The Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) noted in the minutes of its board meeting for November that there are signs that the job market is beginning to tighten.

The unemployment rate was steady at 4.1% in October. RBA governor Michelle Bullock has previously indicated that the strength of the labour market is among the reasons why further interest rate increases could be on the agenda.

“A number of indicators – including measures of underemployment, youth unemployment, job advertisements and surveys of labour availability – suggested that the easing in the labour market might have begun to stall or modestly reverse”, the minutes read.

HSBC’s chief economist, Paul Bloxham, agrees with the RBA’s assessment that the labour market may not weaken further, which is likely to rule out an interest rate cut in the near term.

“The labour market looks like it might not be loosening further and might not continue to put downward pressure on inflation”, he said.

“That means the RBA won’t be able to cut interest rates soon, and may not be able to cut them all”.

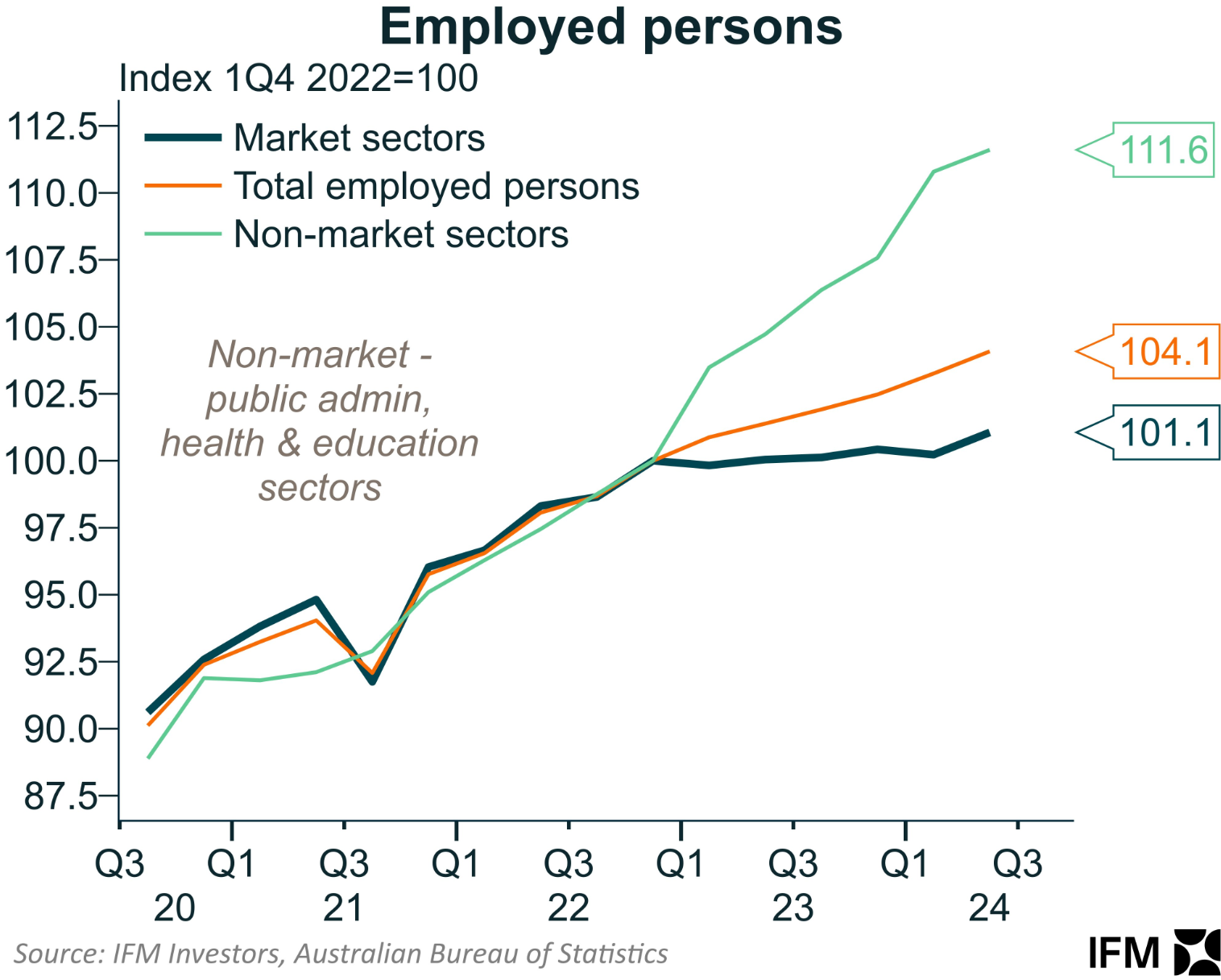

Most of the nation’s recent job growth has come from the non-market (government-aligned) sector, which includes private-sector employers reliant on public funding (e.g., private NDIS providers).

As illustrated below by Alex Joiner at IFM Investors, overall employment across the Australian economy grew by 4.1% between Q4 2022 and Q3 2024.

The non-market (government-aligned) sector expanded by an extraordinary 11.6%, compared to only 1.1% job growth across the market sector.

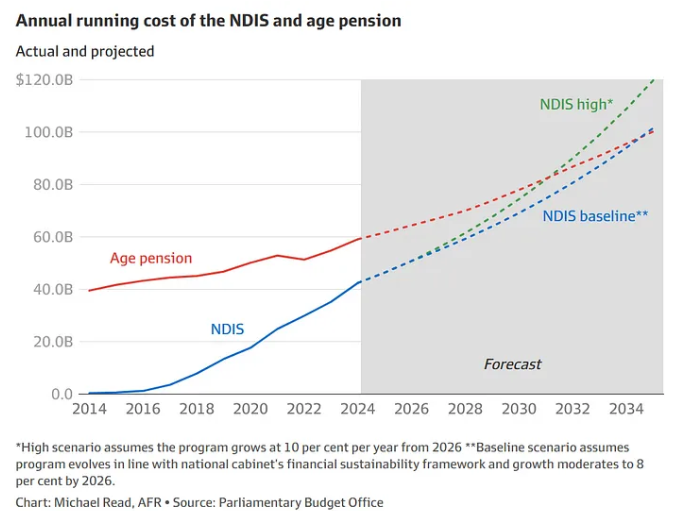

In a new report on Australia’s productivity, the Business Council of Australia (BCA) singled out the explosive growth in the NDIS as one of the significant drivers in government spending and falling productivity.

