Australia’s productivity recession deepens

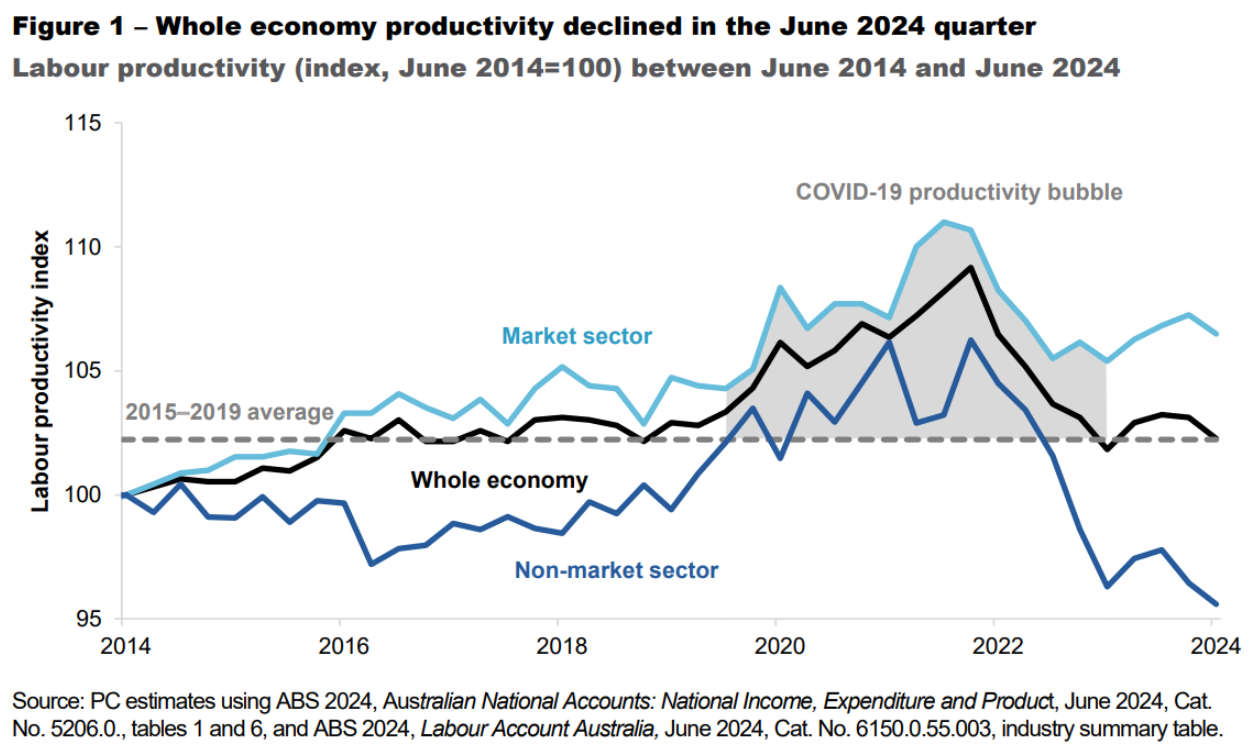

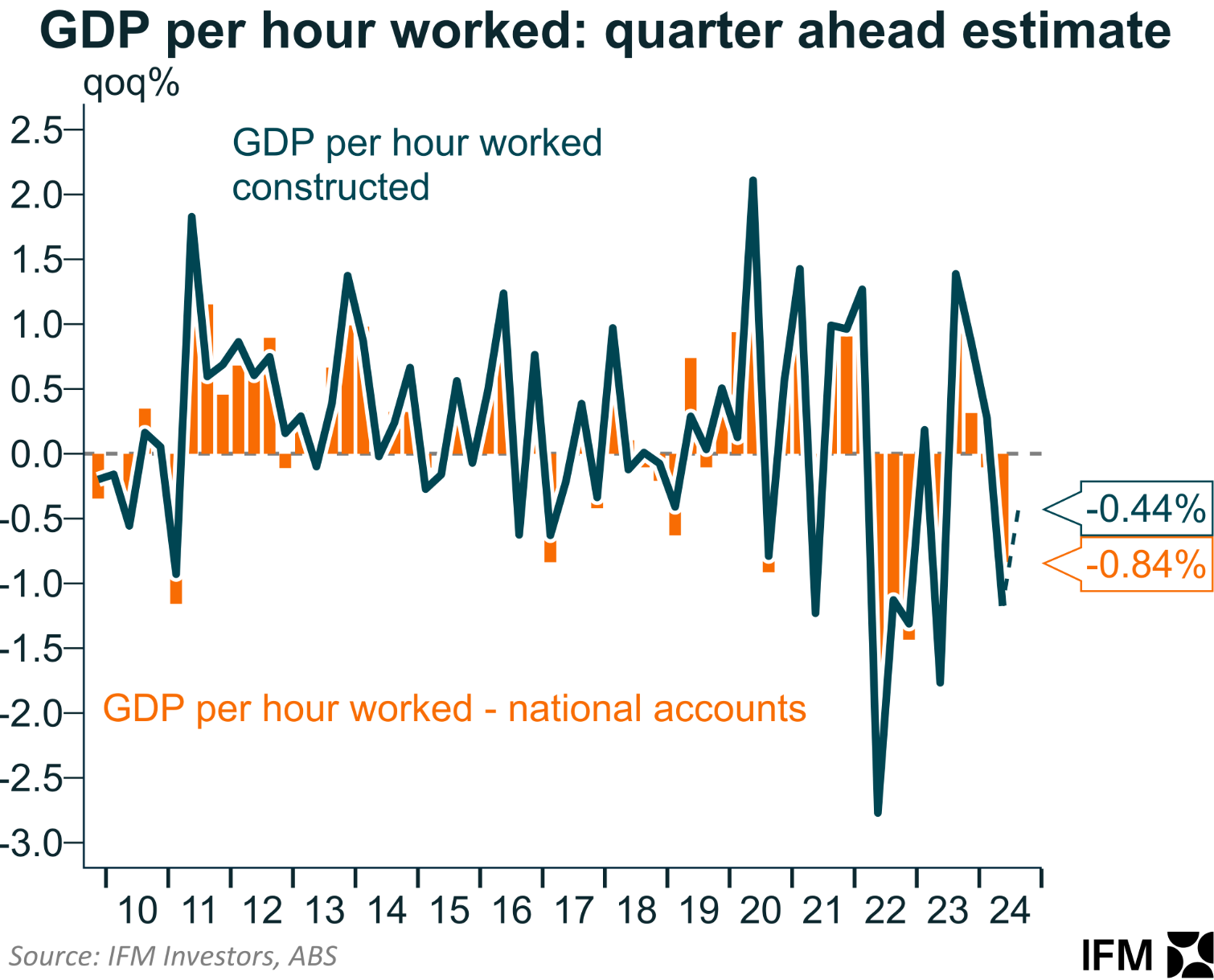

The June quarter national accounts showed that Australia’s labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) fell to 2016 levels, driven by the non-market sector.

