One of the nation’s least-kept secrets is that most international students come to Australia to “study” because of our generous work rights and opportunities for permanent residency.

Most international students are more interested in working and living in Australia than in learning. And paying course fees is merely the ‘price of admission’.

The student-migration pathway is most evident with private vocational education and training (VET) courses, where providers and student numbers have ballooned, and many are non-genuine.

However, the quality of university degrees has also degraded, which is in line with the explosion in international student numbers.

An article published on Monday in The AFR interviewed several Chinese students who explained how Australian university degrees are considered low quality and easy to get back home.

These students also believed that capping student numbers would increase their quality by making them scarcer and harder to get.

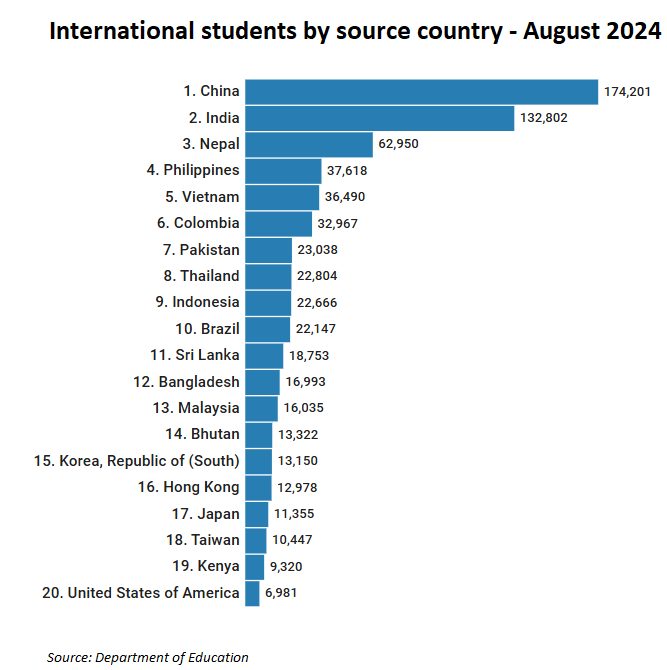

Melbourne University Student Kepuyan Wu explained that Chinese students view Australia as the third most desirable location for higher education on the global stage, after the United States and the United Kingdom.

She said that many Chinese students view Australian universities as more accessible than American and British institutions.

Moreover, Chinese students may end up viewing Australian universities as being more prestigious if international enrolments are capped and places become harder to come by.

Her classmate, Jining Wen, who is also from China, agreed.

“I think setting enrolment caps is a good thing. It improves the required barrier to choosing international students, which could increase the value of the degrees”, he says.

Another Chinese international student, Yuzhe Zhou, who studies at Sydney University, said that some Chinese employers refer to Australian degrees as “shui shuo”, or “water degrees”.

“Some international students report that in China, Australian universities face criticism for their shorter degree duration, being labelled as ‘water degrees,’ implying low academic value and high prestige without substance”, he said.

“As a result, some companies in China might reject applicants with a coursework-based master’s from Australia”.

These comments are from Chinese students studying at Australia’s two most prestigious universities, Melbourne University and Sydney University.

One can only imagine how they would view second-tier universities, home to students from South Asia, who choose Australia mostly for its easy work rights and permanent residency.

South Asian students care about immigration, not education quality.

