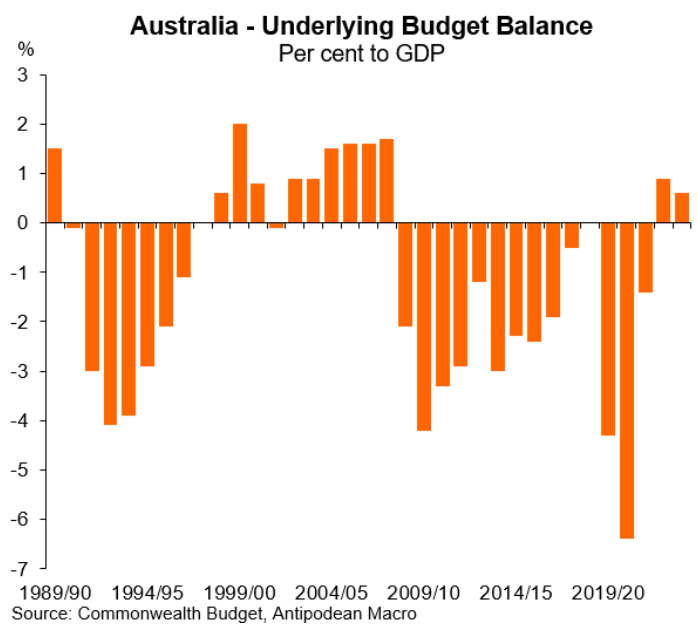

Australian Treasurer Jim Chalmers delivered his Ministerial Statement on the Economy this week, which boasted that Labor has “turned two huge deficits into two substantial surpluses – the first in nearly two decades”.

Chalmers noted that when Labor was elected, “gross debt was projected to be at levels not seen since the aftermath of World War II. Deficits over the forward estimates totalled $225 billion, the highest in any pre‑election outlook”.

Chalmers then claimed credit for “the biggest ever fiscal turnaround in a single term”, meaning “the budget was $172 billion better off”.

“This record turnaround hasn’t been accidental or incidental”, Chalmers boasted. “We have been able to save around $80 billion in interest payments compared to the 2022 PEFO over the decade to 2032–33”.

However, Chalmers advised that budget storm clouds are building on the horizon, noting that “the Chinese economy [is] weighing on key commodity prices – iron ore prices are down 30% since the start of the year”.

“As a result of these factors, I can inform the House that Treasury expects any revenue upgrades in the mid‑year outlook will be much smaller”.

“At this stage, Treasury is also expecting to revise down company tax receipts – for the first time since 2020”, Chalmers warned.

Independent economist Chris Richardson argued on Twitter (X) that “the carnival is over” for the federal budget.

Richardson noted that since the government came into office, estimated revenues over a four-year period have been revised up by one-third of a trillion dollars.

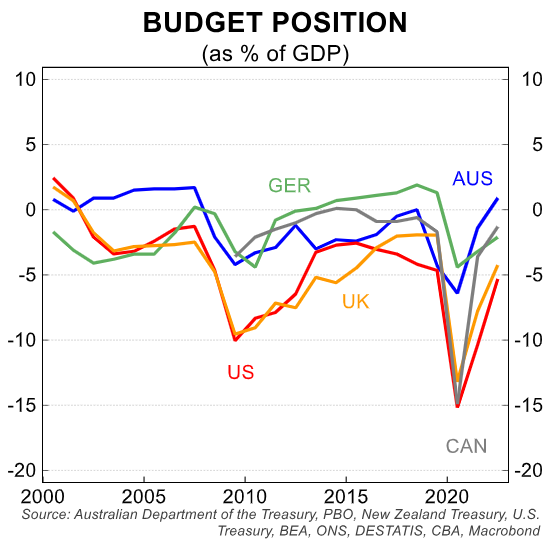

However, the windfall is not due to explicit government decisions on spending and taxes. Instead, it is due to war, strong immigration, and inflation.

War drove up the price of products Australia sells to the world, such as iron ore, coal, and LNG. As a result, the tax pie grew larger (especially company taxes).

Record levels of immigration saw the number of taxpayers balloon, which meant that the federal government collected far more in personal income taxes (most of the fiscal costs of immigration fall on the states).

Finally, bracket creep and the expiry of the lower-middle income tax threshold pushed up average tax rates, meaning that households received less and the tax office got more.

Richardson warns that the positive headwinds for the budget are fading or reversing.

Iron ore prices are down, inflation is down, and immigration is reducing.

President Trump’s China tariffs could also reduce demand for Australian commodities, reducing the company tax take and imported inflation.