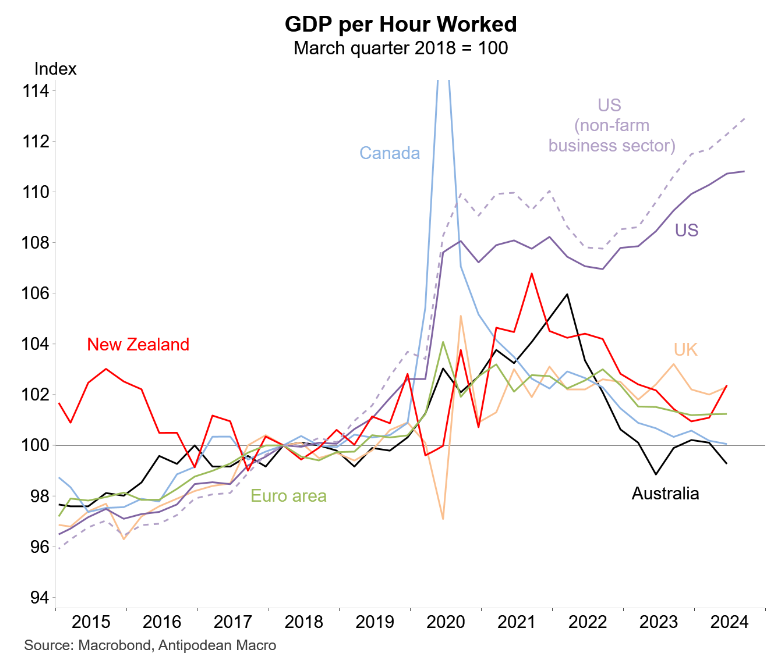

Australia has also experienced the most significant decline in GDP per hour worked since Q1 2018 out of advanced English-speaking nations and Europe.

