Australia’s governments seek to ‘solve’ the housing crisis by forcing residents into high-rise apartments.

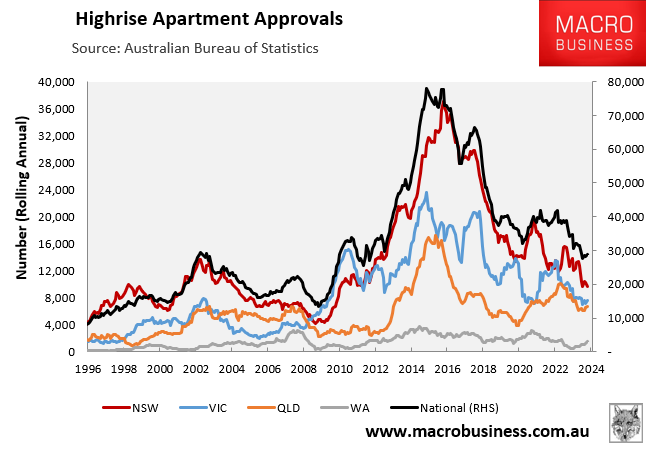

However, high-rise apartment approvals have collapsed, as shown in the chart below:

Since their 2015 peak, high-rise apartment approvals have dropped by 63% across the country, with New South Wales (-74%), Victoria (-68%), and Queensland (-60%) leading the way.

Sydney developer Luke Berry, founder of Thirdi Group, cautioned that the persistent supply shortage and increasing population demand would drive dramatic increases in apartment prices in the coming year.

“Very few apartment projects are going ahead at the moment because it’s very hard to make them stack up due to high costs, so there’s going to be bigger supply issues in the next couple of years”, Berry said.

“I think as soon as interest rates start to fall, maybe middle of next year, there’s going to be renewed interest in new apartments and there’s not going to be enough supply”.

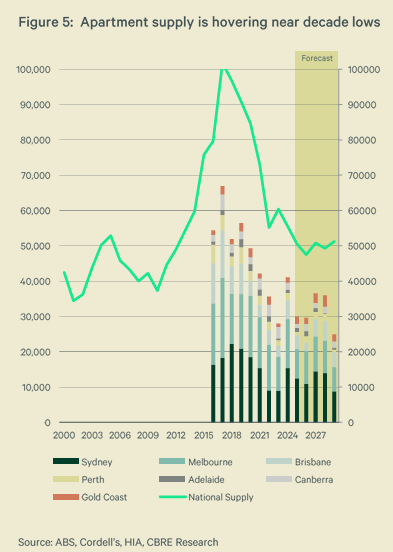

According to CBRE’s most recent forecasts, the national apartment supply will average 50,000 units per year between 2025 and 2029.

This level of building would be around half that of last decade’s peak, and it would be far lower than the rate of supply required to keep up with the expected population increase.

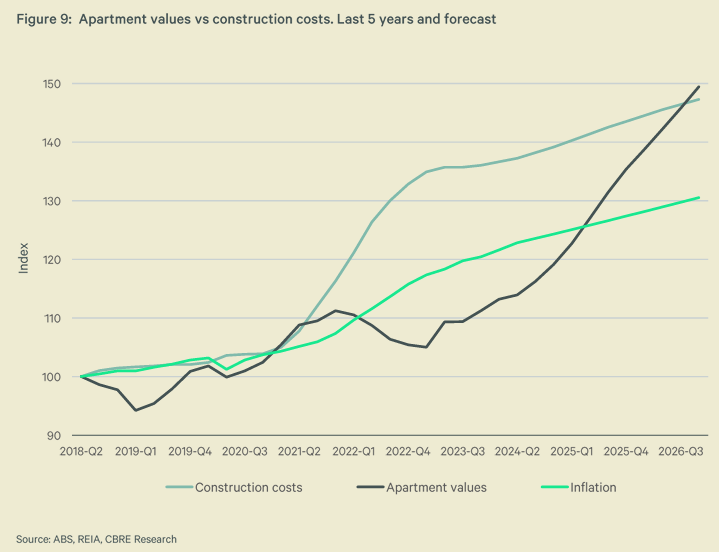

Given the cost increases since the pandemic, CBRE predicted that apartment prices would need to climb dramatically to make construction viable for developers.

“In our view, apartment values will need to accelerate significantly higher to entice developers”, Sameer Chopra from CBRE said.

