A few years back, Australia made headlines for having the 93rd most complex in the world, with its closest rival being Uganda.

The latest Economic Complexity Index rankings from the Growth Lab at the Harvard Kennedy School show that Australia has plunged further down from 93rd to 102nd out of 145 countries.

Australia’s economic complexity has fallen just behind Bangladesh (100) and Senegal (101).

“You have fallen just behind Bangladesh and Senegal in what you’re able to produce within your goods exports today… Also, Australia has fallen from its ranking of 63rd in the year 2000”, Tim Cheston, Senior Research Manager at the Growth Lab, told @AuManufacturing.

“So again, falling from 63rd to 102nd shows that we’re consistently going in the wrong direction within this measure of economic complexity”.

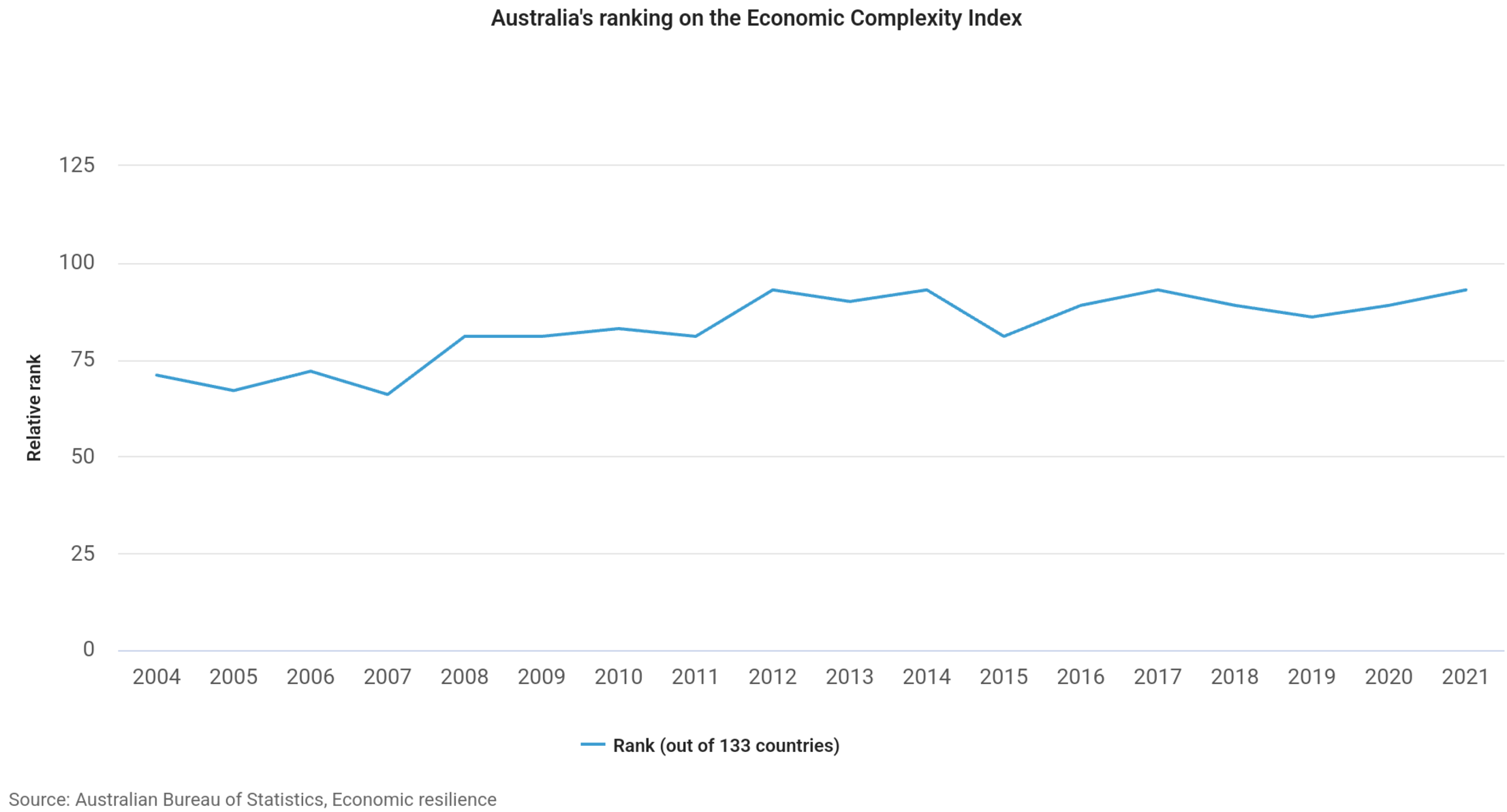

Independent economist Tarric Brooker created the following chart showing the structural decline in Australia’s economic complexity over the past 20 years:

Chart by Tarric Brooker

The Growth Lab website states, “Australia is less complex than expected for its income level. As a result, its economy is projected to grow slowly”.

“The Growth Lab’s 2031 Growth Projections foresee growth in Australia of 1.7% annually over the coming decade, ranking in the bottom half of countries globally”.