“Like Paris Hilton, the budget has been ‘sliving’ until now – it’s been “slaying mixed with living its best life”, Richardson wrote on Twitter (X).

“But the transition from ‘sliving’ to ‘sliver’ means that the carnival is over”.

“In fact, if I were doing the Treasury estimates of the coming tax take, I’d be edging them lower, not higher”.

“That says the choices we make as a society are about to lose the cushion we’ve enjoyed in recent years”, Richardson said.

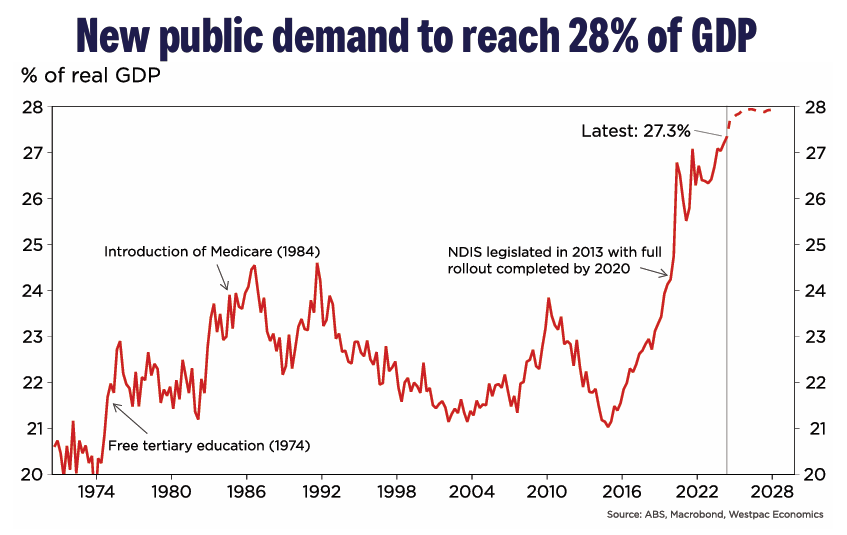

The windfall tax gains have been hypothecated through record government spending on things like the NDIS.