Charter Keck Cramer also believes that new and established apartment prices must rise for construction to be financially viable. However, such a price increase risks depressing demand from potential buyers.

“Because building costs have jumped by 30% to 40%, prices have to basically go up to be about 30% higher compared to pre-pandemic levels”, Charter Keck Cramer national executive director of research Richard Temlett said.

“The prices of established units need to recalibrate upwards by around 15% for new stock to be accepted by the market at current price points”.

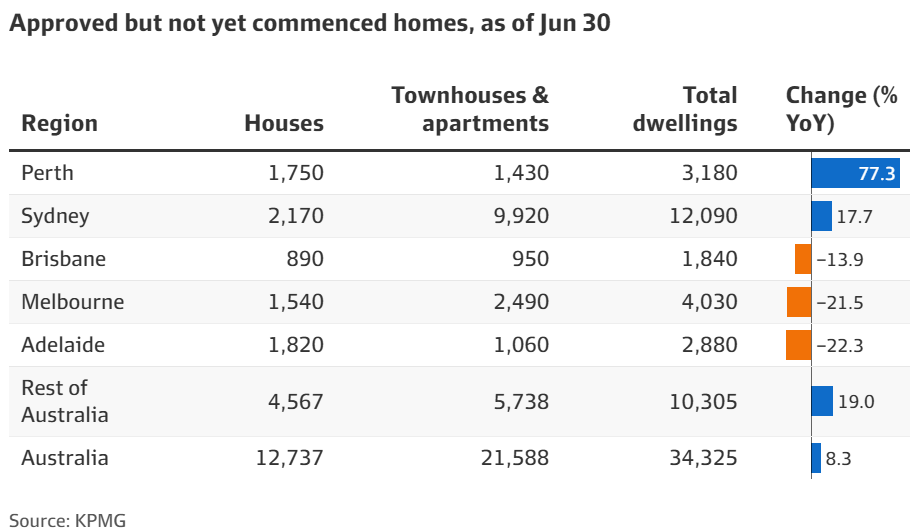

According to a recent KPMG report, more than 30,000 new dwellings have been approved but not yet built across the country, with the majority being apartments and townhouses.

“With all the construction price increases and where interest rates have landed, it’s hard for developers to make those more medium to high-density projects stack up”, explained KPMG urban economist Terry Rawnsley.

“Sometimes people also forget that interest rates also impact on the developer side as well – it means they can’t borrow as much to get the projects up and running”.

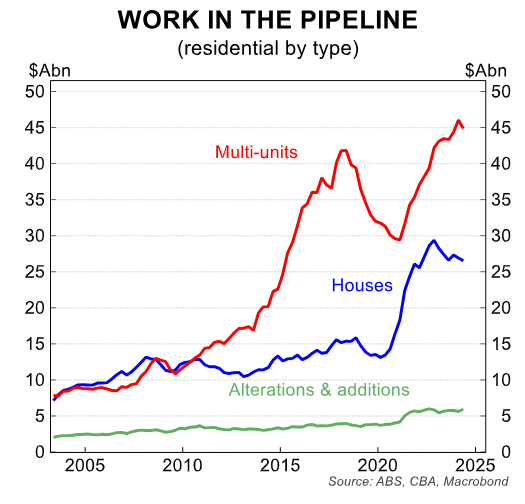

CBA posted the following chart on Wednesday showing the massive pipeline of work to be done on multi-unit dwellings:

“Project viability concerns and constraints in the sector (especially the shortage of labour) has slowed progress on many projects”, noted CBA

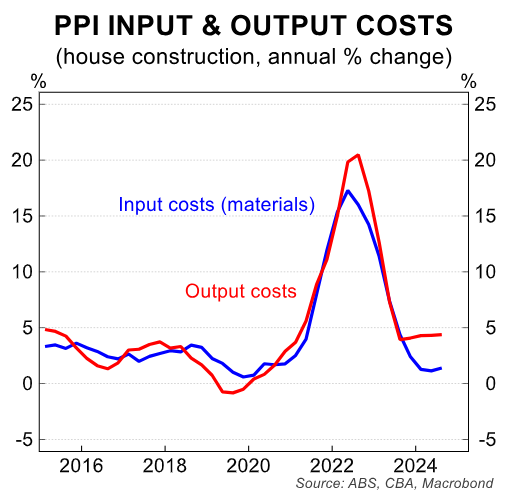

Construction costs have increased by around 40% since the start of the pandemic. Moreover, output costs are still rising at nearly 5% annually.