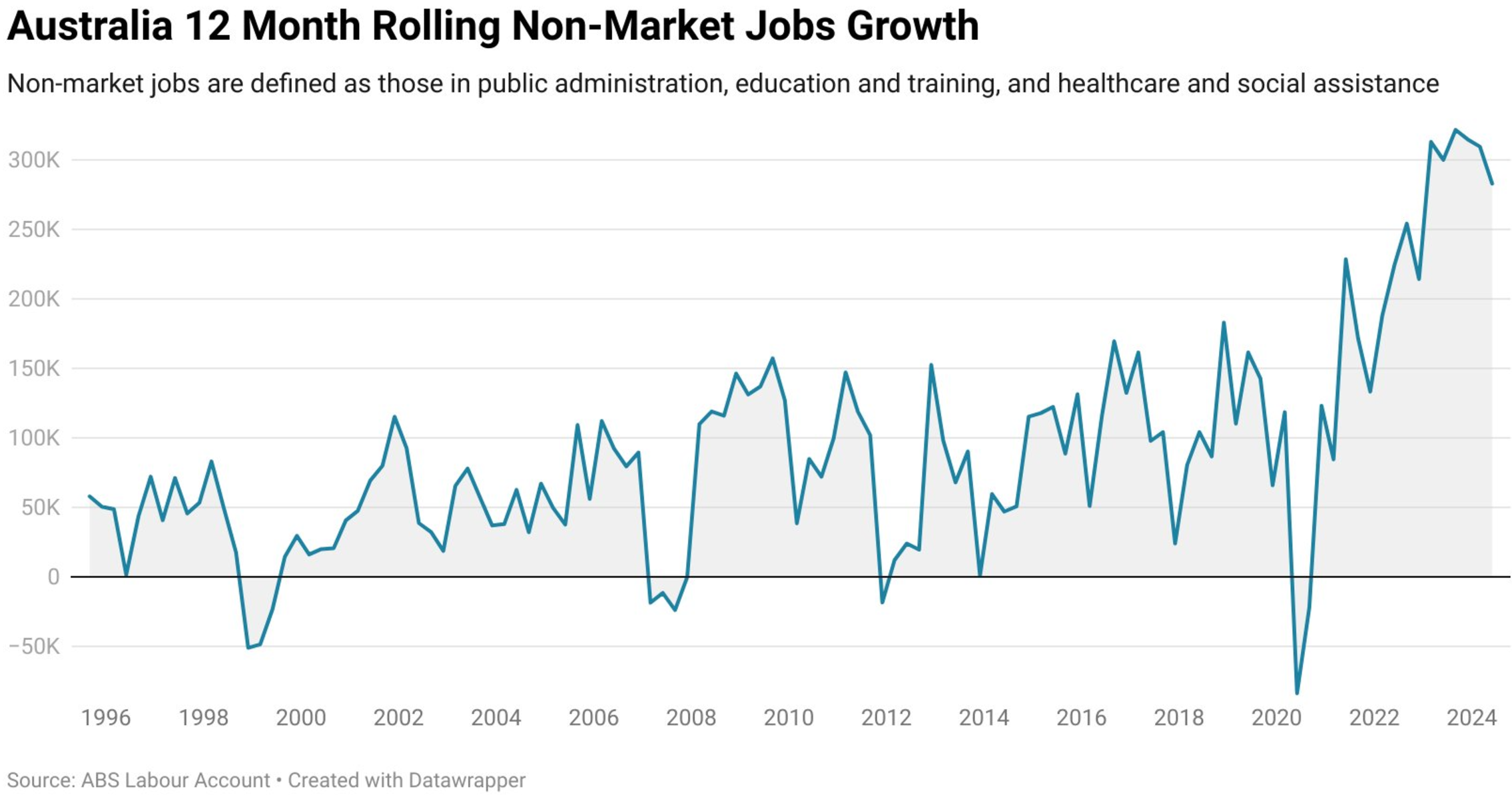

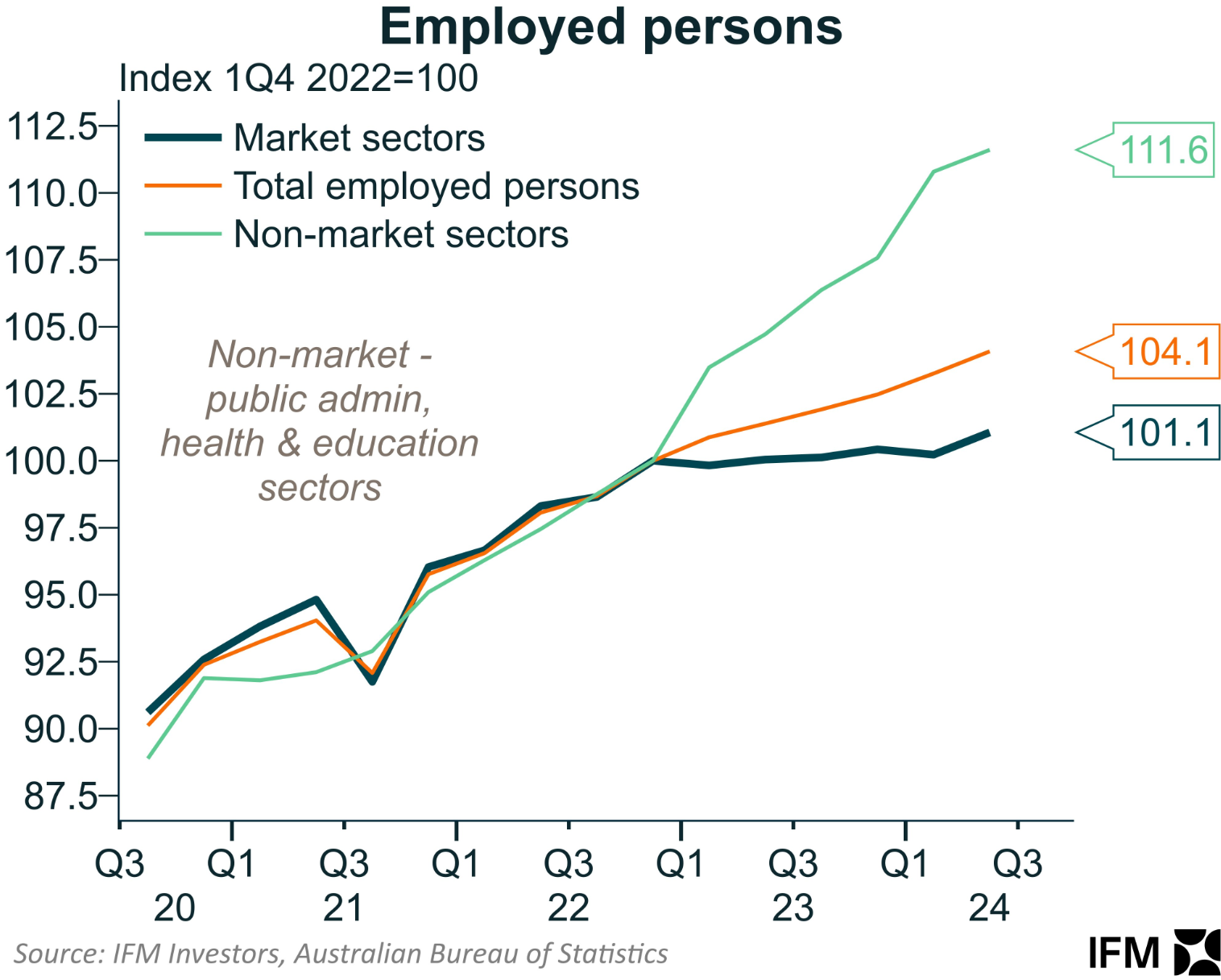

Australia’s productivity decline followed an astronomical rise in non-market (government-aligned) jobs, including private companies whose funding is mainly from government spending.

Chart by Tarric Brooker

The expansion of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) has been the primary factor driving the surge in non-market jobs.

Indeed, since Q1 2022, overall employment across the Australian economy has grown by 4.1%.

Almost all of this job growth has come from the non-market (government-aligned) sector, which expanded by an extraordinary 11.6%. In comparison, job growth across Australia’s market sector has stagnated, growing by only 1.1% over the same period.