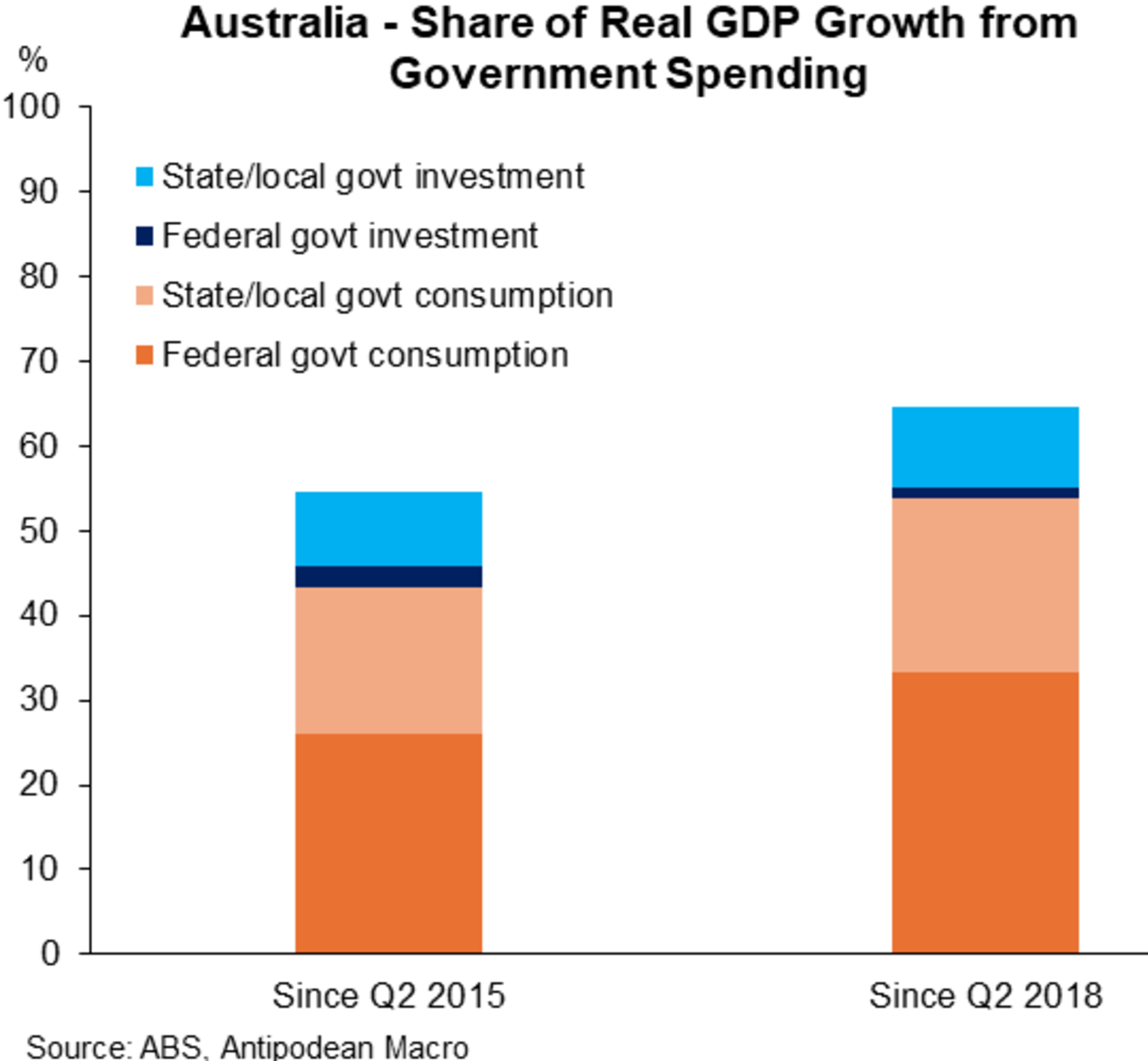

This record government spending has accounted for more than half of real GDP growth since mid-2015 and nearly two-thirds since mid-2018.