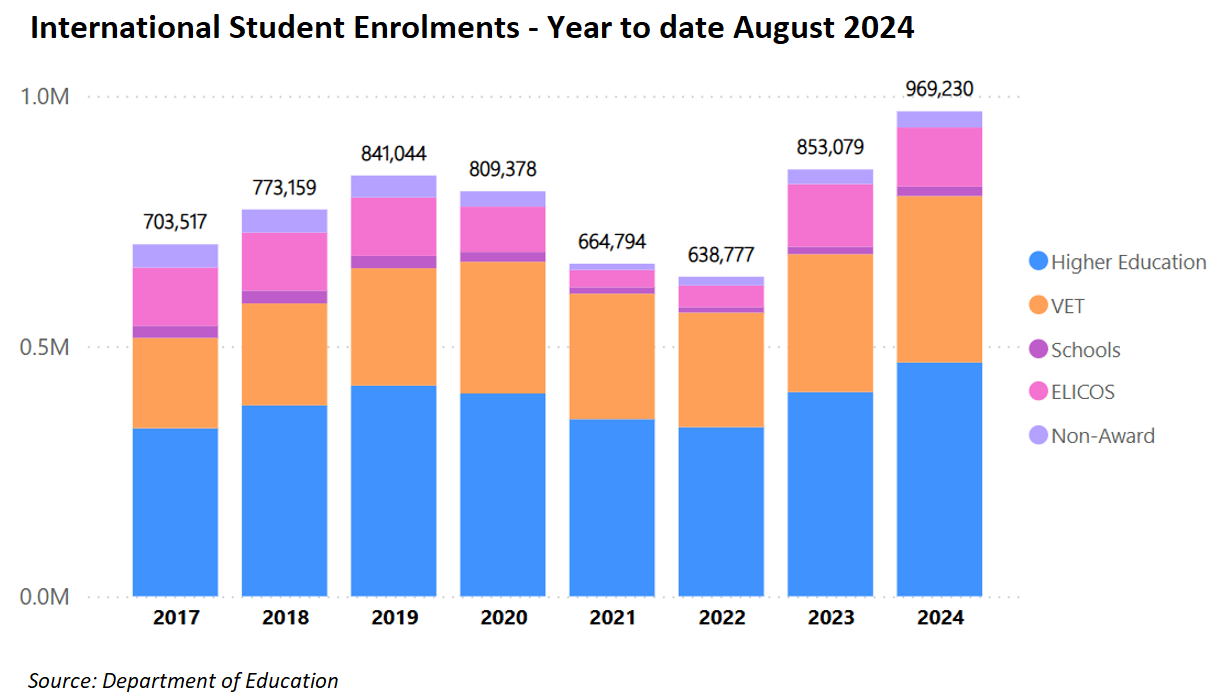

South Asian students have also dominated the growth in international students over recent years.

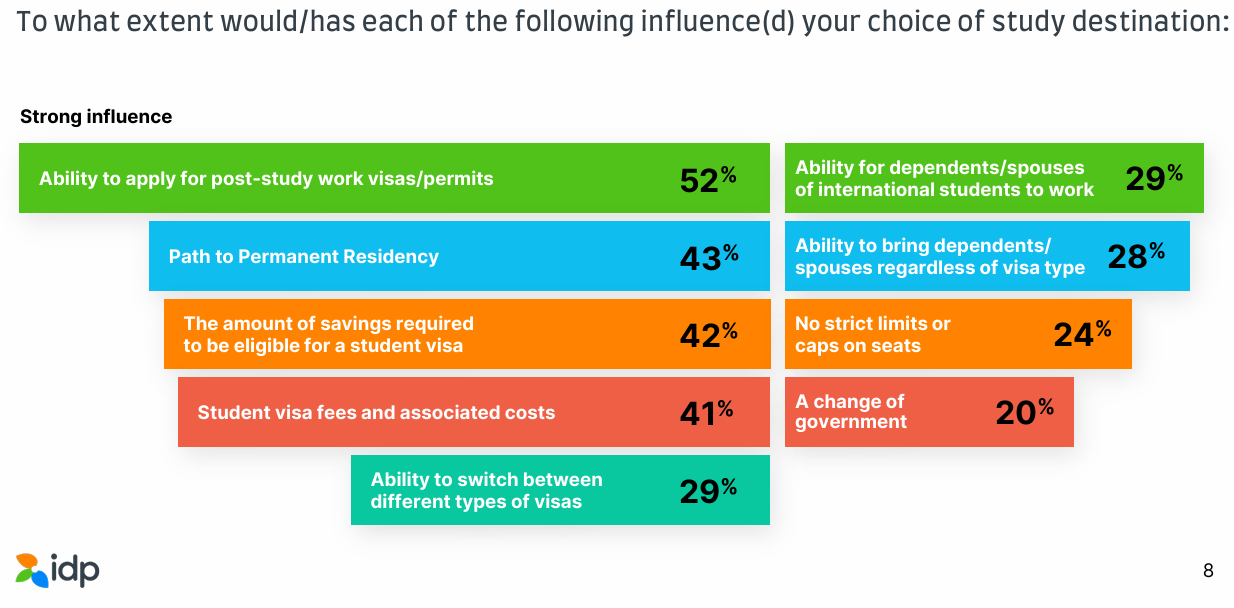

The latest IDP Emerging Futures survey also shows that post-study work opportunities (52%) are the most important factor for international students when choosing a study destination. This is followed by pathways to permanent residency (43%):