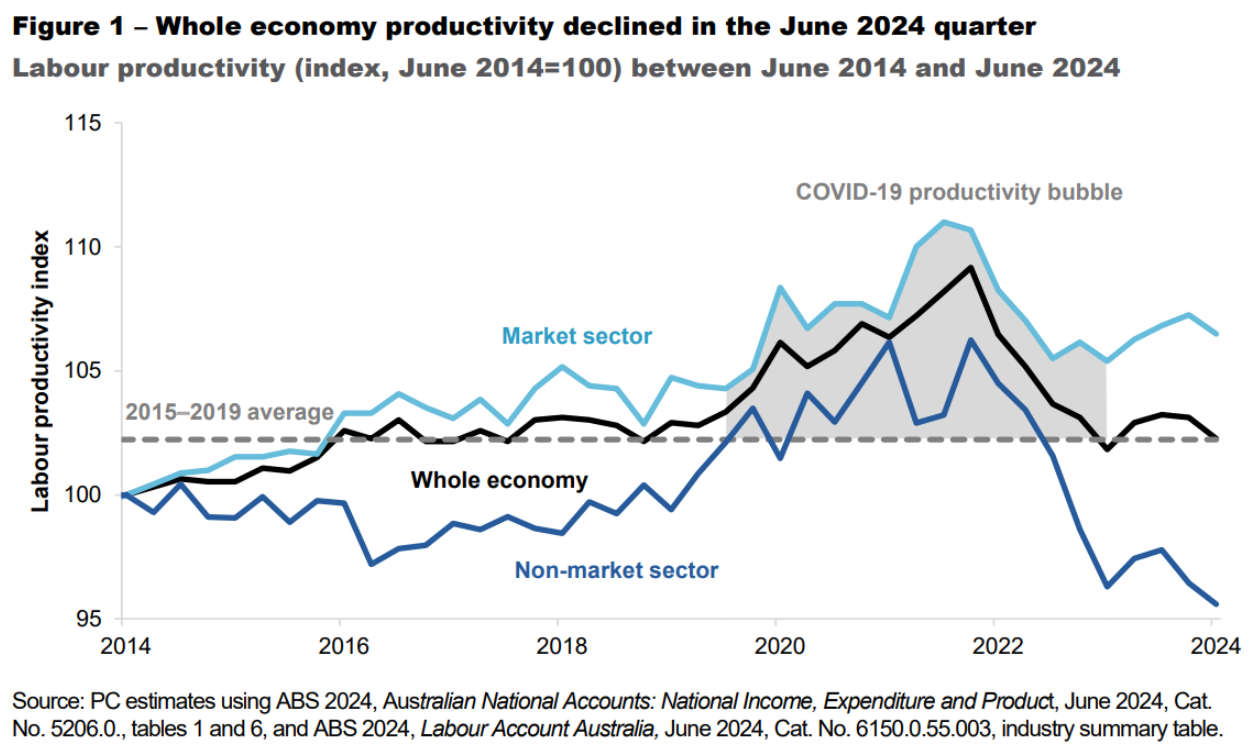

Jobs in the disability care sector have doubled since 2016, but the BCA claims that care economy jobs are far less productive than private sector positions.

The BCA also warns that productivity growth would need to accelerate to a 2% annual pace to meet the Australian Treasury’s long-run expectation of 1.2% productivity growth this decade.

“The past decade saw our living standards grow at their slowest rate since the Great Depression in the 1930s, and unless we turn it around, the next decade could be even worse”, BCA CEO Bran Black said.

AMP deputy chief economist Diana Mousina agreed that the explosive growth in non-market industries like healthcare and social assistance is behind the recent slump in productivity.

The data speaks for itself.

The Q2 national accounts revealed that Australia’s labour productivity (GDP per hour worked) fell to 2016 levels, driven by the non-market sector. This corresponded with the doubling of care jobs over the same period.

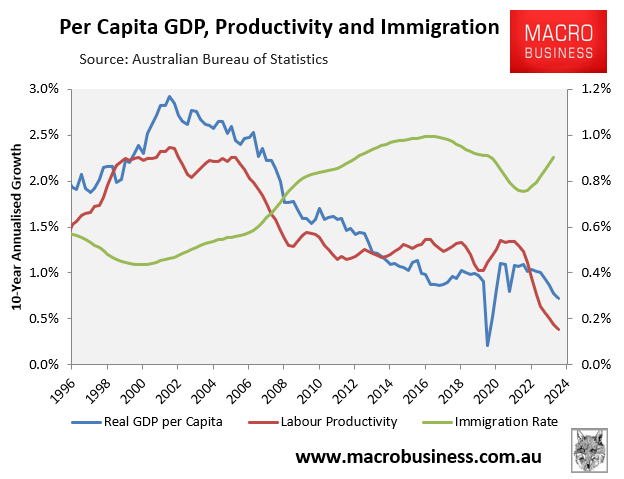

Australia’s longer-term productivity decline also corresponds with the structural increase in immigration in the mid-2000s.

The federal government more than doubled Australia’s net overseas migration, reducing productivity through what economists call “capital shallowing”.

