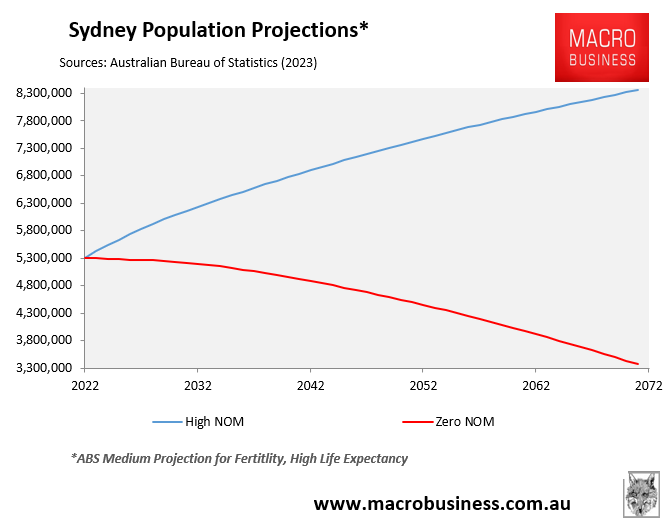

I have always said that water is the ‘elephant in the room’ of the immigration debate that policymakers and pro-Big Australia boosters never address.

A procession of reports over recent years has warned that Australia faces chronic water shortages and rising costs as its population swells by millions on the back of permanently high levels of immigration.

For example, a 2021 report by the Productivity Commission (PC) warned that the projected 11 million increase in population across Australia’s cities “present significant risks to the security of Australia’s water resources”.

“Climate change and population growth present significant risks to the security of Australia’s water resources”, the PC warned. “Drought conditions are likely to become more frequent, severe and prolonged in some regions”.

“Higher anticipated demand from a growing population, alongside reductions in supply, will increase water scarcity and put further pressure on all users (including the environment)”.

“By 2050 an additional 11 million people are expected to live in capital cities, and almost half (45%) of all Australians will live in Sydney and Melbourne (up from 41 per cent in 2019)”, the PC projected.

“In major cities where readily-available supply sources have already been accessed, ongoing population growth is likely to create significant pressure on water supplies”.

“Major supply augmentations will often be needed. Scenarios developed for Melbourne, for example, include a worst case of demand outstripping supply by around 2028”, the PC warned.

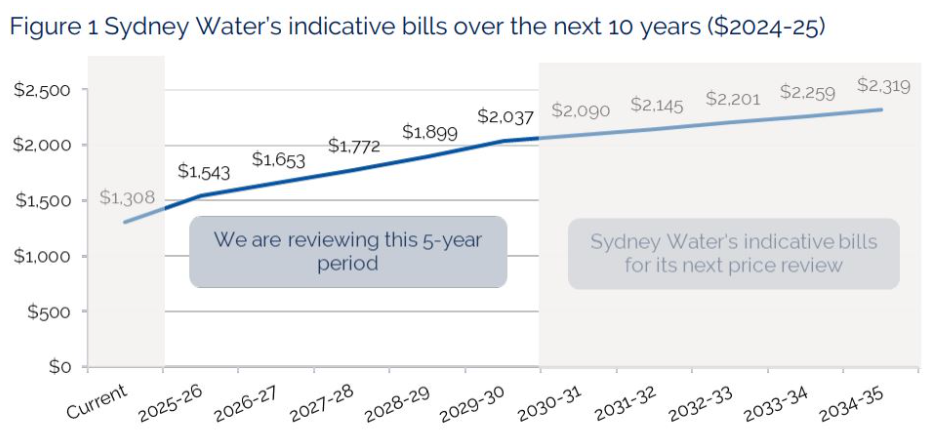

Earlier this month, Sydney Water revealed that it is seeking to increase water prices by 50% over five years largely in response to population growth.

Source: Sydney Water

As reported by the ABC:

The NSW government has forecast Greater Sydney will add more than 170,000 new homes by 2029.

Sydney Water said 60% of the $16 billion it raised by the end of the decade would be invested in delivering new services across growth areas.

This included north-west Sydney, around Penrith, the Western Sydney airport, Parramatta, south-west Sydney, and the Illawarra…

Sydney Water said its wastewater systems at North Head, Malabar, and Bondi serviced 60% of customers but were “reaching capacity”.

New wastewater treatment plants would need to be built to service the growth regions.

Meanwhile, there are plans to diversify Sydney’s drinking water supply.

Warragamba Dam and the Prospect treatment plant supply drinking water for 80 per cent of Sydney Water customers.

Sydney Water said it was planning to build a new “rainfall-independent supply” including desalination and purified recycled water plants.

Professor Khan said it would cost “tens of billions of dollars” to ensure a resilient system capable of operating during extreme weather events…

“If we want all of these good outcomes of reliable drinking water and wastewater services then it is going to cost this type of money”, he said.

While technologies such as desalination and recycling can supplement water supplies, they are far more expensive than traditional water sources.

This means that home and business water prices will soar to accommodate high levels of immigration, which will disproportionately affect lower-income households.

Indeed, Infrastructure Australia’s 2017 modelling revealed that real household water expenditures would more than quadruple due to rapid population growth and climate change, rising from $1,226 in 2017 to $6,000 in 2067.

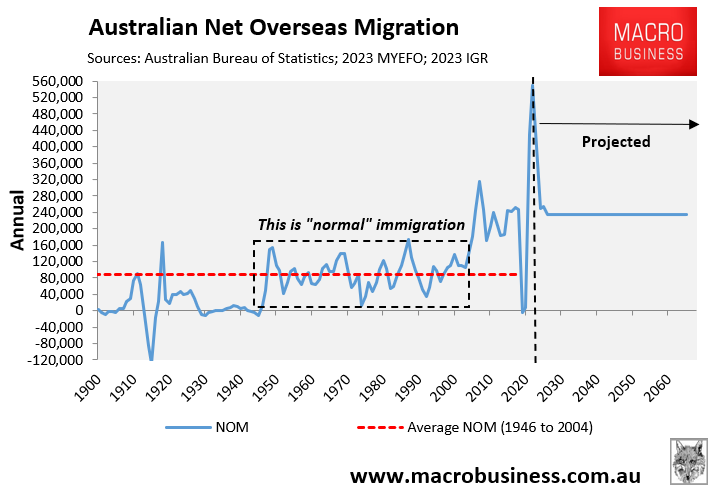

Sydney’s population has grown by around 1.4 million people (35%) since the Sydney Olympics, and it is projected to grow by another 3 million people over the next 50 years—all due to net overseas migration.

This population expansion will necessarily require a battery of expensive desalination plants to be built along Sydney’s coast.

Water is a prime example of why running a high immigration ‘Big Australia’ policy harms the living standards of the working class.