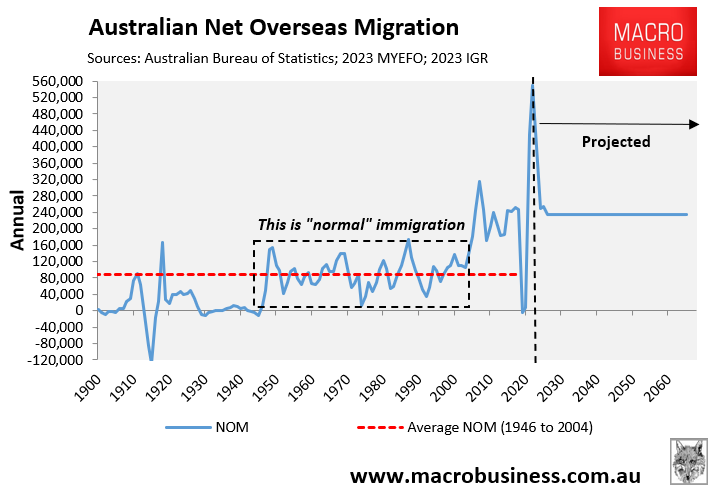

Therein lies the nub of the problem. For twenty years, the federal government has run a high immigration program, which has ensured that demand via population growth has run ahead of the nation’s construction capacity.

Moreover, high immigration is projected to continue indefinitely, as illustrated in the following chart.

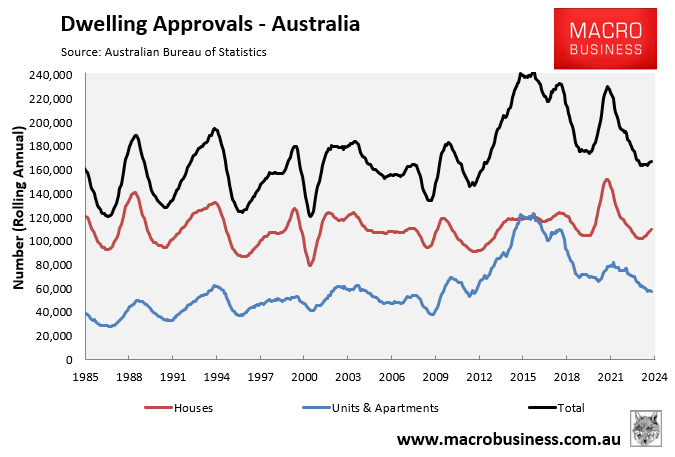

Australia’s housing construction industry is currently supply constrained, which has led to dwelling approvals collapsing to around decade lows.

There is little chance of construction turning around anytime soon, given that interest rates are likely to remain structurally higher going forward.