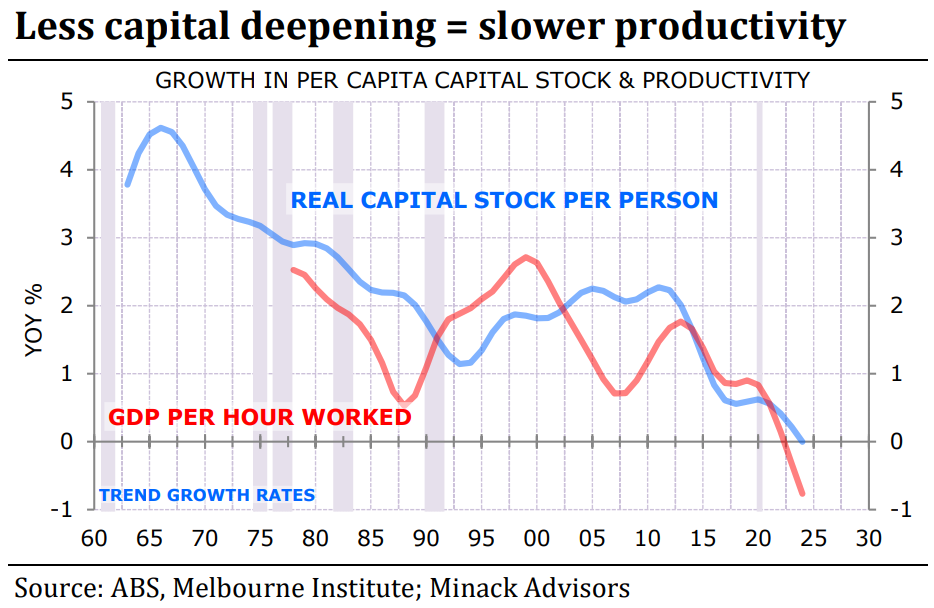

When a country’s population expansion outpaces its business, infrastructure, and housing investment, it produces less capital per worker, resulting in lower productivity and slower per capita growth.