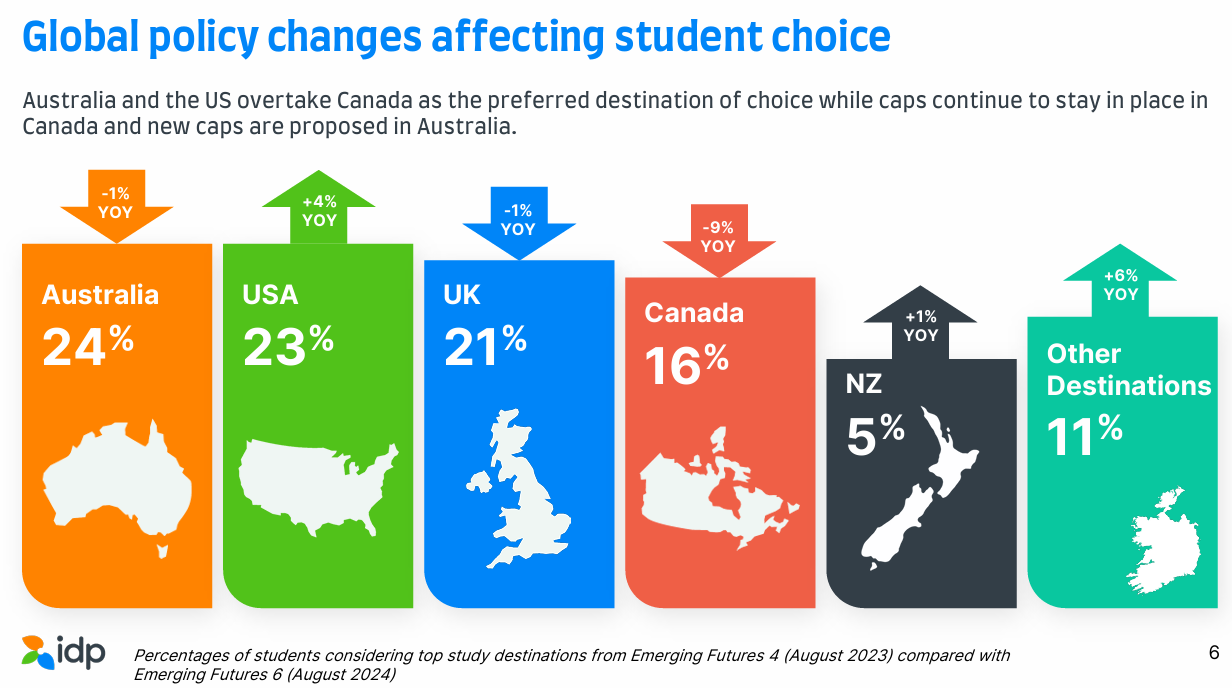

Not surprisingly, then, Australia remains the number one study destination of prospective international students:

According to the surveys above, Australia’s international education trade would collapse if work rights and prospects for permanent residency were severely limited, given that most students’ primary objectives are to live and work in Australia.

Rather than continually lowering standards to lure more international students of doubtful quality to Australia, governments should aim to recruit a much smaller pool of excellent (genuine) students.

This could be accomplished by raising financial barriers to entry, increasing entrance requirements (particularly for English language proficiency and pre-admission testing), raising pedagogical standards, eliminating group assignments, and breaking the link between studying, working, and permanent residency.

These proposed reforms would improve student quality, raise export income per student, improve working conditions in lower-skilled jobs, reduce enrolment numbers, and alleviate population pressures.

Australia’s universities have transformed into degree mills. The higher education system must instead focus on delivering quality over quantity.