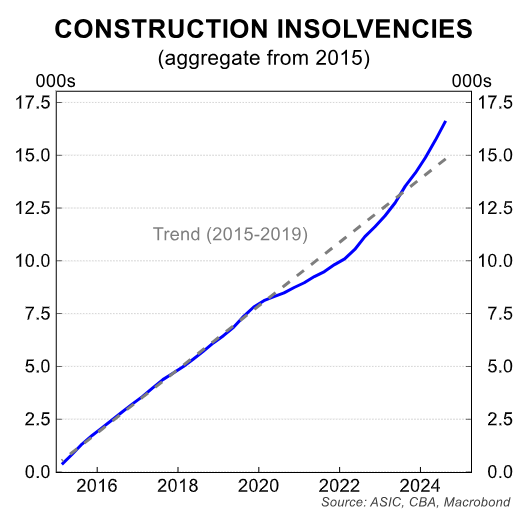

Insolvencies continue to pile up across the construction sector, with thousands of homebuilders going under.

Interest rates are also likely to remain structurally higher for longer, negatively impacting developers and buyers.

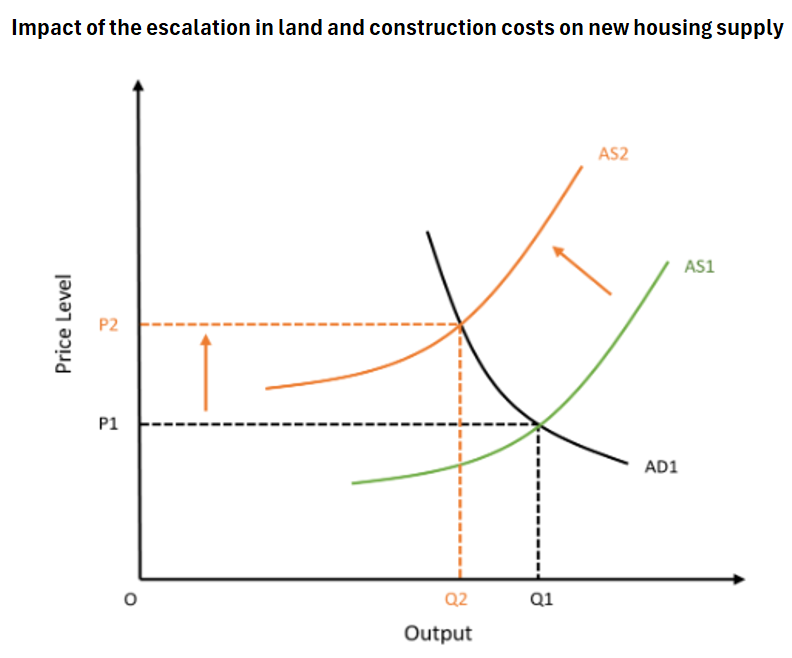

In economic terms, the supply curve for building apartments has shifted to the left, reducing capacity and raising costs.

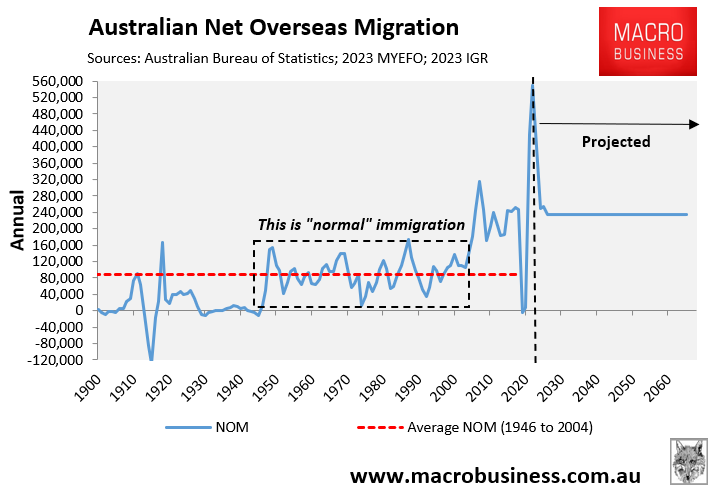

With apartment supply likely to remain stunted, the federal government must restore balance to the market by cutting immigration and reducing population demand.

Otherwise, Australia’s housing will remain in permanent shortage, putting upward pressure on prices and rents.