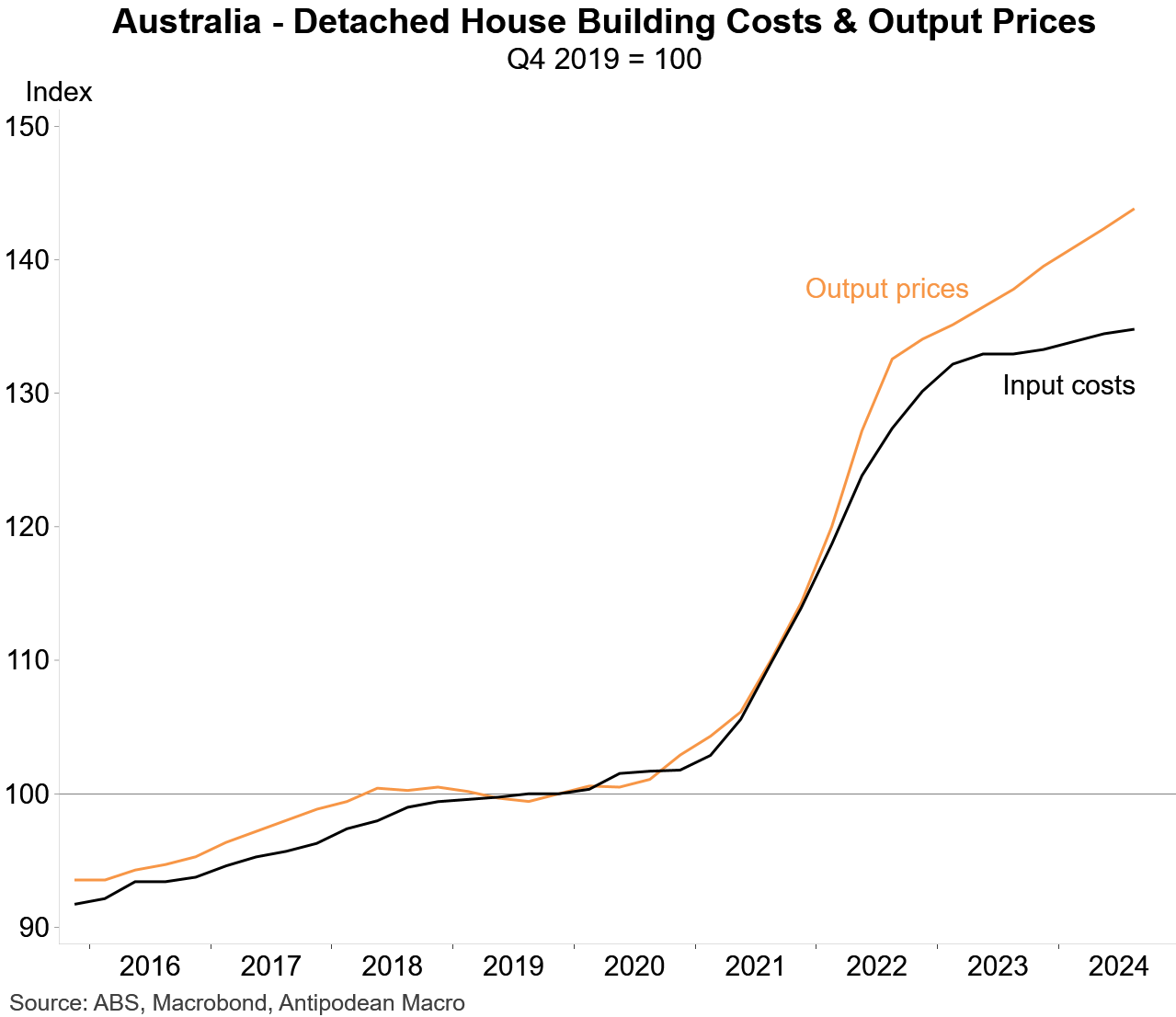

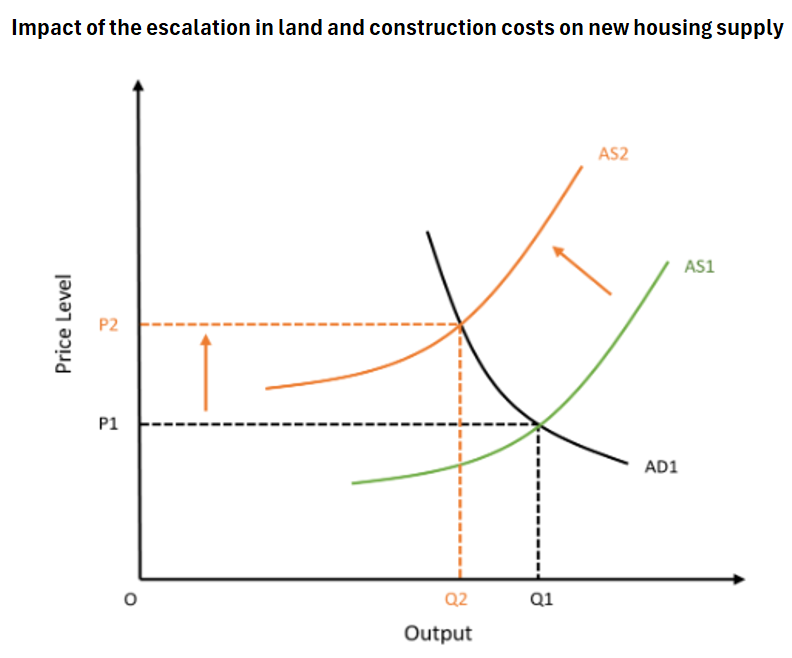

Construction costs—both materials and labour—are around 40% higher than they were pre-pandemic. This has added significantly to the cost of building homes, reducing both buyer demand and supply.

Home builders are competing for labour and materials with government big build infrastructure projects, which has limited capacity within the sector and raised construction costs.

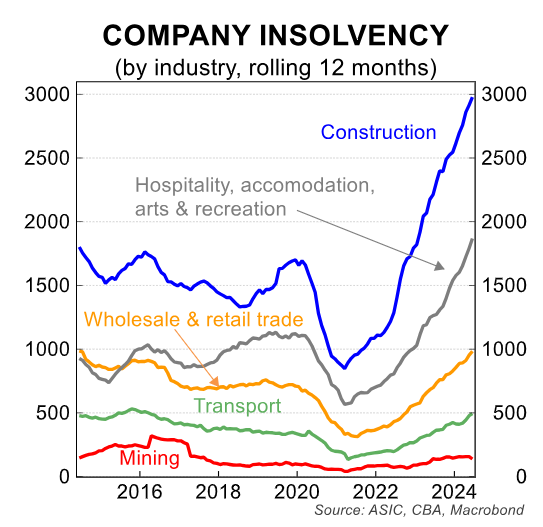

Finally, thousands of home builders have gone bust as profit margins collapsed following the post-pandemic spike in costs.

The upshot is that the above headwinds have effectively shifted the supply curve for housing construction to the left, meaning that fewer homes can now be built at each price point.

While there is certainly merit in shifting Australia’s migration mix towards construction workers, this must be accompanied by a significant reduction in overall immigration numbers.

Demand via population growth must be lowered to match housing supply. Otherwise, Australian housing will forever remain a pressure cooker in crisis.