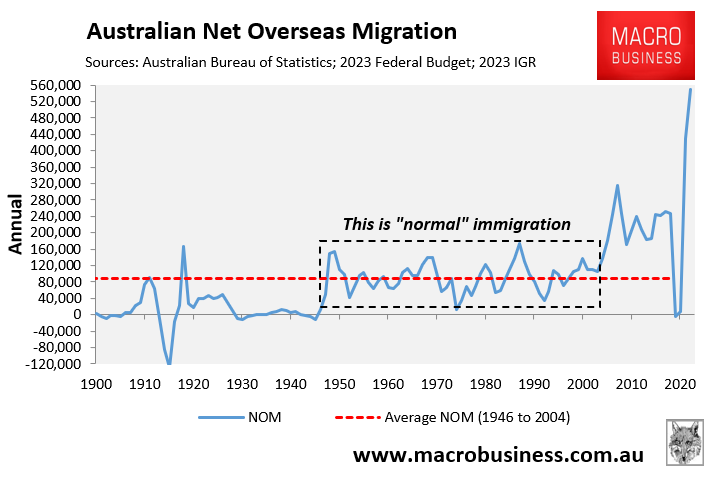

The decline in Australia’s economic complexity has coincided with the collapse in Australia’s manufacturing share and the record boom in net overseas migration.

The most sophisticated countries have significant manufacturing (tradeable) industries. Most of these economies do not rely on immigration (population expansion) to propel them forward.

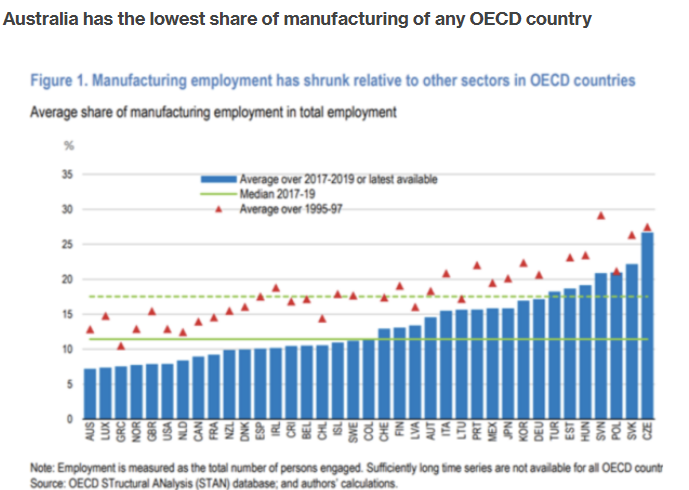

In contrast, Australia has allowed its manufacturing sector to collapse, resulting in the OECD’s lowest manufacturing share.

Source: OECD

The collapse in the manufacturing sector has been facilitated by energy policy failures, which, despite Australia being rich in coal, gas, and sunlight, have delivered Australians some of the most expensive energy costs in the world.

This year, we have already witnessed Qenos—Australia’s last plastics manufacturer—shut down due to high energy prices.

Multiple other major manufacturers, including Nestle and PepsiCo, have also threatened to leave Australia due to high energy costs.

How can Australia expect to be competitive in manufacturing with high-cost energy due to policy failure?

Instead of focusing on productivity-driven growth, Australia has relied on importing hundreds of thousands of people each year, combined with rising household debt, to fuel spending and malinvestment in real estate and catch-up infrastructure.

By adopting a mass immigration strategy, Australia has fostered growth in low-productivity ‘people-servicing’ businesses while diverting the country’s productive effort away from business investment and towards housing and infrastructure.

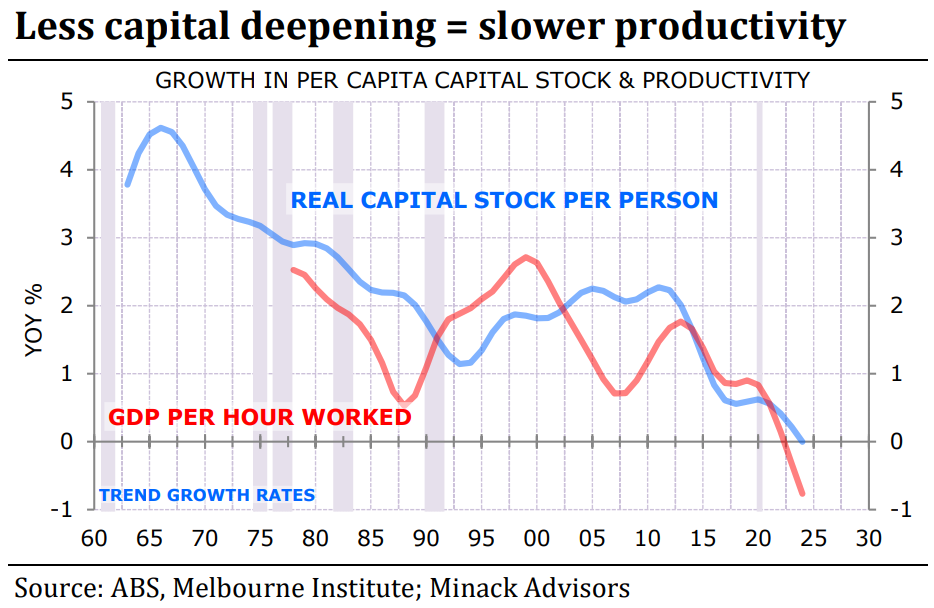

This mass immigration policy has created ‘capital shallowing’ and reduced productivity.

Perversely, growing the nation’s population by 8.5 million this century has also diluted Australia’s mineral base, the primary source of the nation’s wealth, making Australians poorer per capita.

This is different from how smart, sophisticated countries operate. They grow by prioritising quality productive growth above quantity-based ‘dumb’ population expansion.

Simply adding more people to work in low-productivity service industries, many of which are government-funded, is not a viable economic model and will not improve Australia’s living standards.