IFM Investors chief economist, Alex Joiner, posted the following chart on Thursday, constructed from the October Labour Force release from the ABS, suggesting that Australia’s labour productivity declined again in Q3:

Joiner’s calculation assumes that the market forecast for GDP growth of 0.4% in Q3 comes to fruition.

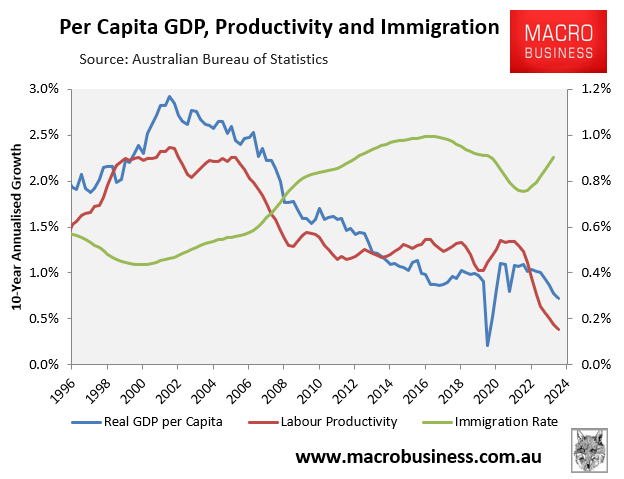

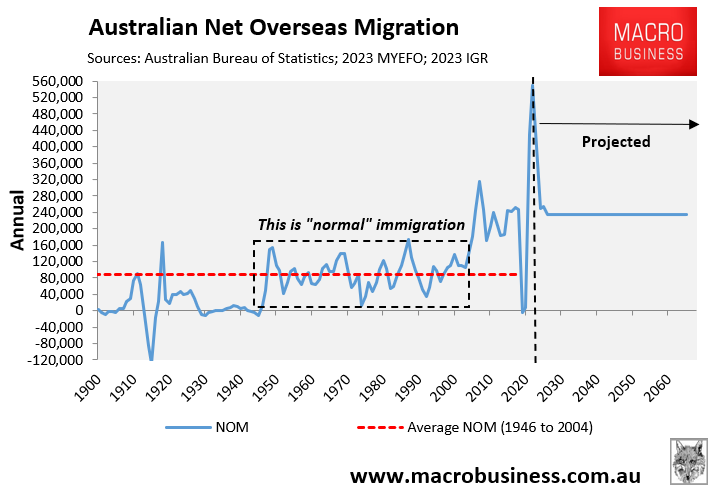

Australia’s longer-term productivity decline also coincides with the ramp-up of immigration in the mid-2000s.

The federal government more than doubled Australia’s net overseas migration, negatively impacting productivity through what economists call “capital shallowing”.