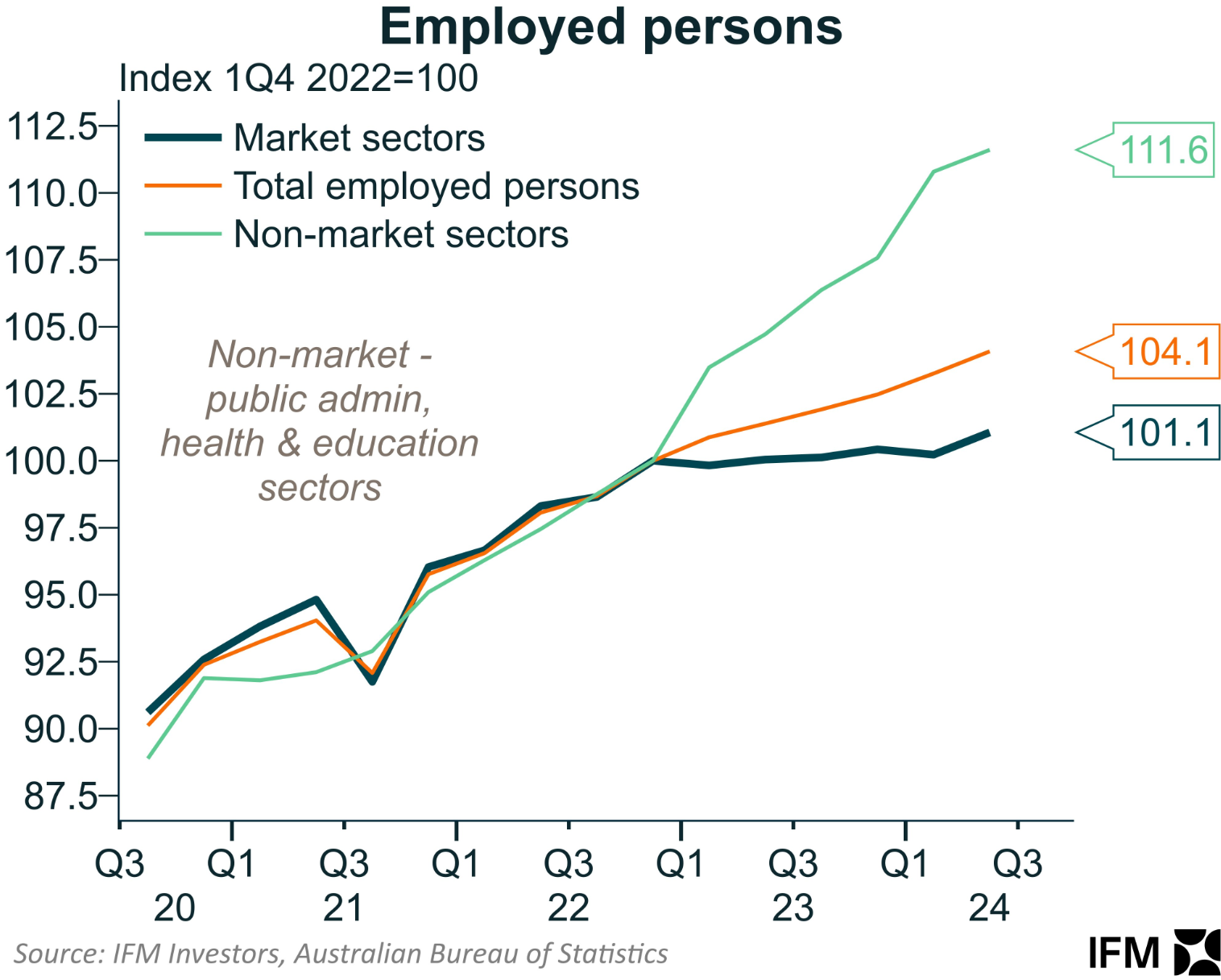

The non-market (government-aligned) sector has also driven nearly all of the nation’s job growth since Q4 2022:

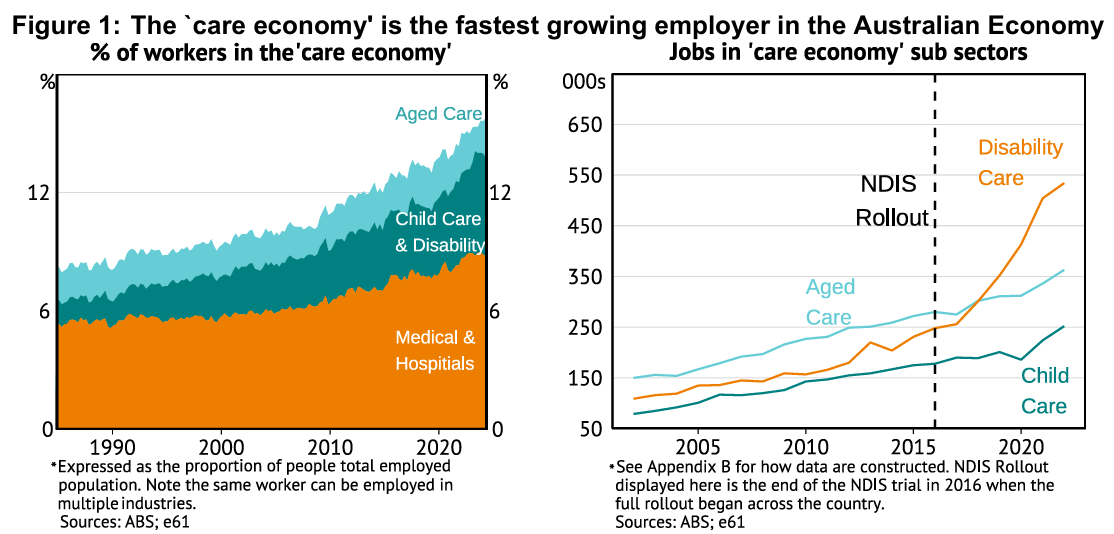

Most of this non-market job growth has been via the NDIS:

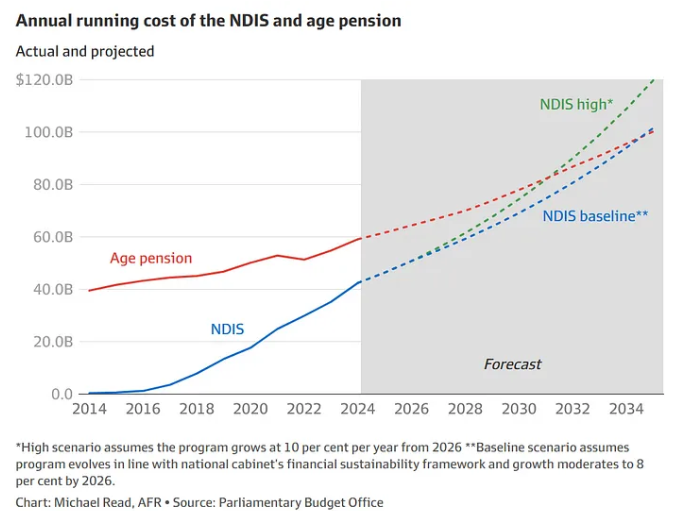

Given that the NDIS is projected to roughly double in size in nominal terms over the coming decade to $100 billion annually, we must ask ourselves: where will the revenue come from?

Running a ‘tax and spend’ economy is only viable when sources of revenues are expanding. However, those rivers of gold are about to run dry.

This weekend’s interview with Radio 2GB discussed these issues in detail.