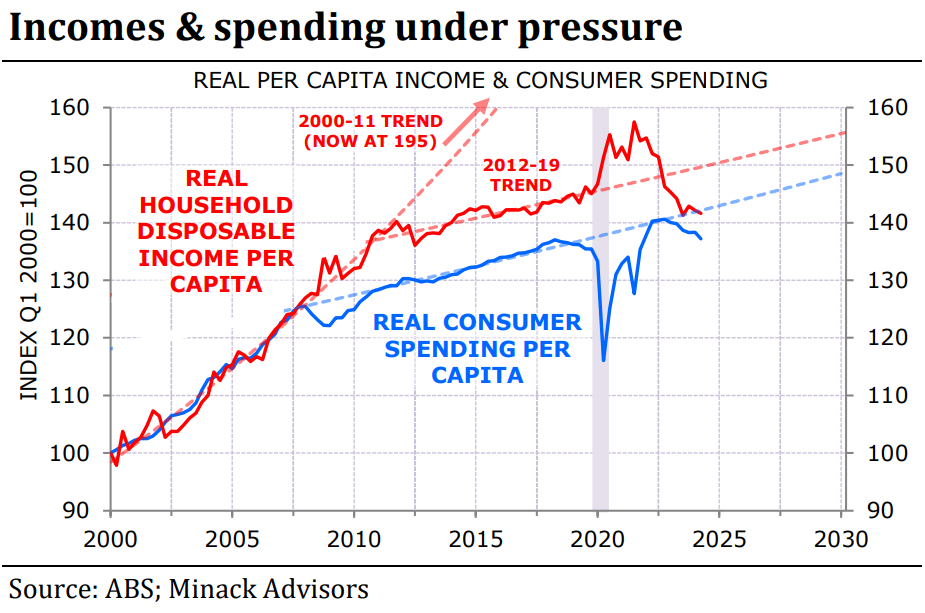

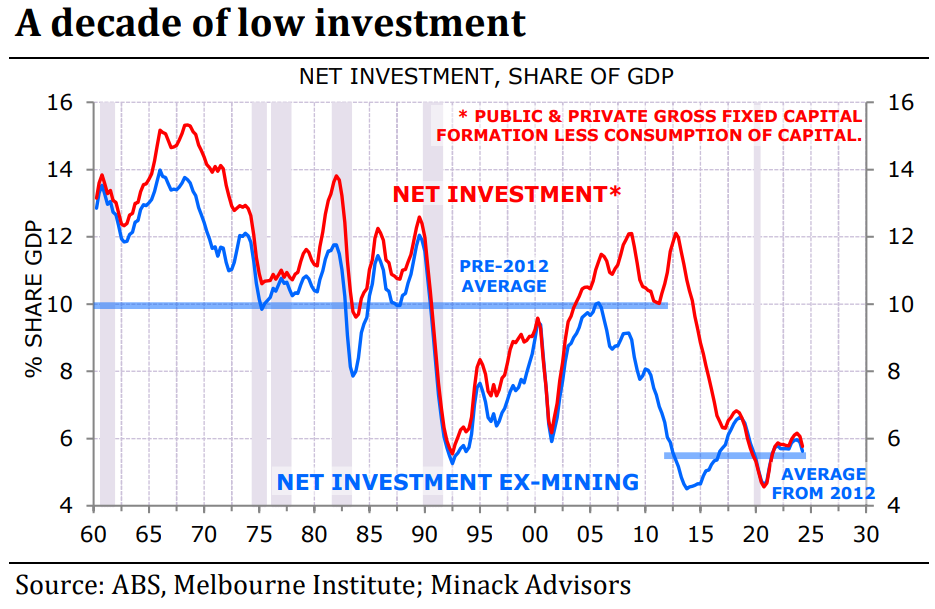

This month, independent economist Gerard Minack reported that “net investment spending (investment net of depreciation) is running at levels previously only seen at the nadir of the 1990s recession”.

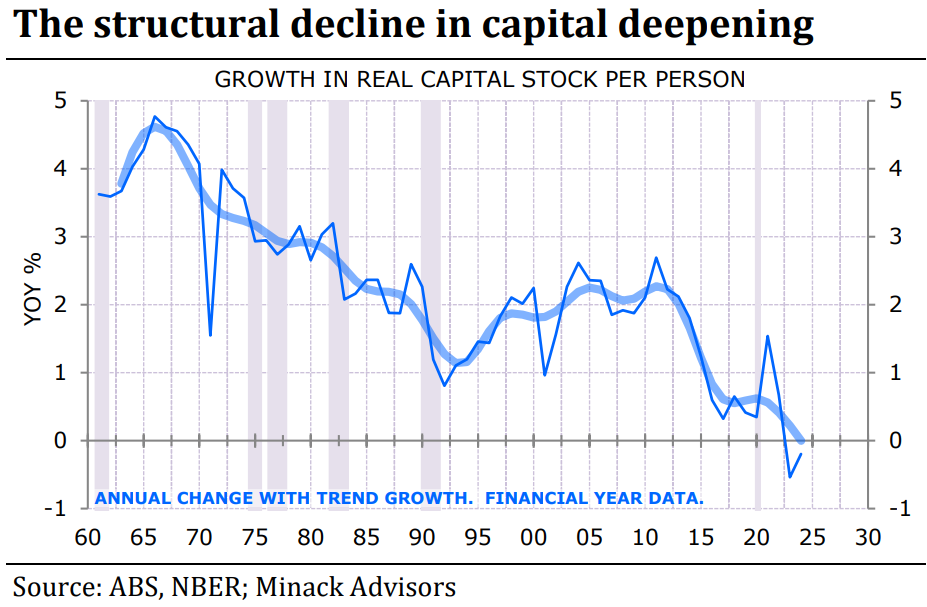

To compound matters, Minack demonstrated that “investment spending has been stretched thin by population growth”.

“The fast population growth of the past 20 years, combined with the decline in investment spending over the past decade, has led to a collapse in the growth of per capita capital stock”.

“Less deepening means less productivity growth”, Minack noted.

“Low investment and fast population growth is crushing productivity growth leading to structurally weak income growth”.

Australia is locked in a productivity trap since the federal government has committed to maintaining a high immigration rate indefinitely, which will necessarily result in more capital shallowing (or less capital deepening).

To make matters worse, the NDIS is expected to double in size over the coming decade, meaning that a higher share of the economy will be low-productivity caring jobs.

Without robust productivity growth, Australia will see modest economic and income growth in the 2030s.