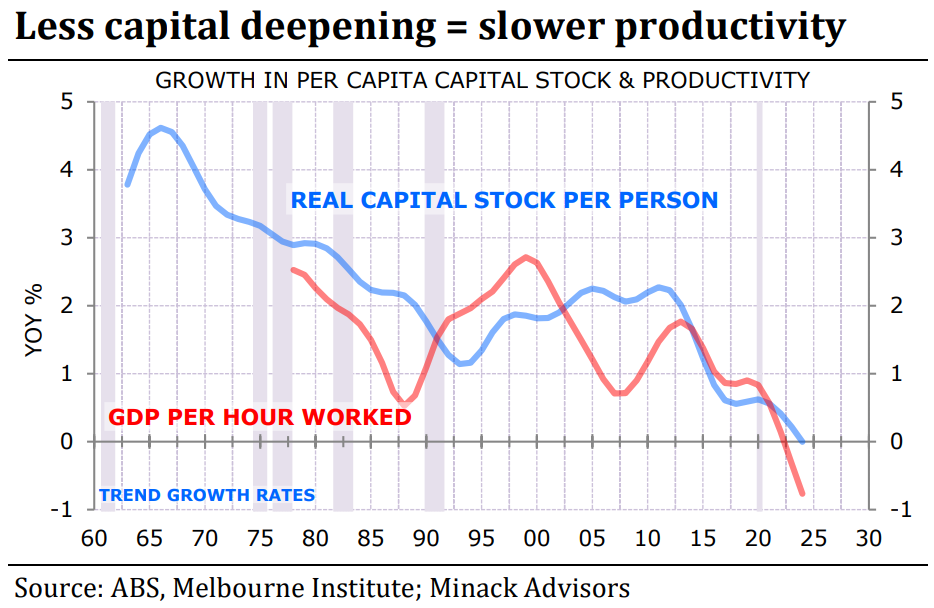

When a country’s population growth outpaces its business, infrastructure, and housing investment, it produces less capital per worker, making it less productive and slowing its per capita growth rate.

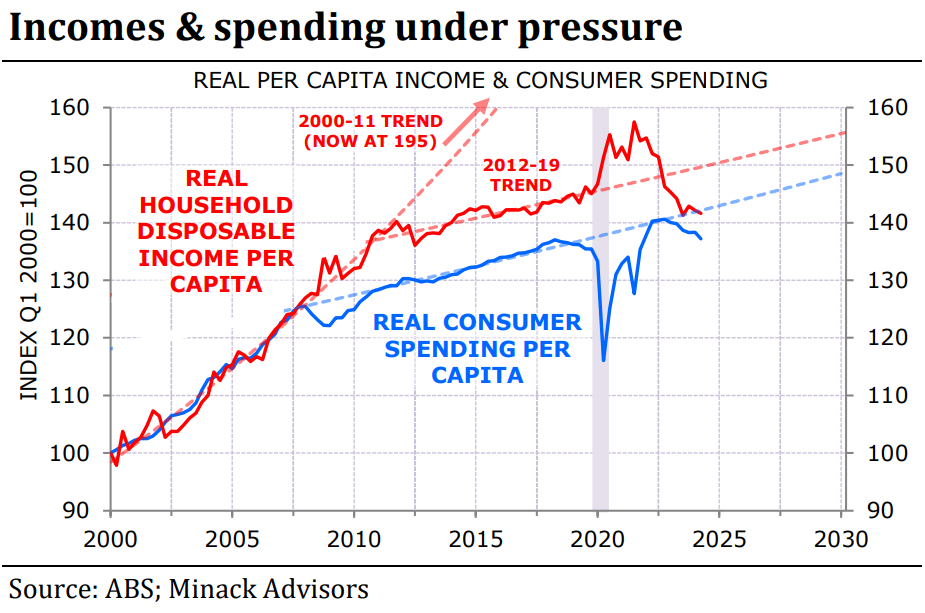

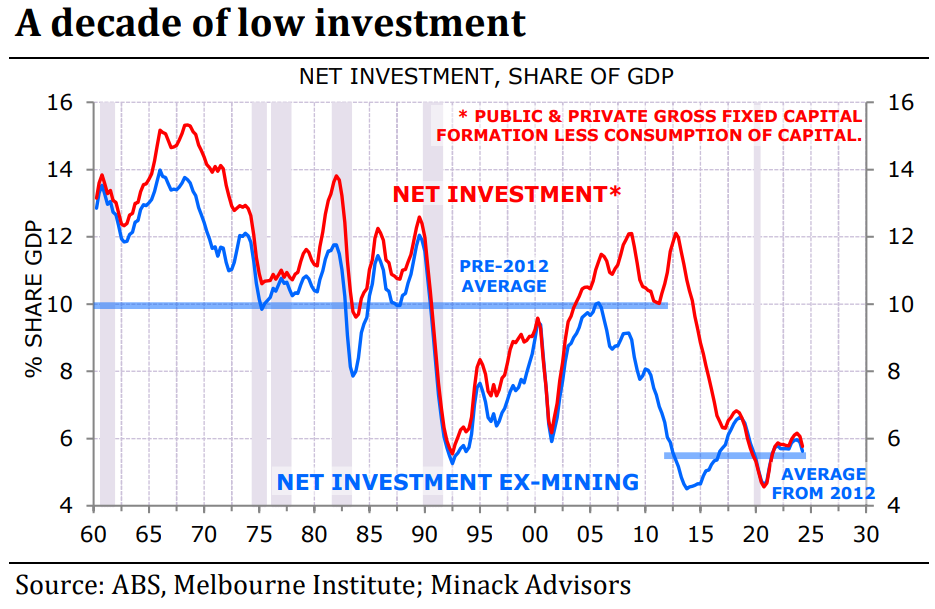

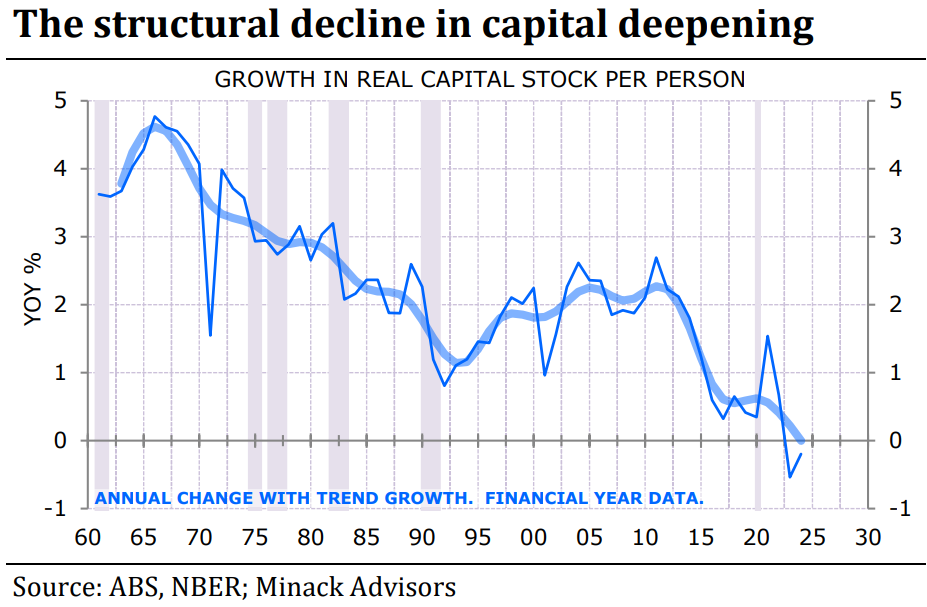

Independent economist Gerard Minack showed last week that Australia’s “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

To make matters worse, Minack showed that “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, noted Minack.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

Thus, Australia is now caught in a productivity trap because the federal government has committed to running a permanently high immigration program, which will inevitably result in more capital shallowing (or at least less capital deepening).

Unless productivity growth magically picks up, Australia faces low economic and income growth in the 2030s.